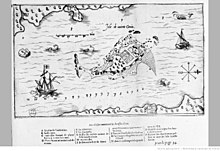

Saint Croix Island, Maine

| |||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Logo Miss World. Berikut merupakan pemegang titel Runner-Up kontes Miss World sejak edisi pertama kontes tahun 1951.[1][2] Pemegang titel Semenjak pelaksanaan Miss World 1951–1952, 1957, 1959–1965, 1967–1978, dan 1980 kontes ini telah menganugerahkan penghargaan kepada Top 5 berupa Miss World, Runner-Up 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Pada tahun 1954, 1966, 1981–2017 dan 2019–sekarang, kontes ini memberikan penghargaan Top 3 dengan penghargaan Miss World, Runner-Up 1, dan 2. Di sisi ...

Election in North Carolina Main article: 2020 United States presidential election 2020 United States presidential election in North Carolina ← 2016 November 3, 2020 2024 → Turnout77.4% Nominee Donald Trump Joe Biden Party Republican Democratic Home state Florida Delaware Running mate Mike Pence Kamala Harris Electoral vote 15 0 Popular vote 2,758,775 2,684,292 Percentage 49.93% 48.59% County Results Congressional District Results Precinct Resul...

Australian sprint canoeist Lyndsie FogartyPersonal informationBorn (1984-04-17) 17 April 1984 (age 39)Brisbane, QueenslandSportSportcanoe sprint Medal record Women's canoe sprint 2008 Beijing K-4 500 m Lyndsie Fogarty (born 17 April 1984 in Brisbane, Queensland) is an Australian sprint canoeist who has competed since the late 2000s. She won a bronze medal in at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing in the K-4 500 m event. References Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lyndsie Fogarty. A...

City in California, United States This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Paramount, California – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) City in California, United StatesParamount, CaliforniaCityLocation of Paramount in Los Ang...

I Gusti Nyoman Lempad Ramayana I Gusti Nyoman Lempad (Januari 1862 – 25 April 1978) adalah pelukis, pematung dan arsitek yang membangun istana dan pura di Ubud. Ia lahir di Bedahulu, Bali tahun 1862. Nyoman Lempad belajar melukis dari seorang Brahmin dan menjadi ahli dalam melukis. Kehidupan Lempad memiliki masa kecil yang lumayan sulit karena ia bersekolah di sekolah yang tidak formal sehingga ia tidak dapat membaca.[1] Hal yang bisa ia lakukan hanyalah mencontoh menu...

1962 film by Robert Stevenson In Search of the CastawaysTheatrical release posterDirected byRobert StevensonScreenplay byLowell S. HawleyBased onIn Search of the Castawaysby Jules VerneProduced byWalt DisneyStarringMaurice ChevalierHayley MillsGeorge SandersWilfrid Hyde-WhiteMichael Anderson Jr.Keith HamshereAntonio CifarielloCinematographyPaul BeesonEdited byGordon StoneMusic byMusic Composed by:Morton GouldAdditional Music by:Van CleaveMusical Director:Jack ShaindlinSongs:Richard M. Sherman...

England Template‑class England portalThis template is within the scope of WikiProject England, a collaborative effort to improve the coverage of England on Wikipedia. If you would like to participate, please visit the project page, where you can join the discussion and see a list of open tasks.EnglandWikipedia:WikiProject EnglandTemplate:WikiProject EnglandEngland-related articlesTemplateThis template does not require a rating on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. This template was consi...

Canadian television series This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (November 2020) This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all im...

SenilléfrazioneSenillé – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Francia RegioneAquitania-Limosino-Poitou-Charentes Dipartimento Vienne ArrondissementChâtellerault CantoneChâtellerault-3 ComuneSenillé-Saint-Sauveur TerritorioCoordinate46°46′N 0°36′E / 46.766667°N 0.6°E46.766667; 0.6 (Senillé)Coordinate: 46°46′N 0°36′E / 46.766667°N 0.6°E46.766667; 0.6 (Senillé) Superficie17,7 km² Abitanti690[1] (2009) Densità38,98 ab./km...

Skirt, HirariSingel oleh AKB48dari album Set List: Greatest Songs 2006–2007Sisi-BAozora no soba ni iteDirilis7 Juni 2006 (2006-06-07) (Indies)FormatCD SingelGenrePopDurasi18:19LabelAKSPenciptaYasushi Akimoto, Mio Okada, Yuichi YaegakiProduserYasushi Akimoto Skirt, Hirari (スカート、ひらりcode: ja is deprecated ) adalah singel kedua grup idola Jepang AKB48 yang dirilis secara independen oleh AKS, 7 Juni 2006.[1] Lagu ini dinyanyikan oleh 7 anggota dari Tim A AKB48, Tomom...

Spanish opera singer Isabella Colbran painted by Heinrich Schmidt Isabella Angela Colbran (2 February 1785 – 7 October 1845)[1] was a Spanish opera soprano and composer. She was known as the muse and first wife of composer Gioachino Rossini. Early years Colbran was born in Madrid, Spain, to Giovanni Colbran, King of Spain Carlos III's head court musician and violinist, and Teresa Ortola. She started her musical studies as a singer and composer at the age of six with composer and cel...

