Kosovo Protection Corps

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Bhagwan Das Garga, yang juga dikenal sebagai B. D. Garga (14 November 1924 di Lehragaga, Punjab[1] - 18 Juli 2011 di Patiala, Punjab), adalah seorang pembuat film dokumenter dan sejarawan film India. B.D. Garga meninggal pada 18 Juli 2011 di Patiala, Punjab. Sekuel untuk Silent Cinema in India, sebuah buku berjudul, The Sunshine Years, tentang sejarah film bersuara dan sistem studio di India, adalah sebuah karya yang belum diselesaikan. Filmografi 1948: Storm over Kashmir 1960: Family...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento Veneto è priva o carente di note e riferimenti bibliografici puntuali. Sebbene vi siano una bibliografia e/o dei collegamenti esterni, manca la contestualizzazione delle fonti con note a piè di pagina o altri riferimenti precisi che indichino puntualmente la provenienza delle informazioni. Puoi migliorare questa voce citando le fonti più precisamente. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. San Bonifaciocomune San Bonifacio – VedutaPia...

Football cup tournament final for AIFF Football match2024 Super Cup finalKalinga Stadium hosted the matchEvent2024 Super Cup East Bengal Odisha 3 2 After Extra TimeDate28 January 2024VenueKalinga Stadium, BhubaneswarPlayer of the MatchSaúl Crespo (East Bengal)[1]RefereeVenkatesh R.Attendance10,121WeatherWarm and humid← 2023 2025 → The 2024 Super Cup final was the final match of the 2024 Super Cup, the fourth edition of the Super Cup. It was played at Kalinga Stadium in Bh...

American historian, writer, and environmentalist Wallace StegnerStegner c. 1969BornWallace Earle Stegner(1909-02-18)February 18, 1909Lake Mills, Iowa, U.S.DiedApril 13, 1993(1993-04-13) (aged 84)Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.Occupation Historian novelist short story writer environmentalist EducationUniversity of Utah (BA)University of Iowa (MA, PhD)Period1937–1993Notable awardsPulitzer Prize for Fiction(1972, Angle of Repose)National Book Award for Fiction(1977, The Spectator Bird)Sp...

la Loise La Loise à Feurs,ancienne capitale historique du Forez. Caractéristiques Longueur 24,9 km [sandre 1] Bassin 146 km2 [sandre 1] Bassin collecteur la Loire Débit moyen 0,714 m3/s (Feurs) [1] Nombre de Strahler 4 Organisme gestionnaire EPTB Loire Régime pluvial océanique Cours Source au lieu-dit l'Étang · Localisation Villechenève · Altitude 710 m · Coordonnées 45° 48′ 50″ N, 4° 23′ 19″ E Confluence la Loire · Loca...

Singaporean politician Ong Chit Chung翁执中Member of the Singapore Parliamentfor Jurong GRC (Bukit Batok)In office25 October 2001 – 14 July 2008Preceded byPosition establishedSucceeded byDavid OngMember of the Singapore Parliamentfor Bukit Timah GRC (Bukit Batok)In office2 January 1997 – 18 October 2001Preceded byPosition establishedSucceeded byPosition abolishedMember of the Singapore Parliamentfor Bukit BatokIn office3 September 1988 – 16 December 1996Pre...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant une localité flamande. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Niel-bij-As Église Saint-Nicolas Administration Pays Belgique Région Région flamande Communauté Communauté flamande Province Province de Limbourg Arrondissement Hasselt Commune As Code postal 3668 Zone téléphonique 089 Démographie Population 2 562 hab. (01/01/2020) D...

Commuter rail station in Chicago, Illinois 51st, 53rd St./Hyde ParkAt Lake Park AvenueHyde Park/51st–53rd Street stationGeneral informationLocation53rd Street at Lake Park AvenueHyde Park, Chicago, ILCoordinates41°48′04″N 87°35′14″W / 41.8010°N 87.5872°W / 41.8010; -87.5872Owned byMetraLine(s)University Park Sub DistrictPlatforms2 island platforms (formerly 3)[citation needed]Tracks4ConnectionsCTA BusConstructionAccessibleYesOther informationFare ...

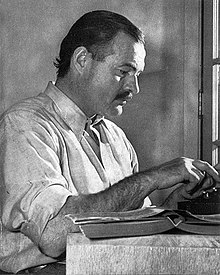

For other uses, see Ernest (disambiguation). ErnestErnest Hemingway, one of the most famous bearers.Pronunciation/ɜːrnɪst/GendermaleOriginWord/nameGermanicMeaningearnest, serious, warriorRegion of originNorthern Europe, Central EuropeOther namesRelated namesErnestine, Erna (female forms), Ernst, Ernesto, Ernestas, Ernő Ernest is a given name derived from Germanic word ernst, meaning serious. Notable people and fictional characters with the name include: People Archduke Ernest of Austria (...

