Susquehanna station

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

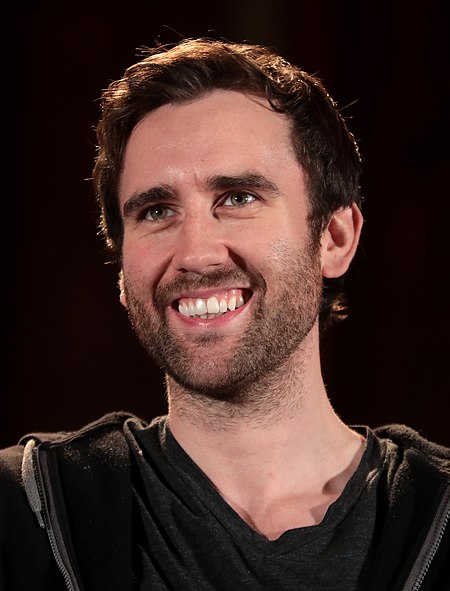

Matthew LewisLewis pada Mei 2019LahirMatthew David Lewis27 Juni 1989 (umur 34)Leeds, West Yorkshire, InggrisNama lainMatt LewisPekerjaan Aktor Tahun aktif1995–presentDikenal atasNeville Longbottom di Harry PotterSuami/istriAngela Jones (m. 2018)Situs webwww.matthewlewis.tv Matthew David Lewis (lahir 27 Juni 1989) adalah seorang aktor Inggris, yang cukup dikenal saat ia berperan sebagai Neville Longbottom dalam film Harry Potter. Biografi ...

Endomyxa Gromia brunneriTaksonomiSuperdomainBiotaSuperkerajaanEukaryotaKerajaanChromistaSubkerajaanHarosaInfrakerajaanRhizariaFilumCercozoaSubfilumEndomyxa Cavalier-Smith, 2002 Subkelompok Vampyrellida Phytomyxea Filoreta Gromia Ascetosporea lbs Endomyxa adalah sebuah kelompok dari organisme eukaryotik pada supergrup Rhizaria.[2][3][4] Awalnya kelompok ini dijadikan sebagai sebuah subfilum di Cerozoa, lalu belakangan sebagai subfilum Retaria. Namun, beberapa analisis m...

Italian prelate of the Catholic Church (born 1946) His EminenceMario ZenariCardinalApostolic Nuncio to SyriaZenari in 2022.ChurchRoman Catholic ChurchAppointed30 December 2008PredecessorGiovanni Battista MorandiniOther post(s)Cardinal-Deacon of Santa Maria delle Grazie alle Fornaci fuori Porta CavalleggeriOrdersOrdination5 July 1970by Giuseppe CarraroConsecration25 September 1999by Angelo SodanoCreated cardinal19 November 2016by Pope FrancisRankCardinal DeaconPersonal detailsBornMar...

Children's animated television series This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese Cat – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese CatBased onThe Chinese Siamese Cat by Amy TanDirect...

Program pelatihan adalah salah satu hal yang dikaji dalam psikologi industri Psikologi industri adalah ilmu yang mempelajari perilaku manusia di tempat kerja.[1] Ilmu ini berfokus pada pengambilan keputusan kelompok, semangat kerja karyawan, motivasi kerja, produktivitas, stres kerja, seleksi pegawai, strategi pemasaran, rancangan alat kerja, dan berbagai masalah lainnya.[1] Psikolog industri meneliti dan mengidentifikasi bagaimana perilaku dan sikap dapat diimprovisasi melalu...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Bola (disambiguasi). BolaTipeTabloid mingguan (1984–1997, 2013–2015)Tabloid dua kali seminggu (1997–2010, 2015–2018)Tabloid tiga kali seminggu (2010–2013)Harian (2013–2015)FormatTabloidPemilikKelompok Kompas GramediaPenerbitPT Tunas BOLADidirikan3 Maret 1984BahasaBahasa IndonesiaBerhenti publikasi26 Oktober 2018PusatPalmerah, Jakarta Barat, JakartaSurat kabar saudariKompasSitus web[1] Bola adalah tabloid olahraga Indonesia yang terbit enam kali dalam sem...

