Louis Alter

| |||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini bukan mengenai Penghargaan Akademi Televisi India.Indian Telly AwardsPenghargaan terkini: Indian Telly Awards 2019DeskripsiKeunggulan dalam TelevisiNegaraIndiaDiberikan perdana2001Situs webSitus Web ResmiSiaran televisi/radioSaluranStar Plus (2001–04)Sony TV (2005–09)Colors TV (2010–14)&TV (2015-18) ZEE5 (2019–sekarang)Indian Telly Awards adalah sebuah penghargaan tahunan yang diberikan untuk keunggulan dalam layar dan di belakang layar televisi India. Dikonsepkan dan ...

National anthem of Catalonia, Spain Els SegadorsEnglish: The ReapersNational anthem of CataloniaLyricsEmili Guanyavents, 1899MusicFrancesc Alió, 1892Adopted1993Audio sampleOfficial orchestral and choral vocal recording (sung in Standard Central Catalan)filehelp Instrumental recording of the anthem Els Segadors (Eastern Calatan: [əls səɣəˈðos], Western Calatan: [els seɣaˈðos]; The Reapers) is the official national anthem[1] of Catalonia, nationality...

Observatorium KerajaanNama alternatifRoyal Greenwich Observatory Kode observatorium 000 LokasiGreenwich, Royal Borough of Greenwich, Greenwich, Britania Raya Koordinat51°28′40″N 0°00′05″W / 51.47783°N 0.00139°W / 51.47783; -0.00139Koordinat: 51°28′40″N 0°00′05″W / 51.47783°N 0.00139°W / 51.47783; -0.00139Ketinggian68 m (223 ft) Didirikan1675 Situs webhttps://www.rmg.co.uk/royal-observatory/&#...

Untuk Ubud sebagai kawasan, lihat Ubud. UbudKecamatanPeta lokasi Kecamatan UbudNegara IndonesiaProvinsiBaliKabupatenGianyarPemerintahan • CamatDrs. I Kadek Alit Wirawan, M.A.P (2009)[1]Populasi • Total78,852 jiwa (2.014)[2] 69,323 jiwa (2.010)[3] jiwaKode pos80571Kode Kemendagri51.04.05 Kode BPS5104050 Luas42,38 Km²Desa/kelurahan7 Desa1 Kelurahan Kecamatan Ubud adalah sebuah kecamatan di Kabupaten Gianyar, Bali, Indonesia. Luasnya adalah 4...

Martin PBM Mariner Un PBM Mariner de l'United States Navy en vol en 1956. Constructeur Glenn L. Martin Company Rôle Hydravion de patrouille maritime/bombardier Statut Retiré du service Premier vol 18 février 1939 Mise en service Septembre 1940 Nombre construits 1 285 Équipage 7 membres Motorisation Moteur Wright R-2600-12 Cyclone 14 Nombre 2 Type 14 cylindres en double étoile Puissance unitaire 1 700 Dimensions Envergure 36 m Longueur 23,5 m Hauteur 5,33 m Surface alaire ...

سليمان كشك معلومات شخصية الميلاد 7 مايو 1994 (العمر 29 سنة)بنزرت، تونس الطول 1.82 م (5 قدم 11 1⁄2 بوصة) مركز اللعب ظهير أيسر الجنسية تونس معلومات النادي النادي الحالي الملعب التونسي المسيرة الاحترافية1 سنوات فريق م. (هـ.) 2011–2017 النادي الرياضي البنزرتي 75 (1) 2017–2018 النا...

K-Love radio station in Greenville, Mississippi, United States For the Charles City, Virginia radio station that held the call sign WLRJ at 89.7 FM from 2015 to 2017, see WRIQ. WLRJGreenville, MississippiBroadcast areaGreenville, MississippiFrequency104.7 MHzBrandingK-LOVEProgrammingFormatContemporary ChristianOwnershipOwnerEducational Media FoundationSister stationsWLRKHistoryFirst air date2005Former call signsWJIW (2003-2014)WIBT (2014-2017)WJIW (2017)Technical informationFacility ID43459Cl...

Dedah boh itik adalah masakan khas dari daerah Aceh Besar, provinsi Aceh. Makanan ini berupa olahan dadar telur bebek yang dicampur dengan kelapa parut dan bumbu rempah-rempah khas seperti, serai, temurui, daun jeruk, bawang merah, bawang putih, cabe rawit, kunyit, jahe, jeruk nipis dan garam.[1] Penyajian Salah satu keunikan dari makanan ini adalah pada proses pengolahan biasanya menggunakan wajan tanah liat yang diberi alas daun pisang sehingga menghasilkan aroma wangi yang khas. ...

This article is about the mountain range called Pindus. For other uses of these names, see Pindus (disambiguation). Pindos redirects here. For other uses, see Pindos (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Pindus – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2008) (Learn how ...

