Peggy Angus

| |||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Peta infrastruktur dan tata guna lahan di Komune Frain. = Kawasan perkotaan = Lahan subur = Padang rumput = Lahan pertanaman campuran = Hutan = Vegetasi perdu = Lahan basah = Anak sungaiFrain merupakan sebuah komune di departemen Vosges yang terletak pada sebelah timur laut Prancis. Lihat pula Komune di departemen Vosges Referensi INSEE Diarsipkan 2007-11-24 di Wayback Machine. lbsKomune di departemen Vosges Les Ableuvenettes Ahéville Aingevill...

Katedral Miranda do DouroKatedral Santa Maria MayorPortugis: Igreja Matriz de Mirandacode: pt is deprecated Katedral Miranda do DouroLokasiMiranda do DouroNegaraPortugalDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaArsitekturStatusKon-katedralStatus fungsionalAktifAdministrasiKeuskupanKeuskupan Bragança–Miranda Katedral Miranda do Douro (Portugis: Sé de Miranda do Dourocode: pt is deprecated , Mirandese: Sé de Miranda de l Douro) adalah sebuah gereja katedral Katolik yang terletak di Miranda do Douro...

Keith FooLahirFoo Chuan Chin6 Januari 1983 (umur 41)Sarawak, MalaysiaKebangsaanMalaysiaNama lainKeith FooPekerjaanAktor, ModelSuami/istriKim Raymond (m. 2015; c. 2019)Anak1 Keith Foo (lahir 6 Januari 1983) adalah pemeran film Indonesia yang berkewarganegaraan Malaysia. Beberapa judul film yang melibatkan dirinya di antaranya adalah Mati Suri (2009), Paku Kuntilanak, Bidadari Jakarta (2010), Pengantin Pantai Biru (2010) dan X - The...

لا يزال النص الموجود في هذه الصفحة في مرحلة الترجمة إلى العربية. إذا كنت تعرف اللغة المستعملة، لا تتردد في الترجمة. (أبريل 2019) سفير المغرب لدى المملكة المتحدة هو أعلى ممثل دبلوماسي للمملكة المغربية في المملكة المتحدة. منذ 1588م إلى 2009 انتدب المغرب 45 سفيرا لدى الدولة البريطاني�...

Peter HiggsHiggs pada April 2009LahirPeter Ware Higgs(1929-05-29)29 Mei 1929Newcastle upon Tyne, InggrisMeninggal8 April 2024(2024-04-08) (umur 94)Tempat tinggalEdinburgh, SkotlandiaKebangsaanInggrisAlmamaterKing's College LondonDikenal atasBroken symmetry pada Electroweak theoryHiggs bosonHiggs fieldHiggs mechanismPenghargaanNobel Prize in Physics (2013)Wolf Prize in Physics (2004)Sakurai Prize (2010)Dirac Medal (1997)Karier ilmiahBidangFisika teoriInstitusiUniversitas Edinburgh Imperi...

Sceaux 行政国 フランス地域圏 (Région) イル=ド=フランス地域圏県 (département) オー=ド=セーヌ県郡 (arrondissement) アントニー郡小郡 (canton) 小郡庁所在地INSEEコード 92071郵便番号 92330市長(任期) フィリップ・ローラン(2008年-2014年)自治体間連合 (fr) メトロポール・デュ・グラン・パリ人口動態人口 19,679人(2007年)人口密度 5466人/km2住民の呼称 Scéens地理座標 北緯48度4...

Jeanie MacPhersonLahirAbbie Jean Macpherson(1886-05-18)18 Mei 1886Boston, Massachusetts, A.S.Meninggal26 Agustus 1946(1946-08-26) (umur 60)Los Angeles, California, A.S.MakamHollywood Forever CemeteryPekerjaanAktris, screenwriter, sutradaraTahun aktif1908–1917 (akting)1913–1946 (screenwriting)Karya terkenalHer collaborations with director Cecil B. DeMille Abbie Jean MacPherson (18 Mei 1886 – 26 Agustus 1946)[1] adalah seorang aktris, penulis, dan sutradar...

1958 film The Beautiful Legs of SabrinaItalian theatrical release posterDirected byCamillo MastrocinqueWritten byEdoardo AntonMarcello FondatoVittorio MetzScreenplay byPiero PierottiStory byPiero PierottiStarringMamie Van DorenAntonio CifarielloRossana MartiniCinematographyAlvaro MancoriEdited byRoberto CinquiniMusic byLelio LuttazziProductioncompaniesPGC RomeCentral Cinema CompanyDistributed byStarlightRelease date November 21, 1958 (1958-11-21) (Italy) Running time109 min...

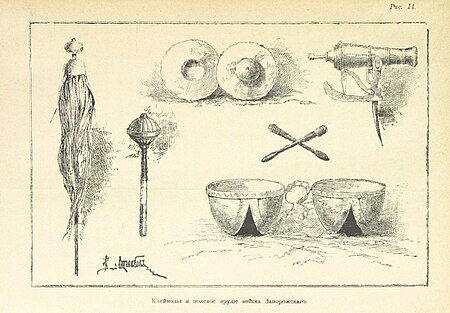

Військова музикаСтилістичні походження етнічна музикаПоходження фолк, класична музикаТипові інструменти мідні духові музичні інструменти, мембранофони, кларнет, глокеншпіль, бунчукПохідні жанри військовий індастріалСпоріднені жанри класична музикаРегіональні сце�...