Overview of the national symbols of Portugal This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: National symbols of Portugal – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The symbols of Portugal are official and unofficial flags, icons or cultural express...

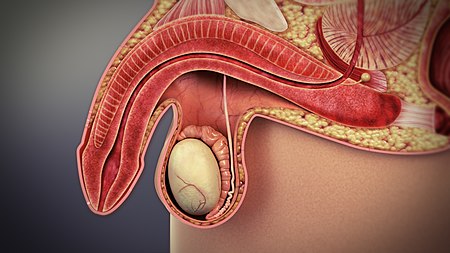

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Disfungsi ereksi – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTORUntuk kegunaan lain, lihat Penis. Disfungsi ereksiIlustrasi penampang melintang penis yang lembekInformasi umumNama lainImpotensiSpesia...

第三十二届夏季奥林匹克运动会柔道比賽比賽場館日本武道館日期2021年7月24日至31日項目數15参赛选手393(含未上场5人)位選手,來自128(含未上场4队)個國家和地區← 20162024 → 2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会柔道比赛个人男子女子60公斤级48公斤级66公斤级52公斤级73公斤级57公斤级81公斤级63公斤级90公斤级70公斤级100公斤级78公斤级100公斤以上级78公斤以上级团体混...

Family of gastropods Pleuroceridae Io fluvialis Athearnia anthonyi Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Mollusca Class: Gastropoda Subclass: Caenogastropoda Superfamily: Cerithioidea Family: PleuroceridaeFischer, 1885 Diversity[1][2] About 150 extant species Pleuroceridae, common name pleurocerids, is a family of small to medium-sized freshwater snails, aquatic gilled gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Cerithioidea.These snails have an operc...

Cortile d'onore di palazzo BreraLocalizzazioneStato Italia LocalitàMilano Indirizzovia Brera, 28 Coordinate45°28′19.2″N 9°11′16.43″E45°28′19.2″N, 9°11′16.43″E Informazioni generaliCondizioniIn uso CostruzioneXVII secolo RealizzazioneArchitettoFrancesco Maria Richini Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Il cortile d'onore del palazzo di Brera è il cortile principale del palazzo di Brera, sede dell'omonima pinacoteca e accademia. Indice 1 Storia e descrizione 1.1...

Simon LorenzLorenz in azione con il Bochum nel settembre 2019Nazionalità Germania Altezza187 cm Peso84 kg Calcio RuoloDifensore Squadra Ingolstadt 04 CarrieraGiovanili 200?-200? TSV Sulzbach200?-2009 SV Schefflenz2009-2016 Hoffenheim Squadre di club1 2016-2018 Hoffenheim II52 (7)2017-2018 Hoffenheim0 (0)2018 Bochum0 (0)2018-2019→ Monaco 186037 (3)2019-2020 Bochum16 (1)2020-2023 Holstein Kiel68 (3)[1]2023- Ingolstadt 0428 (1) 1 I du...

Football match2023 UEFA–CONMEBOL Club ChallengeThe Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán in Seville hosted the matchEventUEFA–CONMEBOL Club Challenge Sevilla Independiente del Valle 1 1 Sevilla won 4–1 on penaltiesDate19 July 2023VenueRamón Sánchez Pizjuán, SevilleRefereeRade Obrenović (Slovenia)[1]Attendance19,407[2]WeatherSunny36 °C (97 °F)[1]2024 → The 2023 UEFA–CONMEBOL Club Challenge (Spanish: UEFA–CONMEBOL Desafío de Clubes 2023), named Antoni...

Lokasi di Pennsylvania County Philadelphia adalah daerah terpadat di Pennsylvania dan daerah terpadat ke-24 di negara ini. Pada sensus 2020, county ini memiliki populasi 1.603.797 jiwa. Ibu kota countynya adalah Philadelphia, kota terbesar keenam di Amerika Serikat. County ini merupakan bagian dari wilayah negara bagian Pennsylvania Tenggara. Sejarah Suku Lenape asli Amerika adalah penghuni pertama yang diketahui di wilayah yang menjadi County Philadelphia. Pemukim Eropa pertama adalah orang...

