Rotterdam Convention

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Harry WuWu pada sebuah konferensi pers di Washington D.C. pada Januari 2011Nama asal吴弘达Lahir(1937-02-08)8 Februari 1937Shanghai, TiongkokMeninggal26 April 2016(2016-04-26) (umur 79)HondurasWarga negaraAmerika SerikatSuami/istriChing LeeAnakHarrison Wu Harry Wu Hanzi tradisional: 吳弘達 Hanzi sederhana: 吴弘达 Alih aksara Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin: Wú Hóngdá Harry Wu (Hanzi: 吴弘达; Pinyin: Wú Hóngdá; 8 Februari 1937 – 26 April 2016) adalah...

Kambangan leher cincin Jantan Status konservasi Risiko Rendah (IUCN 3.1)[1] Klasifikasi ilmiah Domain: Eukaryota Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Chordata Kelas: Aves Ordo: Anseriformes Subordo: Anseres Superfamili: Anatoidea Famili: Anatidae Tribus: Aythyini Genus: Aythya Spesies: Aythya collarisDonovan, 1809 Peta persebaran Tempat pembiakan Persebaran sepanjang tahun Persebaran saat musim dingin K...

Šešupė Scheschuppe, ScheschupeSzeszuppe, Szeszupa, Suppe, Шешупе Daten Gewässerkennzahl RU: 01010000112104300007771 Lage Polen Polen Litauen Litauen Russland Russland Kaliningrad Oblast Oblast Kaliningrad Flusssystem Memel Quelle 14 km nordnordwestlich von Suwałki54° 13′ 16″ N, 22° 48′ 57″ O54.221184222.815954190 Quellhöhe ca. 190 m Mündung östlich Neman (Ragnit) in...

Politeknik Negeri Nusa UtaraJenisPerguruan Tinggi Negeri, PoliteknikDidirikan22 Juni 2011DirekturProf. Dr. Ir. Frans G. Ijong, M.Sc.AlamatJl. Kesehatan No.1, Kelurahan Sawang Bendar, Kecamatan Tahuna, Kabupaten Kepulauan Sangihe, Sulawesi Utara, IndonesiaSitus webhttps://www.polnustar.ac.id/ Politeknik Negeri Nusa Utara atau disingkat Polnustar adalah salah satu perguruan tinggi yang berada di Kabupaten Kepulauan Sangihe, Provinsi Sulawesi Utara. Nama kampus ini berasal dari Kepulauan Nusa Ut...

Alexandr KolobnevAlexandr Kolobnev en 2011.InformationsNom court Александр КолобневNaissance 4 mai 1981 (42 ans)VyksaNationalité russeSpécialité classiques[1]Équipes amateurs 2001San Pellegrino Sport-Bottoli-ArtoniÉquipes professionnelles 2002Acqua & Sapone-Cantina Tollo2003Domina Vacanze-Elitron2004Domina Vacanze2005-2006Rabobank01.2007-06.2008[n 1]CSC06.2008-12.2008[n 2]CSC Saxo Bank2009Saxo Bank2010-2011Katusha04.2012-12.2015[n 3]Katusha2016Gazprom-RusVeloPri...

Saori HaraHara di Festival Film Internasional Tokyo 2017Nama asal原 紗央莉LahirMai Kato1 Januari 1988 (umur 36)[1]Hiroshima, JepangTinggi165 m (541 ft 4 in)Situs webhttp://blog.livedoor.jp/harasaori/ Saori Hara (Jepang: 原 紗央莉code: ja is deprecated , Hepburn: Hara Saori, lahir 1 Januari 1988) adalah seorang mantan idola film dewasa, peraga busana dan pemeran asal Jepang yang memakai nama Mai Nanami (七海 まいcode: ja is deprecated , Nanami Mai)...

