Red culture movement

|

Read other articles:

120 anggota Knesset keenam terpilih pada 1 November 1965. Daftar anggota Anggota Yigal Allon Shulamit Aloni Moshe Aram Zalman Aran Moshe Baram Reuven Barkat Aharon Becker Mordechai Bibi Avraham Biton Moshe Carmel Gavriel Cohen Menachem Cohen Zvi Dinstein Abba Eban Aryeh Eliav Levi Eshkol Yosef Fischer Yisrael Galili Haim Gvati Akiva Govrin David Hacohen Ruth Haktin Asher Hassin Yisrael Kargman Kadish Luz Golda Meir Mordechai Namir Dvora Netzer Mordechai Ofer Baruch Osnia David Petel Dov Sadan...

American singer, actress, activist Etta Moten BarnettBorn(1901-11-05)November 5, 1901Weimar, Texas, U.S.DiedJanuary 2, 2004(2004-01-02) (aged 102)Chicago, Illinois, U.S.Occupation(s)Actress, singer, U.S. cultural representative in AfricaYears active1929–1952Spouses Curtis Brooks (m. c. 1918; div. 1924) Claude Albert Barnett (m. 1934; died 1967) Children3 Etta Moten Barnett (November 5, 1901 – January 2, 2004) was an A...

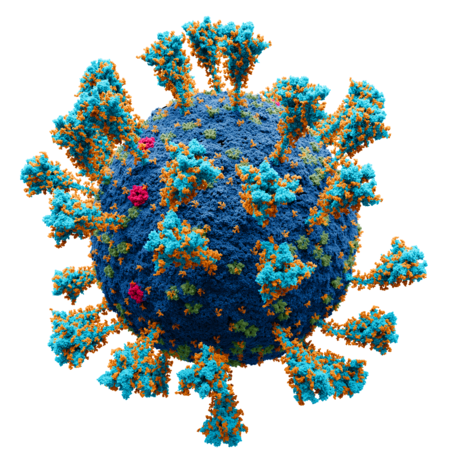

جائحة فيروس كورونا في الأردن كوفيد-19 في الأردن المرض مرض فيروس كورونا 2019 السلالة فيروس كورونا أول حالة 2 مارس 2020 التواريخ 4 سنوات، و1 شهر، و3 أسابيع، و4 أيام المنشأ ووهان عاصمة مقاطعة خوبي، الصين المكان الأردن الوفيات 4٬170 (19 يناير 2021)[1] الحالات المؤكدة 316�...

Australian politician The HonourableWilliam GilliesGillies in 192021st Premier of QueenslandIn office26 February 1925 – 22 October 1925GovernorMatthew NathanPreceded byTed TheodoreSucceeded byWilliam McCormackConstituencyEacham26th Treasurer of QueenslandIn office26 February 1925 – 22 October 1925Preceded byTed TheodoreSucceeded byWilliam McCormackConstituencyEachamMember of the Queensland Legislative Assemblyfor EachamIn office27 April 1912 – 24 Octob...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Oktober 2022. Michele TafoyaTafoya di tahun 2021LahirMichele Joan Tafoya17 Desember 1964 (umur 59)Manhattan Beach, California, U.S.AlmamaterUniversity of California, BerkeleyUniversity of Southern CaliforniaPekerjaanSportscasterTahun aktif1993–2022Suami/...

Historic railway in Ontario, Canada Several terms redirect here. For other uses, see Great Western Railway (disambiguation). Great Western RailwayThe Great Western Railway's Spitfire locomotive.OverviewHeadquartersHamilton, OntarioLocaleSouthwestern Ontario, Niagara PeninsulaDates of operation1853 (1853)–1882 (1882)TechnicalTrack gauge4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gaugePrevious gaugeBuilt to 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) but converted b...

Komando Resor Militer 073/MakutaramaLambang Korem 073/MakutaramaDibentuk1 September 1961Negara IndonesiaCabangTNI Angkatan DaratTipe unitKomando Resor MiliterPeranSatuan TeritorialBagian dariKodam IV/DiponegoroMakoremSalatigaJulukanKorem 073/MktPelindungTentara Nasional IndonesiaMotoBekti Tata Gapuraning BuwanaBaret H I J A U Situs webkorem073mkt.tni-ad.mil.idTokohKomandanKolonel Inf Purnomosidi, S.I.P., M.A.P.Kepala StafLetkol Kav Indarto Komando Resor Militer 073/Makutarama, disin...

