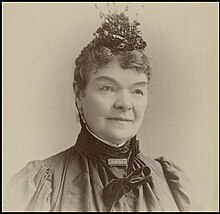

Mary Lee (suffragist)

| |||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

FereydunFreydun, ke-19Tokoh ShahnamehNamaFereydunGelarRajaAyahAbtinIbuFaranakAnak laki-lakiSalm, Tur, IrajCucuManuchehrMenteriSarv King of YemenOther InformationKematianAbedDikenal karenaKemerdekaan Iran dari Zahhak.Kesamaan historisEra Kassites Fereydun (Persia: فریدونcode: fa is deprecated ; Middle Persian: 𐭯𐭫𐭩𐭲𐭥𐭭, Frēdōn; Avestan: 𐬚𐬭𐬀𐬉𐬙𐬀𐬊𐬥𐬀, Θraētaona), atau Afrīdūn, adalah seorang raja Persia dan pahlawan dari Dinasti Pishdadian. Ia...

Ryan RossRyan Ross saat tampil bersama Panic! at the Disco di Honda Civic Tour di Houston pada tahun 2008.LahirGeorge Ryan Ross III30 Agustus 1986 (umur 37)Las Vegas, Nevada, Amerika SerikatPendidikan Bishop Gorman High School Universitas Nevada, Las Vegas Pekerjaan Penyanyi penulis lagu musisi Tahun aktif2004–2010; 2013–kiniKarier musikGenre Baroque pop pop rock rock psikedelik rock alternatif pop punk garage rock InstrumenVokal, gitarArtis terkait The Young Veins Panic! at th...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la télévision en Italie. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Rai Sport 2CaractéristiquesCréation 18 mai 2010Disparition 5 février 2017 : fusion entre la chaîne et Rai Sport 1.Propriétaire RaiLangue ItalienPays ItalieSite web http://www.raisport.rai.itDiffusionSatellite Sky Italia: chaîne n°228 Tivù Sat: chaîne n°23Câble naxoomodifier - modifie...

American politician, military official and author Amos J. PeasleeUnited States Ambassador to AustraliaIn officeAugust 12, 1953 – February 16, 1956PresidentDwight D. EisenhowerPreceded byPete JarmanSucceeded byDouglas M. Maffat Personal detailsBornMarch 24, 1887Clarksboro, New Jersey, U.S.DiedAugust 30, 1969 (aged 82)Manhattan, New York City, U.S.Alma materSwarthmore CollegeMilitary serviceAllegiance United StatesBranch/service United States Army United States NavyYe...

Voce principale: AGIL Volley. AGIL VolleyStagione 2014-2015L'AGIL Volley Sport pallavolo Squadra AGIL Allenatore Luciano Pedullà All. in seconda Daniele Adami Presidente Giovanna Saporiti Serie A11ª Play-off scudettoFinale Coppa ItaliaVincitrice Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Barun, Chirichella, Sansonna (32)Totale: Barun, Chirichella (43) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Barun (602)Totale: Barun (793) 2013-14 2015-16 Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti l'AGIL Volley nelle com...

Ann SothernSothern pada tahun 1960LahirHarriette Arlene Lake(1909-01-22)22 Januari 1909Valley City, Dakota Utara, Amerika SerikatMeninggal15 Maret 2001(2001-03-15) (umur 92)Ketchum, Idaho, Amerika SerikatSebab meninggalGagal jantungMakamKetchum CemeteryKebangsaanAmerika SerikatNama lainHarriet ByronHarriet LakePendidikanMinneapolis Central High SchoolAlmamaterUniversitas WashingtonPekerjaanPemeran, penyanyiTahun aktif1927–1987Suami/istriRoger Pryor &#...

Music festival founded by Eric Clapton For other uses, see Crossroads (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Crossroads Guitar Festival – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Crossroads Guitar FestivalEric Clapton a...

Marcos Acuña Acuña con la nazionale argentina al Mondiale 2022 Nazionalità Argentina Altezza 172 cm Peso 69 kg Calcio Ruolo Difensore, centrocampista Squadra Siviglia CarrieraGiovanili 2008-2011 Ferro Carril OesteSquadre di club1 2010-2014 Ferro Carril Oeste113 (5)2014-2017 Racing Club78 (16)2017-2020 Sporting Lisbona85 (7)2020- Siviglia98 (5)Nazionale 2016- Argentina56 (0)Palmarès Mondiali di calcio Oro Qatar 2022 Copa América Bronzo Bra...

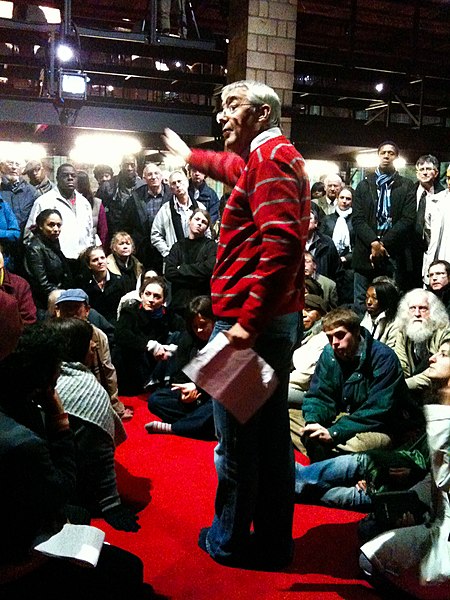

Birmingham Opera CompanyGraham Vick coaches the chorus during a rehearsalFormation1987 (1987)LocationBirmingham, EnglandDirectorGraham VickMusic DirectorAlpesh ChauhanWebsitewww.birminghamopera.org.uk Birmingham Opera Company is a professional opera company based in Birmingham, England, that specialises in innovative and avant-garde productions of the operatic repertoire, often in unusual venues.[1][2][3] History The company was founded by leading international o...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant l’Australie. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Chronologies Données clés 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015Décennies :1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040Siècles :XIXe XXe XXIe XXIIe XXIIIeMillénaires :Ier IIe IIIe Chronologies géographiques Afrique Afrique du Sud, Algérie, Angola, Bénin, ...

