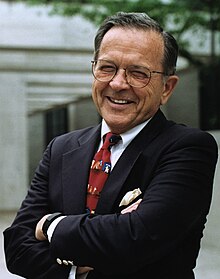

Charles A. Lockwood

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Ambiguitas atau ketaksaan[1] adalah satuan gramatikal dalam bentuk frasa atau kalimat yang bermakna ganda atau mendua arti yang terjadi sebagai akibat dari penafsiran struktur gramatikal yang berbeda. Dalam bahasa lisan penafsiran ganda ini tidak akan terjadi karena struktur gramatikal yang diucapkan akan dibantu oleh unsur intonasi.[2] Kata ambiguitas ini diserap dari bahasa Inggris yakni ambiguity yang berarti suatu konstruksi yang dapat ditafsirkan lebih dari satu arti.[...

ادمون أدولف دي روتشيلد (بالفرنسية: Edmond de Rothschild) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 30 سبتمبر 1926[1] باريس الوفاة 2 نوفمبر 1997 (71 سنة) [1] بريني شامبيزي [لغات أخرى][2] سبب الوفاة نفاخ رئوي[2] مواطنة فرنسا[2] عضو في مجموعة بلدربيرغ الزوج�...

Basilika Yesus Kekuatan MahabesarBasilika Minor Yesus Kekuatan MahabesarSpanyol: Basílica de Jesús del Gran PoderBasilika Yesus Kekuatan MahabesarLokasiSevillaNegara SpanyolDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaArsitekturStatusBasilika minorStatus fungsionalAktifAdministrasiKeuskupan AgungKeuskupan Agung Sevilla Basilika Yesus Kekuatan Mahabesar (Spanyol: Basílica de Jesús del Gran Poder) adalah sebuah gereja basilika minor Katolik yang terletak di Sevilla, Spanyol. Basilika ini ditet...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Coordination complex Octahedral molecular geometry is a common structural motif for homoleptic metal chloride complexes. Examples include MCl6 (M = Mo, W), [MCl6]− (M = Nb, Ta, Mo, W, Re), [MCl6]2- (M = Ti Zr, Hf, Mo, Mn, Re, Ir, Pd, Pt), and [MCl6]3- (M = Ru Os, Rh, Ir). In chemistry, a transition metal chloride complex is a coordination complex that consists of a transition metal coordinated to one or more chloride ligand. The class of complexes is extensive.[1] Bonding Halides ar...

Halaman ini berisi artikel tentang senator Amerika Serikat. Untuk musisi, lihat Ted Stevens (musisi). Ted Stevens Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (18 November 1923 – 9 Agustus 2010)[1][2][3] adalah seorang politikus Amerika Serikat yang menjabat sebagai Senator Amerika Serikat dari Alaska dari 1968 sampai 2009. Ia adalah Senat AS Partai Republik dengan masa jabatan terpanjang dalam sejarah pada masa ia meninggalkan jabatan; rekornya terlampaui pada Januari ...

Administrative region of Greece Administrative region in Aegean, GreeceSouth Aegean Περιφέρεια Νοτίου ΑιγαίουAdministrative region FlagCoordinates: 36°48′N 26°12′E / 36.8°N 26.2°E / 36.8; 26.2Country GreeceDecentralized AdministrationAegeanCapitalErmoupoliLargest cityRhodesRegional units List AndrosKalymnosKarpathos-KasosKea-KythnosKosMilosMykonosNaxosParosRhodesSyrosThiraTinos Government • Regional governorGiorgos Hatzim...

American doughnut shop chain This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Winchell's Donuts – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Winchell's Donut House, Inc.Winchell's Donut House in Los AngelesCompany typeSubsidiaryIndustryCoffeehouseGen...

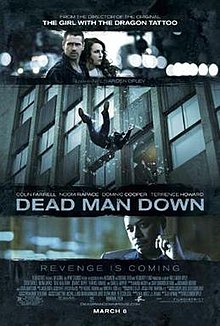

2013 American film by J.H. Wyman and Niels Arden Oplev Dead Man DownTheatrical release posterDirected byNiels Arden OplevWritten byJ.H. WymanProduced by Neal H. Moritz J.H. Wyman Starring Colin Farrell Noomi Rapace Dominic Cooper Terrence Howard Isabelle Huppert CinematographyPaul CameronEdited by Timothy A. Good Frédéric Thoraval Music byJacob GrothProductioncompanies Original Film Frequency Films IM Global WWE Studios Distributed byFilmDistrictRelease date March 8, 2013 (20...

هذه مقالة غير مراجعة. ينبغي أن يزال هذا القالب بعد أن يراجعها محرر؛ إذا لزم الأمر فيجب أن توسم المقالة بقوالب الصيانة المناسبة. يمكن أيضاً تقديم طلب لمراجعة المقالة في الصفحة المخصصة لذلك. (يوليو 2018) تحتوي هذه المقالة أبحاثًا أصيلةً، وهذا مُخَالفٌ لسياسات الموسوعة. فضلاً، أ...