1930 film White CargoDirected byJ. B. WilliamsWritten byLeon Gordon (play) Ida Vera Simonton (novel)J. B. WilliamsProduced byArthur BarnesJ. B. WilliamsStarringLeslie FaberJohn F. HamiltonMaurice EvansCinematographyKarl PuthFreddie YoungProductioncompanyNeo-Art ProductionsDistributed byWilliams and Pritchard FilmsRelease datesMay 1930 (Premiere)October 1930 (General Release)Running time88 minutesCountryUnited KingdomLanguagesSound (Part-Talkie)English Intertitles White Cargo is a 1930 sound p...

Вое́нная грани́ца, или Вое́нная Кра́ина (нем. Militärgrenze; хорв. Vojna krajina, или Vojna granica; серб. Војна крајина / Vojna krajina, или Војна граница / Vojna granica; венг. katonai Határőrvidék) — пограничная область на юге Габсбургской монархии, прикрывавшая границу с Османской империей. Располагалась...

French film director and actor Robert GuédiguianGuédiguian at the 2015 Cannes Film FestivalBornRobert Jules Guédiguian (1953-12-03) 3 December 1953 (age 70)Marseille, FranceNationalityFranceOccupation(s)Film director, producer, screenwriter, actorYears active1980–presentSpouse Ariane Ascaride (m. 1975) Robert Jules Guédiguian (French: [ʁɔbɛʁ ɡediɡjɑ̃]; born 3 December 1953) is a French film director, screenwriter, producer and act...

Script used for Old South Arabian languages This article's lead section contains information that is not included elsewhere in the article. If the information is appropriate for the lead of the article, this information should also be included in the body of the article. (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Ancient South Arabian scriptScript type Abjad Time periodLate 2nd millennium BCE to 6th century CEDirectionRight-to-left script LanguagesOld South Arabian, Ge'ezRe...

Close, long-term biological interaction between distinct organisms (usually species) This article is about the biological phenomenon. For other uses, see Symbiosis (disambiguation). In a cleaning symbiosis, the clownfish feeds on small invertebrates, that otherwise have potential to harm the sea anemone, and the fecal matter from the clownfish provides nutrients to the sea anemone. The clownfish is protected from predators by the anemone's stinging cells, to which the clownfish is immune. The...

Espionage arm of the US Defense Intelligence Agency Not to be confused with National Clandestine Service. Defense Clandestine ServiceAgency overviewPreceding AgencyDefense Human Intelligence ServiceJurisdictionFederal government of the United StatesHeadquartersDefense Intelligence Agency HeadquartersEmployeesc. 500[1]Agency executiveScott D. Berrier[2], Director of the Defense Intelligence AgencyParent AgencyDefense Intelligence AgencyWebsitewww.dia.mil The Defense Clandestine...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento armi da fuoco è priva o carente di note e riferimenti bibliografici puntuali. Commento: Note rarefatte, gran parte della voce non è referenziata e, quindi, è inaffidabile. Sebbene vi siano una bibliografia e/o dei collegamenti esterni, manca la contestualizzazione delle fonti con note a piè di pagina o altri riferimenti precisi che indichino puntualmente la provenienza delle informazioni. Puoi migliorare questa voce citando le fonti più precisam...

DownerCanberra, Australian Capital TerritoryDowner shops in 2022DownerCoordinates35°14′39″S 149°08′42″E / 35.24417°S 149.14500°E / -35.24417; 149.14500Population4,296 (SAL 2021)[1]Established1960Postcode(s)2602Area1.6 km2 (0.6 sq mi)DistrictNorth CanberraTerritory electorate(s)KurrajongFederal division(s)Canberra Suburbs around Downer: Lyneham Mitchell Watson Lyneham Downer Hackett Lyneham Dickson Hackett Downer is a suburb of C...

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: Friedrich Claus – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2021) German association football player Friedrich ClausPersonal informationDate of birth (1890-03-18)18 March 1890Place of birth Frankfurt, GermanyDate of death 16 May 1962(1962-0...

English landowner and Whig politician Thomas de Grey (1680 – 1765) of Merton, Norfolk, was an English landowner and Whig politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1708 and 1727. Early life Merton Hall, Norfolk De Grey was baptised on 13 August 1680, the eldest surviving son of William de Grey and his wife Elizabeth Bedingfield, daughter of Thomas Bedingfield of Darsham.[1] He was educated at Bury St Edmunds Grammar School and was admitted at St John's College, Cambridge on ...

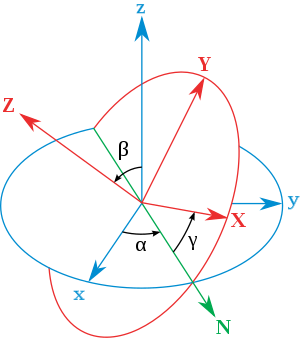

Description of the orientation of a rigid body Classic Euler angles geometrical definition. Fixed coordinate system (x, y, z) Rotated coordinate system (X, Y, Z) Line of nodes (N) The Euler angles are three angles introduced by Leonhard Euler to describe the orientation of a rigid body with respect to a fixed coordinate system.[1] They can also represent the orientation of a mobile frame of reference in physics or the orientation of a general basis ...