State (printmaking)

|

Read other articles:

معتمدية أولاد حفوز تقسيم إداري البلد تونس[1] التقسيم الأعلى ولاية سيدي بوزيد رمز جيونيمز 11106666 تعديل مصدري - تعديل معتمدية أولاد حفوز إحدى معتمديات الجمهورية التونسية، تابعة لولاية سيدي بوزيد.[2] مراجع ^ صفحة معتمدية أولاد حفوز في GeoNames ID. GeoNames ID. ا...

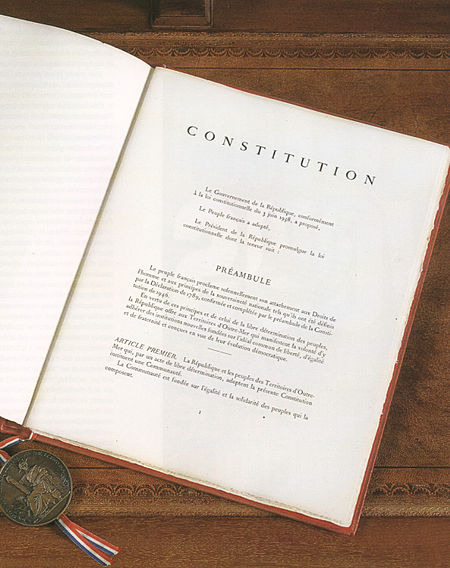

Cet article est une ébauche concernant le droit français. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Préambulede la Constitution de 1946 Données clés Présentation Titre préambule de la Constitution de la République française du 27 octobre 1946 Pays République française Langue(s) officielle(s) français Branche libertés et droits fondamentaux Adoption et entrée en vigueur Régime IVe ...

American magazine editor (born 1944) Terry McDonellMcDonell at Fortune Brainstorm TECH, July 2011Born (1944-08-01) August 1, 1944 (age 79)Norfolk, Virginia, United StatesOccupationMagazine editorChildrenNick McDonellThomas McDonellParentsRobert Meynard McDonell (father)Irma Sophronia Nelson (mother) Robert Terry McDonell (born August 1, 1944) is an American editor, writer and publishing executive.[1] He is a co-founder of the Literary Hub website that launched in 2015. His memoir...

Cinema ofBrazil List of Brazilian films Brazilian Animation Pre 1920 1920s 1930s 1930 1931 1932 1933 19341935 1936 1937 1938 1939 1940s 1940 1941 1942 1943 19441945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950s 1950 1951 1952 1953 19541955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960s 1960 1961 1962 1963 19641965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970s 1970 1971 1972 1973 19741975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980s 1980 1981 1982 1983 19841985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990s 1990 1991 1992 1993 19941995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000s 2000 2001 2002 2003 20042005 2...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (أكتوبر 2019) لويس دي لا بينيا معلومات شخصية الميلاد 23 يوليو 1931 (93 سنة)[1] مدينة مكسيكو الإقامة المكسيك مواطنة المكسيك الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم كلي...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Desember 2023. Yuichi SonodaInformasi pribadiNama lengkap Yuichi SonodaTanggal lahir 27 April 1975 (umur 48)Tempat lahir JepangPosisi bermain PenyerangKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1994-1995 Urawa Reds * Penampilan dan gol di klub senior hanya dihitung da...

Nat Turner ditangkap oleh Mr. Benjamin Phipps, seorang petani lokal Nat TurnerLahirNat (Turner)(1800-10-02)2 Oktober 1800Southampton County, VirginiaMeninggal11 November 1831(1831-11-11) (umur 31)Jerusalem, VirginiaSebab meninggalEksekusi hukum gantungKebangsaanAmerikaDikenal atasPemberontakan Nat TurnerSuami/istriCherry[1] Nat Turner (2 Oktober 1800 - 11 November 1831) adalah seorang budak Afrika-Amerika yang memimpin pemberontakan budak di Virginia pada 21 Agustus 1831 yan...

River in Victoria, AustraliaO'ShannassyLigar River East Branch, O'Shannassy River East Branch[1]O'Shannassy River CrossingLocation of the O'Shannassy River mouth in VictoriaEtymologyIn honour of John O'Shanassy [sic][2]LocationCountryAustraliaStateVictoriaRegionSouth Eastern Highlands (IBRA), Greater Metropolitan MelbourneLocal government areaYarra Ranges ShirePhysical characteristicsSourceYarra Ranges, Great Dividing Range • locationbelow Mo...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

Championnats du monde d'athlétisme 2003 Logo des championnats du monde d'athlétisme 2003.Généralités Sport Athlétisme Organisateur(s) IAAF Éditions 9e Lieu(x) Saint-Denis etParis, France Date 23 au 31 août 2003 Nations 198 Participants 1 679 Épreuves 46 Site(s) Stade de France Navigation 1983 • 1987 • 1991 • 1993 • 1995 • 1997 • 1999 • 2001 • 2003 • 2005 • 2007 • 2009 • 2011 • 2013 • 2015 • 2017 • 2019 • 2022 • 2023 • 2025 • 2027 modi...