Oberleichtersbach Lambang kebesaranLetak Oberleichtersbach di Bad Kissingen NegaraJermanNegara bagianBayernWilayahUnterfrankenKreisBad KissingenMunicipal assoc.Bad Brückenau Subdivisions5 OrtsteilePemerintahan • MayorWalter Müller (CSU/ Freie Christl. Wählergr.)Luas • Total27,60 km2 (1,070 sq mi)Ketinggian408 m (1,339 ft)Populasi (2013-12-31)[1] • Total2.046 • Kepadatan0,74/km2 (1,9/sq mi)Zona waktuW...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

Daimler L15 Role Light two seatsports aircraft/gliderType of aircraft National origin Germany Manufacturer Daimler Aircraft Company Designer Hans Klemm First flight 1919 Number built 1 The Daimler L15, sometimes later known as the Daimler-Klemm L15 or the Klemm-Daimler L15 was an early two-seat low-powered light aircraft intended to popularise flying. In mid-career it flew as a glider. Design and development The L15 in glider configuration L15 with revised undercarriage By the end of the Fir...

Airborne infantry regiment of the United States Army This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: 503rd Infantry Regiment United States – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment503rd Airborne Infantry Re...

Украинская держава, в дальнейшем — Украинская Народная Республика Западно-Украинская Народная Республика Эту страницу предлагается переименовать в «Отношения между УНР и ЗУНР».Пояснение причин и обсуждение — на странице Википедия:К переименованию/2 января 2018...

Osilo Ósile, Ósili, ÓsiluKomuneComune di OsiloLokasi Osilo di Provinsi SassariNegaraItaliaWilayah SardiniaProvinsiSassari (SS)Pemerintahan • Wali kotaGiovanni LigiosLuas • Total98,03 km2 (37,85 sq mi)Ketinggian672 m (2,205 ft)Populasi (2016) • Total3,059[1]Zona waktuUTC+1 (CET) • Musim panas (DST)UTC+2 (CEST)Kode pos07033Kode area telepon079Situs webhttp://www.comune.osilo.ss.it Osilo (bahasa Sardinia: Ó...

Scottish Labour politician Pam Duncan-GlancyMSPOfficial portrait, 2021Member of the Scottish Parliamentfor Glasgow(1 of 7 Regional MSPs)IncumbentAssumed office 6 May 2021Scottish Labour portfolios2021–2023Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Social Security2023–presentShadow Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills Personal detailsBorn (1981-11-02) 2 November 1981 (age 42)Political partyScottish LabourAlma materUniversity of StirlingGlasgow Caledonian University Pam Duncan-Glancy (born...

Not to be confused with Laurelton Hall. All-girls school in Milford, New Haven County, Connecticut, United StatesAcademy of Our Lady of Mercy, Lauralton HallAddress200 High StreetMilford, New Haven County, Connecticut 06460United StatesCoordinates41°13′23″N 73°03′54″W / 41.22300329526089°N 73.06486139896646°W / 41.22300329526089; -73.06486139896646InformationTypeAll-girlsMottoFides consequitur quodquonque petit(Faith attains all that it seeks)Religious affi...

Right for parents to have their children educated in accordance with their views Nineenth century allegorical statue of the Congress Column, Belgium depicting Freedom of Education Freedom of education is the right for parents to have their children educated in accordance with their religious and other views, allowing groups to be able to educate children without being impeded by the nation state. Freedom of education is a constitutional (legal) concept that has been included in the European C...

Ariel Universityאוניברסיטת אריאל בשומרוןTypePublicEstablished1982PresidentYehuda ShoenfeldRectorAlbert Pinhasov[1]Studentsapproximately 13,500 (as of August 2020)LocationAriel, Judea and Samaria Area[2]32°06′17″N 35°12′34″E / 32.10472°N 35.20944°E / 32.10472; 35.20944 BuildingBuilding details CampusurbanColorsTeal, navy and whiteAffiliationsIAUWebsiteEnglishHebrew Ariel University (Hebrew: אוניברסיטת �...

Powiat Starachowice Lambang Powiat Starachowice Lokasi Powiat Starachowice Informasi Negara Polandia Provinsi Święty Krzyż Ibu kota Starachowice Luas 523,41 km² Penduduk 91 780 (30 Juni 2016) Kadar urbanisasi 58,51 % Kode internasional (+48) 41 Pelat nomor kendaraan bermotor TST Pembagian administratif Kota 1 Kota kecamatan: 1 Kelurahan 3 Politik (Status: ) Bupati (Starost) Danuta Krępa Alamat ul. Władysława Borkowskiego 4 27-200 Starachowice Situs web resmi http://www.powia...

此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2013年2月5日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的标题(来源搜索:愛,川流不息 — 网页、新闻、书籍、学术、图像),以检查网络上是否存在该主题的更多可靠来源(判定指引)。 愛,川流不息类型真實人生劇場编剧劉肖蘭导演林博生主演參見演員列表制�...

Drop Dead FestivalDrop Dead Festival crowdGenrePunk rock, electronic, experimentalLocation(s)New York, New York and Europe[where?] with additional smaller events having formerly been held in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boston and New JerseyYears active2003-presentFoundersNY Decay ProductionsWebsitewww.dropdeadfestival.org The Drop Dead Festival is the largest DIY festival for art-damaged music. It has as many as 65 bands per event, and has been known to attract attendees from over 30 c...