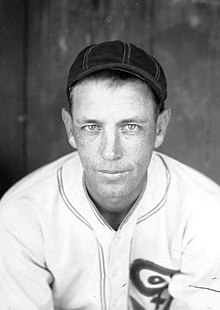

Ted Lyons

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Achmad Baidowi Anggota Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Republik IndonesiaPetahanaMulai menjabat 28 Juli 2016 PendahuluIvan HazPenggantiPetahanaWakil Sekretaris Jenderal Partai Persatuan PembangunanMasa jabatanMei 2016 – Januari 2021SekjenArsul Sani PenggantiQonita LutfiahIdy MuzayyadPengurus DPP PPP Bidang FungsionalPetahanaMulai menjabat Januari 2021Ketua UmumSuharso MonoarfaKetua Umum Generasi Muda Pembangunan IndonesiaPetahanaMulai menjabat 10 April 2021 PendahuluHilman Isma...

Erwin Sánchez Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Erwin Sánchez FrekingTanggal lahir 19 Oktober 1969 (umur 54)Tempat lahir Santa Cruz, BoliviaTinggi 1,74 m (5 ft 8+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain Gelandang serangKarier junior1981–1986 Tahuichi AcademyKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1987–1988 Destroyers 67 (23)1988–1990 Bolívar 34 (13)1990–1992 Benfica 15 (1)1991–1992 → Estoril (loan) 28 (8)1992–1997 Boavista 94 (21)1997–1998 Benfica 26 (6)1998–2004 Boavista...

Danau Jenewa Lac LémanCitra satelitLetak Swiss, PrancisKoordinat46°26′N 6°33′E / 46.433°N 6.550°E / 46.433; 6.550Koordinat: 46°26′N 6°33′E / 46.433°N 6.550°E / 46.433; 6.550Aliran masuk utamaRhone, La Venoge, Dranse, AubonneAliran keluar utamaRhoneWilayah tangkapan air7.975 km2 (3.079 mil persegi)Terletak di negaraSwiss, PrancisPanjang maksimal73 km (45 mi)Lebar maksimal14 km (8,7 mi)Area permukaan...

Railway station in Tamil Nadu, India Teni Indian Railways stationGeneral informationOther namesTeni railway stationLocationRailway Station Rd, Teni Allinagaram, Teni, Teni dt., Tamil NaduMadurai DivisionIndiaElevation348 metres (1,142 ft)Owned byIndian RailwaysOperated bySouthern RailwayLine(s)Madurai–Bodinayakkanur branch linePlatforms3Tracks3Train operatorsIndian RailwaysConstructionStructure typeStandard (on-ground station)ParkingYesAccessibleOther informationStatusOperationalStatio...

Ma On Shan skyline, formed by a mix of public and private housing estates. The following is a list of Public housing estates in Ma On Shan, Hong Kong, including Home Ownership Scheme (HOS), Private Sector Participation Scheme (PSPS), Sandwich Class Housing Scheme (SCHS), Flat-for-Sale Scheme (FFSS), and Tenants Purchase Scheme (TPS) estates. Overview Name Type Inaug. No Blocks No Units Notes Chevalier Garden 富安花園 PSPS 1987 17 3,942 Chung On Estate 頌安邨 Public 1996 5 2,834 Fu Fai...

Legislative Assembly of MontserratTypeTypeUnicameral HistoryFounded2011Preceded byLegislative CouncilLeadershipSpeakerCharliena White since 20 December 2020 PremierEaston Taylor-Farrell, MCAP since 19 November 2019 Leader of the OppositionPaul Lewis, PDM since 2019 StructureSeats9 seatsPolitical groupsHis Majesty's Government Movement for Change and Prosperity (5) His Majesty's Loyal Opposition People's Democratic Movement (3) Independent (1) Others Ex...

1969 Indian filmNil Gavani KaadhaliPosterDirected byC. V. RajendranWritten byChithralaya GopuStarringJaishankarBharathiCinematographyP. N. SundaramEdited byN. M. ShankarMusic byM. S. ViswanathanProductioncompanyReena FilmsRelease date 7 March 1969 (1969-03-07) Running time120 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageTamil Nil Gavani Kaadhali is a 1969 Indian Tamil-language crime thriller film, directed by C. V. Rajendran and written by Chithralaya Gopu. The film stars Jaishankar, Bharathi, ...

Questa voce sull'argomento allenatori di pallacanestro lituani è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Kazys Maksvytis Nazionalità Lituania Altezza 180 cm Peso 90 kg Pallacanestro Ruolo Allenatore Squadra Lituania CarrieraCarriera da allenatore 2008 Lituania U-162010 Lituania U-182010-2011 Aisčiai Kaunas2011 Lituania U-192011-2012 Sakalai Vilnius2012 Lituania U-202012-2015 Neptūnas Klaipėda2015-2017 Lietkabelis201...

Logo used since 2021 This is a list of local, regional, national and international television channels and radio stations owned by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in the United Kingdom and around the world. List of television channels In the UK, as well as on Freeview, satellite and cable services, the BBC's licence-funded television channels and their programmes can be watched live and on demand via BBC iPlayer. They can also be seen in Ireland and some parts of mainland Europe. ...