LGBT rights in GuyanaGuyanaStatusIllegalPenaltyUp to life in prison (not enforced; decriminalisation proposed)Gender identityNoMilitaryNoDiscrimination protectionsNoneFamily rightsRecognition of relationshipsNo recognition of same-sex relationshipsAdoptionUnclear Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Guyana face legal and societal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Guyana is the only country in South America, and the only mainland country in the Americas, wh...

Sodium decavanadate Identifiers CAS Number (anhydrous): 12315-57-0 N 3D model (JSmol) (anhydrous): Interactive image ChemSpider (anhydrous): 34997594 EC Number (anhydrous): 235-375-1 PubChem CID (anhydrous): 118856830 InChI InChI=1S/6Na.28O.10V/q6*+1;28*-2;10*+5Key: WSNCYQDYQWKFLZ-UHFFFAOYSA-N SMILES (anhydrous): [O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-2].[O-...

State's participation as a Union slave state; a border state See also: American Civil War, Origins of the American Civil War, and Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area Union states in the American Civil War California Connecticut Delaware Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New York Ohio Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island Vermont West Virginia Wisconsin Dual governments Kentucky Missouri Virginia West Virginia Territories a...

American composer and typeface designer (born 1958) David Rakowski (born June 13, 1958, St. Albans, Vermont) is an American composer and typeface designer.[1][2] He studied under such composers as Robert Ceely, John Heiss, Milton Babbitt, Peter Westergaard, Paul Lansky, and Luciano Berio. In 2006, he was awarded the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center's 2004–2006 Elise L. Stoeger Prize.[3] He has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Music: in 1999 for...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (فبراير 2016) مركز المطيوي الجنوبي المطيوي الجنوبي المطيوي الجنوبي تقسيم إداري البلد السعودية مركز منطقة القصيم خ�...

Lauri Allan TörniLarry Thorne[nb 1]Thorne sebagai kapten tentara AmerikaJulukanLasseLahir(1919-05-28)28 Mei 1919Viipuri, FinlandMeninggal18 Oktober 1965(1965-10-18) (umur 46)Distrik Phước Sơn, Provinsi Quảng Nam, Vietnam[1]DikebumikanArlington National CemeteryPengabdian Finland Nazi Germany United States[2]Dinas/cabangFinnish ArmyWaffen SSUnited States ArmyLama dinas1938–19451954–1965PangkatKapten (Finlandia)Hauptsturmführer[2] ...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant les amblypyges. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations du projet arachnologie. Damon variegatus Damon variegatus du parc national Kruger en Afrique du SudClassification Règne Animalia Embranchement Arthropoda Sous-embr. Chelicerata Classe Arachnida Ordre Amblypygi Sous-ordre Euamblypygi Infra-ordre Neoamblypygi Super-famille Phrynoidea Famille Phrynichidae Sous-famille Damoninae Genre Damon...

American journalist Sarah Kaufman (born 1963)[1] is an American author who was the dance critic for the Washington Post. She was the recipient of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. Her most recent work, The Art of Grace, was published by W.W. Norton and Company in fall of 2015. Biography Kaufman was born in Austin, Texas, and was raised in Washington DC.[1] She earned a BA in English from the University of Maryland, where she studied under poet laureate Reed Whittemore. ...

Urban administrative region in Minas Gerais, Brazil See also: List of Intermediate and Immediate Geographic Regions of Minas Gerais The Immediate Geographic Region of Santa Bárbara-Ouro Preto is one of the 10 immediate geographic regions in the Intermediate Geographic Region of Belo Horizonte, one of the 70 immediate geographic regions in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais and one of the 509 of Brazil, created by the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2017.[1] ...

Letak Kokurakita-ku di Kitakyushu Kator distrik kota Kokurakita-ku Kokurakita-ku (小倉北区code: ja is deprecated ) (小倉北区?) adalah sebuah distrik kota dari Kitakyushu, Fukuoka, Jepang. Distrik ini adalah bagian utara dari mantan kota Kota Kokura sebelum bergabung bersama lima kota lainnya untuk menciptakan kota baru Kitakyushu pada tahun 1963. Stasiun Kokura JR Kyushu merupakan pusat utama kereta api Kitakyushu dan Sanyo Shinkansen pun berakhir di distrik kota ini. Penduduk: 184.54...

Vasco da Gama Tower is the tallest building in Portugal since 1998. This is a list of the tallest buildings in Portugal. Since 1998 the tallest building in Portugal has been the 145-metre (476 ft) Torre Vasco da Gama in Lisbon. The list only contains buildings at least 80 metres (260 ft) high. Tallest completed buildings This list ranks all finished buildings in Portugal that stand at least 80 metres (260 ft) tall. Rank Name City Image Height (m) Height (ft) Floors Year Notes ...