Robert MullikenRobert Mulliken, Chicago 1929BiographieNaissance 7 juin 1896NewburyportDécès 31 octobre 1986 (à 90 ans)Comté d'ArlingtonNom dans la langue maternelle Robert Sanderson MullikenNationalité américaineFormation Université HarvardUniversité de ChicagoMassachusetts Institute of TechnologyActivités Physicien, chimiste théoricien, professeur d'universitéPère Samuel Parsons Mulliken (en)Autres informationsA travaillé pour Université d'État de FlorideUniversité de Ch...

Region of the state of Connecticut, U.S. For the planning region and council of governments, see Northwest Hills Planning Region, Connecticut. Western Connecticut Highlands and Greater Torrington redirect here. For the Connecticut wine region, see Western Connecticut Highlands AVA. For the town in Devon, England, see Great Torrington. Map of Connecticut showing the Northwest Connecticut region in green and the Litchfield Hills region in blue The Litchfield Hills (also known as the Northwest H...

Boulevard de Sébastopol Boulevard de Sébastopol adalah jalan raya penting di Paris, Prancis, yang berfungsi untuk membatasi arondisemen ke-1 dan ke-2 dari arondisemen ke-3 dan ke-4 kota. Boulevard ini memiliki panjang 1,3 km, dimulai dari place du Châtelet dan berakhir di boulevard Saint-Denis, kemudian menjadi Boulevard de Strasbourg. Boulevard adalah jalan raya utama, dan terdiri dari empat jalur kendaraan, salah satunya disediakan untuk bus. Meskipun jalan tersebut berjejer dengan beber...

American college football season 1897 Purdue Boilermakers footballConferenceWestern ConferenceRecord5–3–1 (1–2 Western)Head coachWilliam W. Church (1st season)CaptainWilliam S. MooreHome stadiumStuart FieldSeasons← 18961898 → 1897 Western Conference football standings vte Conf Overall Team W L T W L T Wisconsin $ 3 – 0 – 0 9 – 1 – 0 Chicago 3 – 1 – 0 11 – 1 – 0 Michigan 2 – ...

ويكيميديا كومنزالشعارمعلومات عامةموقع الويب commons.wikimedia.org (لغات متعددة) نوع الموقع القائمة ... مشروع محتوى من ويكيميديا — أرشيف — ويكي مع تحويل السكريبت — مشروع ويكيميديا — مكتبة الصور — منصة المحتوى التي أنشأها المستخدم التأسيس 7 سبتمبر 2004 الجوانب التقنيةاللغة لغات م�...

Overview of the high-speed rail system in the United States of America Map showing intercity passenger lines in the United States and their maximum speeds Amtrak Acela train at Old Saybrook, Connecticut Plans for high-speed rail in the United States date back to the High-Speed Ground Transportation Act of 1965. Various state and federal proposals have followed. Despite being one of the world's first countries to get high-speed trains (the Metroliner service in 1969), it failed to spread. Defi...

Halaman ini berisi artikel tentang lagu Amerika Serikat. Untuk lagu Italia tahun 1971, lihat Che sarà. Que Será, SeráDoris Day menyanyikan lagu ini dalam film The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956).Singel oleh Doris DayDirilis1956GenreMusik populer, SchlagerLabelColumbiaKomponis musikJay LivingstonLirikusRay Evans Que Será, Será (Whatever Will Be, Will Be), pertama kali dipublikasikan pada tahun 1956, adalah lagu yang ditulis oleh Jay Livingston dan Ray Evans. Lagu ini muncul pada film Alfred ...

Questa voce sull'argomento storici tedeschi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Georg Ludwig Voigt Georg Ludwig Voigt (Königsberg, 5 aprile 1827 – Lipsia, 18 agosto 1891) è stato uno storico e umanista tedesco. Professore dal 1861 al 1866 a Rostock e dal 1866 all'Università di Lipsia, fu il più significativo studioso dell'umanesimo italiano prima di Francesco de Sanctis e di Jacob Burckhardt. A lui, tra l'altro, si deve la coniazione...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento meteorologia è ritenuta da controllare. Motivo: voce in molti punti costituita da conclusioni originali basate su fonti giornalistiche Partecipa alla discussione e/o correggi la voce. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. La penisola italiana vista dal satellite in una giornata quasi ovunque serena del marzo 2003. È presente una copertura nuvolosa solo sulla Liguria e sulla Calabria tirrenica; sono visibili gli accumuli di neve sull'arc...

TRT WorldWhere News Inspires ChangeDiluncurkan18 Mei 2015 (siaran uji) 30 Juni 2015; 8 tahun lalu (2015-06-30)PemilikTurkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT)SloganWhere News Inspires Change.BahasaInggrisKantor pusatIstanbul, TurkiSitus webwww.trtworld.comTelevisi Internettrtworld.comLihat langsung TRT World adalah stasiun televisi berita internasional 24-jam berbahasa Inggris yang berbasis di Istanbul, Turki. Saluran ini menyediakan konten berita dan provides news and current affai...

Employment website JobServe Ltd.FormerlyFax-me LtdCompany typePrivate companyIndustryOnline Job-BoardFoundedAugust 1993, 23; 30 years ago (23-08-1993) in Tiptree, Essex, UKHeadquartersTiptree, Essex, UKArea servedEurope, Australia, North AmericaKey peopleRobbie Cowling, Co-founder and Managing DirectorParentAspire Media GroupWebsitewww.jobserve.com JobServe Ltd is a private company headquartered in Tiptree, Essex, United Kingdom, which runs an employment website, job adverts...