Half-Way HouseHalf-Way HouseHalf-Way HouseShow map of London Borough of EalingHalf-Way HouseShow map of Greater LondonFormer namesOld HatGeneral informationAddress142 Broadway, West Ealing, London,Town or cityLondonCountryEnglandCoordinates51°30′35″N 0°19′39″W / 51.5098°N 0.3275°W / 51.5098; -0.3275 The Half-Way House is a former inn at 142 Broadway, West Ealing, London, England. History The inn was originally known as the Old Hat, and was one of two by th...

New HampshireNegara bagian BenderaLambangPeta Amerika Serikat dengan ditandaiNegaraAmerika SerikatSebelum menjadi negara bagianProvince of New HampshireBergabung ke Serikat21 Juni 1788 (9)Kota terbesarManchesterPemerintahan • GubernurChris Sununu (R) • Wakil GubernurTidak ada[1] • Majelis tinggi{{{Upperhouse}}} • Majelis rendah{{{Lowerhouse}}}Senator ASJudd Gregg (R)Jeanne Shaheen (D)Delegasi DPR AS1: Carol Shea-Porter (D) 2: Paul Hodes ...

Battle in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine 2022 Kherson counteroffensivePart of the southern campaign of the Russian invasion of Ukraine A map showing the Kherson/Mykolaiv frontlineDate29 August – 11 November 2022(2 months, 1 week and 6 days)LocationSouthern Ukraine (Kherson and Mykolaiv oblasts)Result Ukrainian victory[3][4][5][6]Belligerents Ukraine Russia Donetsk PR[1][2] Luhansk PR[2]Commanders an...

San Marziale di Limoges Vescovo Venerato daChiesa cattolica Ricorrenza30 giugno Patrono diLimoges, Colle di Val d'Elsa; invocato contro le epidemie. Manuale Marziale di Limoges (Limoges, III secolo – ...) fu un vescovo missionario del III secolo, inviato da Roma a evangelizzare i Galli; è venerato come santo e confessore dalla Chiesa cattolica. Egli fa parte dei grandi santi di Gallia[1] con san Dionigi, san Privato, san Saturnino, san Martino di Tours, san Ferreolo di V...

1900年美國總統選舉 ← 1896 1900年11月6日 1904 → 447張選舉人票獲勝需224張選舉人票投票率73.2%[1] ▼ 6.1 % 获提名人 威廉·麥金利 威廉·詹寧斯·布賴恩 政党 共和黨 民主党 家鄉州 俄亥俄州 內布拉斯加州 竞选搭档 西奧多·羅斯福 阿德萊·史蒂文森一世 选举人票 292 155 胜出州/省 28 17 民選得票 7,228,864 6,370,932 得票率 51.6% 45.5% 總統選舉結果地圖,紅色代表�...

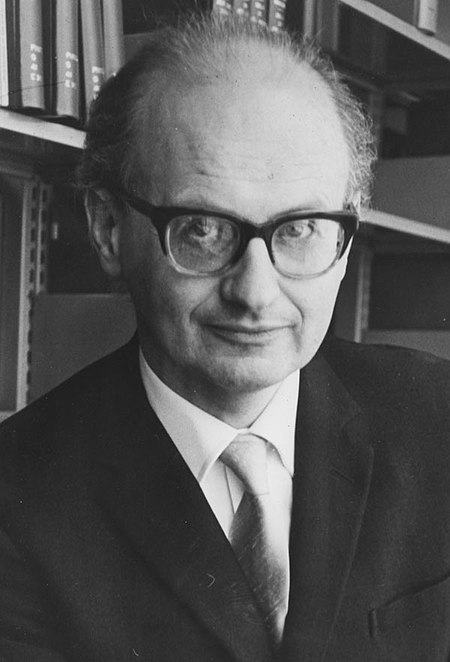

Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science For other people with the same name, see Lakatos (disambiguation). The native form of this personal name is Lakatos Imre. This article uses Western name order when mentioning individuals. Imre LakatosLakatos, c. 1960sBorn(1922-11-09)9 November 1922Debrecen, HungaryDied2 February 1974(1974-02-02) (aged 51)London, EnglandEducationUniversity of Debrecen (PhD, 1948)Moscow State UniversityUniversity of Cambridge (PhD, 1961)Era20th-century p...