Stasiun Shimotsuma下妻駅Stasiun Shimotsuma pada Juli 2008LokasiShimotsumaotsu 363-2, Shimotsuma-shi, Ibaraki-ken 304-0067JepangKoordinat36°10′56″N 139°57′54″E / 36.1822°N 139.9651°E / 36.1822; 139.9651OperatorKantō RailwayJalur■ Jalur JōsōLetak36.1 km dari TorideJumlah peron1 peron samping + 1 peron pulauInformasi lainStatusMemiliki stafSitus webSitus web resmiSejarahDibuka1 November 1913PenumpangFY20171734 Lokasi pada petaStasiun ShimotsumaLokasi d...

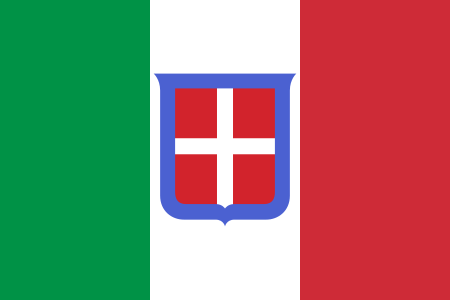

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Giardino. Gaetano Giardino Fonctions Ministre de la Guerre du royaume d'Italie 16 juin 1917 – 30 octobre 1917(4 mois et 14 jours) Monarque Victor-Emmanuel III Gouvernement Paolo Boselli Législature XXIVe Prédécesseur Paolo Morrone Successeur Vittorio Luigi Alfieri 21 juin 1917 – 21 novembre 1935(18 ans et 5 mois) Législature XXIVe, XXVe, XXVIe, XXVIIe, XXVIIIe et XXIXe Sénateur du royaume d'Italie Biographie Date de naissance 24 ...

CroisillescomuneCroisilles – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia Regione Normandia Dipartimento Orne ArrondissementArgentan CantoneVimoutiers TerritorioCoordinate48°46′N 0°16′E48°46′N, 0°16′E (Croisilles) Altitudine186 e 303 m s.l.m. Superficie11,27 km² Abitanti216[1] (2009) Densità19,17 ab./km² Altre informazioniCod. postale61230 Fuso orarioUTC+1 Codice INSEE61138 CartografiaCroisilles Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Croisilles ...

日本の政治家竹下 登たけした のぼる 内閣広報室より公表された肖像生年月日 1924年2月26日出生地 日本 島根県飯石郡掛合村(現・島根県雲南市)没年月日 (2000-06-19) 2000年6月19日(76歳没)死没地 日本 東京都港区(北里研究所病院)[1]出身校 早稲田大学商学部卒業前職 掛合中学校教員所属政党 自由民主党 (田中派) →(竹下派)称号 正二位 大勲位菊花大綬章�...

RF connector for coax cable BNC connector Male 50 ohm BNC connectorType RF coaxial connectorProduction historyDesigner Paul Neill, Carl ConcelmanDesigned 1940sManufacturer VariousGeneral specificationsDiameter Outer, typical: 0.570 in (14.5 mm), male 0.436 in (11.1 mm), female Cable CoaxialPassband Typically 0–4 GHz The BNC connector (initialism of Bayonet Neill–Concelman) is a miniature quick connect/disconnect radio frequency connector used for coaxial cable. It...

Dans ce nom, le nom de famille, Fan, précède le nom personnel Kuan. Fan KuanVoyageurs au milieu des Montagnes et des Ruisseaux (谿山行旅; encre et légère couleur sur soie[1]. 155,3 × 74,4 cm. Musée national du palais, Taipei[2].BiographieNaissance Яочжоу (d) (dynastie Song)Prénoms sociaux 中立, 仲立Activité PeintrePériode d'activité 990-1020Autres informationsMouvement Northern Landscape style (en)Genre artistique PaysageInfluencé par Li Cheng (en)modifier - mod...