2004 single by Kanye West and Common For other uses, see Food (disambiguation). The FoodSingle by Common featuring Kanye West and DJ Dummyfrom the album Be ReleasedOctober 8, 2004Recorded2004; Sony Music Studios, New York, NY; The Dave Chappelle Show, New York, NYGenreHip hopconscious hip hopLength3:36LabelGOODGeffenSongwriter(s)Lonnie LynnKanye WestSam CookeEugene RecordStanley McKenneyProducer(s)Kanye WestCommon singles chronology Panthers (2002) The Food (2004) The Corner (2005) Kanye ...

Kimia polimer atau kimia makromolekular adalah ilmu multidisiplin yang berfokus pada sintesis kimia dan sifat kimia polimer dan makromolekul. Menurut rekomendasi IUPAC, makromolekul merujuk pada rantai molekul individu dan merupakan ranah ilmu kimia. Polimer menjelaskan sifat-sifat bahan polimer dan merupakan bidang fisika polimer sebagai subbidang dari fisika. Biopolimer yang diproduksi oleh organisme hidup: struktur protein: kolagen, keratin, elastin… fungsi kimia protein: enzim, hormon, ...

American screenwriter and director (born 1977) Dee ReesRees in 2012BornDiandrea Rees (1977-02-07) February 7, 1977 (age 47)Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.Alma materNew York UniversityFlorida A&M UniversityOccupationsFilm directorfilm producerscreenwriterYears active2005–presentSpouseSarah M. Broom Diandrea Rees[1] (born February 7, 1977) is an American screenwriter and director.[2][3][4] She is known for her feature films Pariah (2011), Bessie (...

Geologi strata di Salta (Argentina). Stratigrafi adalah studi mengenai sejarah, komposisi dan umur relatif serta distribusi perlapisan tanah dan interpretasi lapisan-lapisan batuan untuk menjelaskan sejarah Bumi. Dari hasil perbandingan atau korelasi antarlapisan yang berbeda dapat dikembangkan lebih lanjut studi mengenai litologi (litostratigrafi), kandungan fosil (biostratigrafi), dan umur relatif maupun absolutnya (kronostratigrafi). stratigrafi kita pelajari untuk mengetahui luas penyebar...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Boissieu. Famille de Boissieu Armes Blasonnement D'azur au chevron d'or, chargé à la pointe d'un trèfle d'azur Branches Déan de Luignédu Tiret Période XVIIe siècle - XXIe siècle Pays ou province d’origine Lyonnais Allégeance Royaume de France France libre France Demeures Château du Tiret (Ain)Château du Grand-BesseChâteaux de Mello Château de VarambonChâteau de Lavernette Charges Secrétaire de Marguerite de Valois, secr�...

Mula municipio de EspañaBanderaEscudo Vista de Mula y su vega. MulaUbicación de Mula en España MulaUbicación de Mula en la Región de Murcia País España• Com. autónoma Región de Murcia• Provincia Murcia• Comarca Comarca del Río Mula• Partido judicial MulaUbicación 38°02′31″N 1°29′26″O / 38.0418669, -1.4906872• Altitud 313 m(mín:?, máx: 1521)Superficie 633,38 ...

American philosopher Burton DrebenBornBurton Spencer Dreben(1927-09-27)September 27, 1927Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.DiedJuly 11, 1999(1999-07-11) (aged 71)Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.Era20th-century philosophyRegionWestern philosophySchoolAnalytic philosophyDoctoral advisorWillard Van Orman QuineDoctoral studentsCharles Parsons, T. M. ScanlonMain interestsMathematical logicHistory of analytic philosophy Burton Spencer Dreben (September 27, 1927 – July 11, 1999) was an American philo...

Nicholas Lea Nicholas Lea, nome d'arte di Nicholas Christopher Schroeder (New Westminster, 22 giugno 1962), è un attore canadese. Indice 1 Biografia 2 Filmografia 2.1 Cinema 2.2 Televisione 3 Doppiatori italiani 4 Altri progetti 5 Collegamenti esterni Biografia Lea è nato a New Westminster, in Columbia Britannica. Noto anche con il nome di Nicholas Christopher Herbert, per via del divorzio dei due genitori, dopo aver completato gli studi con laurea nel 1980 alla Prince of Wales Secondary Sc...

Monastero degli Arcangeli(Манастир Свети арханђели)Panorama generale del monastero degli Arcangeli.Stato// Kosovo[1] DistrettoPrizren LocalitàPrizren Coordinate42°12′01″N 20°45′45″E42°12′01″N, 20°45′45″E Religionecristiana ortodossa serba Diocesieparchia di Raška e Prizren ArchitettoMetropolitan Jacob Stile architettonicoromanico Inizio costruzione1343 Completamento1352 Sito webSito ufficiale Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Il...