此條目可能包含不适用或被曲解的引用资料,部分内容的准确性无法被证實。 (2023年1月5日)请协助校核其中的错误以改善这篇条目。详情请参见条目的讨论页。 各国相关 主題列表 索引 国内生产总值 石油储量 国防预算 武装部队(军事) 官方语言 人口統計 人口密度 生育率 出生率 死亡率 自杀率 谋杀率 失业率 储蓄率 识字率 出口额 进口额 煤产量 发电量 监禁率 死刑 国债 ...

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. (September 2015) Click [show] for important translation instructions. View a machine-translated version of the Italian article. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wi...

نهائي كأس ملك إسبانيا 2017احتضن ملعب فيسنتي كالديرون بمدريد النهائيالحدثكأس ملك إسبانيا 2016–17 برشلونة ديبورتيفو ألافيس 3 1 التاريخ27 مايو 2017 (2017-05-27)الملعبفيسنتي كالديرون، مدريدالحكمكارلوس كلوس غوميزالحضور45.000[1] → 2016 2018 ← نهائي كأس ملك إسبانيا 2017 هي المباراة الن�...

1970 film by K. Balachander Kaviya ThalaiviTheatrical release posterDirected byK. BalachanderScreenplay byK. BalachandarBased onUttar Falguniby Nihar Ranjan GuptaProduced bySowcar JanakiStarringGemini GanesanSowcar JanakiCinematographyN. BalakrishnanEdited byN. R. KittuMusic byM. S. ViswanathanProductioncompanySelvi FilmsDistributed bySree Balaji MoviesRelease date 29 October 1970 (1970-October-29) Running time166 minutes[1]CountryIndiaLanguageTamil Kaviya Thalaivi (/k�...

Planar graph with 4 nodes and 5 edges Diamond graphVertices4Edges5Radius1Diameter2Girth3Automorphisms4 (Klein four-group: Z / 2 Z × Z / 2 Z ) {\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} /2\mathbb {Z} \times \mathbb {Z} /2\mathbb {Z} )} Chromatic number3Chromatic index3PropertiesHamiltonianPlanarUnit distanceTable of graphs and parameters In the mathematical field of graph theory, the diamond graph is a planar, undirected graph with 4 vertices and 5 edges.[1][2] It consist...

1654 battle part of Russo-Polish War Battle of SzepielewiczePart of Russo-Polish War (1654–67)The scheme of the battle near the village of Shepelevichi on August 14 (24), 1654 during the Russian-Polish war of 1654-1667 [1]Date24–25 August 1654LocationShepelevichy, present-day BelarusResult Russian victoryBelligerents Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Russian TsardomCommanders and leaders Janusz Radziwiłł Aleksey TrubetskoyStrength 6,000–8,000[2][3] 15,000[3&...

Malaysian politician (born 1962) In this Malay name, there is no surname or family name. The name Hamzah is a patronymic, and the person should be referred to by their given name, Amiruddin. The word bin or binti/binte means 'son of' or 'daughter of', respectively. Yang Berbahagia Dato' Wira Ir. HajiAmiruddin HamzahDGMK DSDK JPأميرالدين حمزةDeputy Minister of FinanceIn office2 July 2018 – 24 February 2020MonarchsMuhammad V (2018–2019) Abdullah (2019–2020)Pr...

Chronologies Crue de la Seine de 1910 par Carlo Brancaccio.Données clés 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913Décennies :1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940Siècles :XVIIIe XIXe XXe XXIe XXIIeMillénaires :-Ier Ier IIe IIIe Chronologies géographiques Afrique Afrique du Sud, Algérie, Angola, Bénin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroun, Cap-Vert, République centrafricaine, Comores, République du Congo, République démocrat...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Democratic Alignment Cyprus – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Greek. (October 2021) Click [...

Awlad Sidi Shaykhأولاد سيدي الشيخArab tribe in AlgeriaNotable of Awlad Sidi Shaykh in 1885EthnicityArabLocationWestern AlgeriaDescended fromSidi Shaykh (descendant of Abu Bakr)LanguageArabicReligionSunni Islam The Awlad Sidi Shaykh (Arabic: أولاد سيدي الشيخ, also spelled Ouled Sidi Cheikh) was a confederation of Arab tribes in the west and south of Algeria led by the descendants of the Sufi saint Sidi Shaykh. The Awlad had religious authority, and also owned agricu...

For the 1902 first Aswan dam, see Aswan Low Dam. Dam in Aswan, EgyptAswan High DamThe Aswan High Dam as seen from spaceLocation of the Aswan Dam in EgyptOfficial nameAswan High DamLocationAswan, EgyptCoordinates23°58′14″N 32°52′40″E / 23.97056°N 32.87778°E / 23.97056; 32.87778Construction began1960; 64 years ago (1960)Opening date1970; 54 years ago (1970)Owner(s)EgyptDam and spillwaysType of damEmbankm...