American orchestral conductor This article is about the American orchestra conductor. For others with the same or similar name, see David Bernard (disambiguation). This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced ...

Political convention 1992 Democratic National Convention1992 presidential election NomineesClinton and GoreConventionDate(s)July 13–16, 1992CityNew York CityVenueMadison Square GardenKeynote speakerZell Miller, Barbara Jordan, and Bill BradleyCandidatesPresidential nomineeBill Clinton of ArkansasVice presidential nomineeAl Gore of TennesseeVotingTotal delegates4,288Votes needed for nomination2,145Results (president)Clinton (AR): 3,372 (78.64%)Brown (CA): 596 (13.90%)Tsongas (MA): 209 (4.87%...

一中同表,是台灣处理海峡两岸关系问题的一种主張,認為中华人民共和国與中華民國皆是“整個中國”的一部份,二者因為兩岸現狀,在各自领域有完整的管辖权,互不隶属,同时主張,二者合作便可以搁置对“整个中國”的主权的争议,共同承認雙方皆是中國的一部份,在此基礎上走向終極統一。最早是在2004年由台灣大學政治学教授張亞中所提出,希望兩岸由一中各表�...

Athletics at the1993 Summer UniversiadeTrack events100 mmenwomen200 mmenwomen400 mmenwomen800 mmenwomen1500 mmenwomen3000 mwomen5000 mmen10,000 mmenwomen100 m hurdleswomen110 m hurdlesmen400 m hurdlesmenwomen3000 msteeplechasemen4×100 m relaymenwomen4×400 m relaymenwomenRoad eventsMarathonmenwomen10 km walkwomen20 km walkmenField eventsHigh jumpmenwomenPole vaultmenLong jumpmenwomenTriple jumpmenwomenShot putmenwomenDiscus throwmenwomenHammer throwmenJavelin throwmenwomenCombined eventsHep...

American musician (born 1990) Brandon MillerBackground informationBorn (1990-04-08) April 8, 1990 (age 34)Gardner, Kansas, U.S.GenresBlues, Americana, rockOccupation(s)Musician, songwriter, performerInstrument(s)Guitar, mandolinYears active2005–presentWebsitebrandonmillerkc.comMusical artist Brandon Miller (born April 8, 1990) is an American singer-songwriter, guitarist. He was part of several cover bands in the Kansas City, Missouri area, would ultimately front the Brandon Miller Band...

Tasmanian International 1998Sport Tennis Data11 gennaio – 17 gennaio Edizione5a SuperficieCemento CampioniSingolare Patty Schnyder Doppio Virginia Ruano Pascual / Paola Suárez 1997 1999 Il Tasmanian International 1998 è stato un torneo di tennis giocato sul cemento. È stata la 5ª edizione del torneo, che fa parte della categoria Tier IV nell'ambito del WTA Tour 1998. Si è giocato al Hobart International Tennis Centre di Hobart in Australia, dall'11 al 17 gennaio 1998. Indice 1 Campione...

جريدة شمسمعلومات عامةالتأسيس ديسمبر 2005 القطع تابلويد الثمن 2 ر.س.موقع الويب shms.com.sa… شخصيات هامةالمالك تركي بن خالد بن فيصلالتحريراللغة اللغة العربيةالإدارةالمقر الرئيسي شارع محمد بن عبدالعزيز - التحلية بالرياض ، وفي جدة شارع محمد بن عبدالعزيز.- التحلية.الناشر تركي بن خال�...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع بون (توضيح). بون الإحداثيات 38°15′00″N 104°15′18″W / 38.25°N 104.255°W / 38.25; -104.255 [1] تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2][3] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة بويبلو خصائص جغرافية المساحة 0.961764 كيلومتر مربع0.961987 كيلومتر مربع (1...

Chemical reaction Rosenmund-von Braun reaction Named after Karl Wilhelm Rosenmund Julius von Braun Reaction type Substitution reaction Identifiers Organic Chemistry Portal rosenmund-von-braun-reaction RSC ontology ID RXNO:0000288 The Rosenmund–von Braun synthesis is an organic reaction in which an aryl halide reacts with cuprous cyanide to yield an aryl nitrile.[1][2][3] The reaction was named after Karl Wilhelm Rosenmund who together with his Ph.D. student Erich Str...