Koridor 3 Trans SemarangPelabuhan - Elizabeth - PelabuhanArmada Bus Trans Semarang Koridor 3InfoPemilikBLU Trans SemarangWilayahKota SemarangJenisStreet-level Bus Rapid TransitJumlah stasiunLihat di Peta ruteOperasiDimulai1 November 2014Operator BLU Trans Semarang (prasarana dan petugas) PT Mekar Flamboyan Sendang Mulyo Jaya (armada dan pramudi) TeknisPanjang sistem40 kmKecepatan rata-rata50 km/jam Peta rute lbsTrans Semarang Koridor 3 Keterangan transit Pengapon: Raden Patah: Stasiun Tawang:...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع جورج باول (توضيح). هذه المقالة تحتاج للمزيد من الوصلات للمقالات الأخرى للمساعدة في ترابط مقالات الموسوعة. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة وصلات إلى المقالات المتعلقة بها الموجودة في النص الحالي. (يناير 2019) هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالا�...

Comune in Lombardy, ItalyLimone sul Garda LimùComuneComune di Limone sul GardaLocation of Limone sul Garda Limone sul GardaLocation of Limone sul Garda in ItalyShow map of ItalyLimone sul GardaLimone sul Garda (Lombardy)Show map of LombardyCoordinates: 45°48′30″N 10°47′15″E / 45.80833°N 10.78750°E / 45.80833; 10.78750[1]CountryItalyRegionLombardyProvinceBrescia (BS)Government • MayorAntonio MartinelliArea[2] • Total2...

Football stadium in London, England This article is about the stadium opened in 2007. For the original stadium which it replaced, see Wembley Stadium (1923). For the nearby indoor arena, see Wembley Arena. For the railway station, see Wembley Stadium railway station. Wembley StadiumThe Home of Football [1]New Wembley100th anniversary logo (2023)Exterior of the stadiumFull nameWembley Stadium connected by EELocationSouth WayWembleyHA9 0WSPublic transit Wembley Park Wembley Central Wemb...

Handwritten copy of a portion of the text of the Bible Part of a series on theBible Canons and books Tanakh Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim Old Testament (OT) New Testament (NT) Deuterocanon Antilegomena Chapters and verses Apocrypha Jewish OT NT Authorship and development Authorship Dating Hebrew canon Old Testament canon New Testament canon Composition of the Torah Mosaic authorship Pauline epistles Petrine epistles Johannine works Translations and manuscripts Dead Sea scrolls Masoretic Text Samarita...

English translation of the Septuagint Thomson translation of the Bible The Bible in English List of English Bible translations Old English (pre-1066) Middle English (1066–1500) Early Modern English (1500–1800) Modern Christian (1800– ) Modern Jewish (1853– ) Main category: Bible translations into English Bible portal vte Thomson's Translation of the Bible is a direct translation of the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament into English, rare for its time. It took Charles T...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando l'omonima emittente radiofonica svizzera, vedi Radio 24 (Svizzera). Radio 24Paese Italia Linguaitaliano Frequenzedi Radio 24 Data di lancio4 ottobre 1999 Share di ascolti2.192.000 (2º semestre 2023) EditoreGruppo 24 ORE MottoLa passione si sente Sito webwww.radio24.it/ DiffusioneTerrestreAnalogicoFM, in Italia DigitaleDAB, in Italia SatellitareHot Bird 13Bin chiaro freq. 12149pol. Vtransponder 72symbol rate 27500FEC 3/4 Sky ItaliaVideoGuard freq...

1990 greatest hits album by ABCAbsolutelyGreatest hits album by ABCReleased1990 (1990)GenreNew wavesynth-poppop rocksophisti-popblue-eyed soulLabelNeutronABC chronology Up(1989) Absolutely(1990) Abracadabra(1991) Singles from Abracadabra The Look of Love '90Released: 13 April 1990 Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllMusic[1]The Encyclopedia of Popular Music[2]Record Mirror[3]Robert Christgau[4]Smash Hits[5] Absolutely is a grea...

Штат БразилииЭспириту-Сантупорт. Espírito Santo Флаг Герб[вд] Anthem of Espírito Santo[вд] 20°19′08″ ю. ш. 40°20′16″ з. д.HGЯO Страна Бразилия Адм. центр Витория Губернатор Паулу Хартунг История и география Дата образования 1889 Площадь 46 098,6 км² (23-е место) Высота 756 м Часов�...

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: Western Beqaa District – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2023) District in Beqaa Governorate, LebanonWestern Beqaa District قضاء البقاع الغربيDistrictJoub JannineLocation in LebanonCountry LebanonGovernorateB...