Anders Tegnell Informasi pribadiLahirNils Anders Tegnell17 April 1956 (umur 68)Uppsala, SwediaKebangsaan SwediaAlma materUniversitas LundUniversitas LinköpingProfesiDokter,epidemiologis,pegawai negeriSunting kotak info • L • B Nils Anders Tegnell (lahir 17 April 1956)[1] adalah seorang dokter Swedia spesialis penyakit menular dan pegawai negeri.[2] Ia memainkan peran penting dalam gugus tugas Swedia terhadap pandemi flu babi 2009 dan pandemi COVID-19.&...

Subgroup of the Austronesian language family Not to be confused with Timor–Alor–Pantar languages. TimoricGeographicdistributionIndonesia East TimorLinguistic classificationAustronesianMalayo-PolynesianCentral–EasternTimoricProto-languageProto-TimoricSubdivisions(disputed) The Timoric languages are a group of Austronesian languages (belonging to the Central–Eastern subgroup) spoken on the islands of Timor, neighboring Wetar, and (depending on the classification) Southwest Maluku to the...

Museums in East Sussex, England This list of museums in East Sussex, England contains museums which are defined for this context as institutions (including nonprofit organizations, government entities, and private businesses) that collect and care for objects of cultural, artistic, scientific, or historical interest and make their collections or related exhibits available for public viewing. Also included are non-profit art galleries and university art galleries. Museums that exist only in cy...

Den här artikeln behöver källhänvisningar för att kunna verifieras. (2015-10) Åtgärda genom att lägga till pålitliga källor (gärna som fotnoter). Uppgifter utan källhänvisning kan ifrågasättas och tas bort utan att det behöver diskuteras på diskussionssidan. Cincinnati Stad Cincinnatis skyline. Flagga Sigill Etymologi: Stadens namn kommer från den romerske diktatorn Cincinnatus. Land USA Delstat Ohio Koordinater 39°N 84°V / 39°N 84°V / 39...

Este artículo o sección necesita referencias que aparezcan en una publicación acreditada. Busca fuentes: «Archiducado de Austria» – noticias · libros · académico · imágenesEste aviso fue puesto el 3 de agosto de 2013. Archiducado de AustriaErzherzogtum Österreich Estado imperial y tierra de la corona 1453-1804Bandera(1359-1804)Escudo(1359-1804) Las tierras de los Habsburgo en 1635; en rojo el archiducado de Austria, en azul las tierras de la Corona de Bohemia,...

Questa pagina è un archivio di passate discussioni. Per favore non modificare il testo in questa pagina. Se desideri avviare una nuova discussione o riprenderne una precedente già archiviata, è necessario farlo nella pagina di discussione corrente. Archivio3 Archivio5 Indice 1 Re: Stagioni Napoli C5 2 pasqua 3 Monitoraggio bandierine 4 Tony Mc Kenzie 5 Italia femminile C5 - Novità? 6 Benvenuto 7 Utente:Maxim1884 8 La tua pagina utente 9 Pagina Maximilian Nisi 10 Band. Perugia 11 Re:Stemm...

Governing body for cycling sport in Great Britain British CyclingSportCycle racingAbbreviationBCFounded1959AffiliationUCIRegional affiliationUECHeadquartersNational Cycling Centre, ManchesterPresidentBob HowdenCEOJon DuttonOfficial websitewww.britishcycling.org.uk British Cycling (formerly the British Cycling Federation) is the main national governing body for cycle sport in Great Britain. It administers most competitive cycling in Great Britain, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. It re...

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. The reason given is: DP&I Group has been restructed and is now known as Defence Strategic Policy and Industry Group, the Intelligence aspects have been moved under Defen...