سفارة السلفادور في واشنطن العاصمة الإحداثيات 38°54′32″N 77°02′13″W / 38.9089°N 77.0369°W / 38.9089; -77.0369 البلد الولايات المتحدة المكان واشنطن العاصمة الاختصاص الولايات المتحدة الموقع الالكتروني الموقع الرسمي تعديل مصدري - تعديل سفارة السلفادور في وا...

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. Please help by editing the article to make improvements to the overall structure. (March 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. See Wikipedia's guide to w...

Radio station in Easton, PennsylvaniaWEEXEaston, PennsylvaniaBroadcast areaLehigh Valley (Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton)Frequency1230 kHzBrandingFox Sports Lehigh ValleyProgrammingFormatSportsAffiliationsFox Sports RadioLehigh Valley IronPigs Baseball Radio NetworkNew York Giants Radio NetworkNFL on Westwood One SportsOwnershipOwnerCumulus Media(Radio License Holding CBC, LLC)Sister stationsWCTO, WLEV, WODE-FM, WWYYHistoryFirst air dateMay 10, 1956 (1956-05-10)Former call signsWOD...

Sprint CanadaFormerlyCall-Net EnterprisesIndustryTelecommunicationsFounded1993; 31 years ago (1993)Defunct2005; 19 years ago (2005)FateAcquired and mergedSuccessorRogers TelecomArea servedCanadaServiceslandline, long-distance, dial-up Internet access, email, GSM (via Fido) Sprint Canada was a Canadian telecommunications service provider active from 1993 until 2005, when it was acquired by Rogers Communications. It offered both residential and business servi...

S.I.U.SutradaraHwang Byeng-gugProduserShin Beom-soo Kim Won-gukDitulis olehKim Yu-jin Hwang Seong-guPemeranUhm Tae-woong Joo WonPenata musikKim Tae-seong Noh Hyeong-wooSinematograferKang Seung-giPenyuntingMoon In-daeDistributorLotte EntertainmentTanggal rilis 24 November 2011 (2011-11-24) Durasi111 menitNegaraKorea SelatanBahasaKorea S.I.U. (Special Investigations Unit) (Hangul: 특수본; RR: Teuksubon) adalah film kejahatan laga Korea Selatan tahun 2011 yang...

Sporting event delegationTrinidad and Tobago at the2024 Summer OlympicsIOC codeTTONOCTrinidad and Tobago Olympic CommitteeWebsitewww.ttoc.orgin Paris, France26 July 2024 (2024-07-26) – 11 August 2024 (2024-08-11)Competitors18 in 3 sportsMedals Gold 0 Silver 0 Bronze 0 Total 0 Summer Olympics appearances (overview)19481952195619601964196819721976198019841988199219962000200420082012201620202024Other related appearances British West Indies (1960 S) Trini...

This article is about the Greek musician. For the auditory illusion, see Yanny or Laurel. For other uses, see Yanni (disambiguation). Greek musician, keyboardist, and composer YanniΓιάννης ΧρυσομάλληςYanni in 2007Background informationBirth nameYiannis Chryssomallis[1]Born (1954-11-14) November 14, 1954 (age 69)[2]Kalamata, GreeceGenresContemporary instrumental,[3] instrumental[3][4] crossover,[5] world, new-ageInstrument(...

Federal Highway AdministrationHistoireFondation 1966CadreSigle (en) FHWAType Agence fédérale des États-UnisSiège WashingtonPays États-UnisOrganisationOrganisation mère Département des Transports des États-UnisSite web (en) highways.dot.govmodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata La Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) est une agence du département des Transports des États-Unis responsable des autoroutes. Les principales activités de l'agence sont regroupées...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la Bresse et une commune de l’Ain. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Malafretaz Église Saint-Marc. Logo Administration Pays France Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Département Ain Arrondissement Bourg-en-Bresse Intercommunalité Communauté d'agglomération du Bassin de Bourg-en-Bresse Maire Mandat Gary Leroux 2020-2026 Code postal 01340 Code commune 01229 D...

Korean War Veterans Memorial IUCNカテゴリV(景観保護地域) 地域 アメリカ合衆国ワシントンD.C.座標 北緯38度53分16秒 西経77度2分50秒 / 北緯38.88778度 西経77.04722度 / 38.88778; -77.04722座標: 北緯38度53分16秒 西経77度2分50秒 / 北緯38.88778度 西経77.04722度 / 38.88778; -77.04722面積 8,900 m² (2.20 エーカー)創立日 1995年7月27日訪問者数 3,214,467人(2005年)運営組織...