John Woodward (naturalist)

|

Read other articles:

GasolineSampul versi Digital dan VHSAlbum studio karya KeyDirilis30 Agustus 2022 (2022-08-30)GenreK-popDurasi36:56BahasaKoreaInggrisLabel SM Dreamus Kronologi Key Bad Love(2021) Gasoline(2022) Good & Great(2023) Singel dalam album Gasoline GasolineDirilis: 30 Agustus 2022 Sampul KillerSampul digital Singel dalam album Killer KillerDirilis: 13 Februari 2023 Gasoline adalah album studio kedua dari penyanyi Korea Selatan Key. Album ini dirilis pada tanggal 30 Agustus 2022, melalui S...

Untuk versi Britania, lihat Drunk History (seri TV Britania). Drunk HistoryGenreKomedi televisiPembuat Derek Waters SutradaraJeremy KonnerPresenterDerek WatersPemeran Bennie Arthur Tim Baltz Maria Blasucci Mort Burke Sarah Burns Craig Cackowski Michael Cassady Michael Coleman Aasha Davis Tymberlee Hill Adam Nee JT Palmer Greg Tuculescu MusikDan GrossNegara asalAmerika SerikatBahasa asliInggrisJmlh. musim6Jmlh. episode70 (dan 2 acara khusus) (daftar episode)ProduksiProduser eksekutif Derek Wat...

Gouvernement Camille Chautemps (1) Troisième République Données clés Président de la République Gaston Doumergue Président du Conseil Camille Chautemps Formation 21 février 1930 Fin 25 février 1930 Durée 4 jours Composition initiale Coalition PRRRS-RI-PRS-dissidents AD-PSF Représentation XIVe législature 242 / 602 Gouvernement André Tardieu I Gouvernement André Tardieu II modifier - modifier le code - voir Wikidata (aide) Le premier gouvernement Camille Chautem...

Bagian dari seri mengenaiKelengkapan Heraldik Unsur-Unsur Lambang Kebesaran Perisai Bidang Penopang Jambul Bulang Hulu Mantel Ketopong Mahkota Lapik Perempat Semboyan (atau slogan) Lambang Kebesaran Hulu lbs Latar dalam heraldik adalah keseluruhan permukaan perisai dalam gambar lambang kebesaran. Latar biasanya dilapisi dengan satu atau lebih pulasan (warna, logam, atau kulit bulu). Latar dapat dibagi-bagi menjadi beberapa bidang, dan dapat pula dihiasi dengan pola berwarna-warni. Dalam segel...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Bain. Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne s'appuie pas, ou pas assez, sur des sources secondaires ou tertiaires (juillet 2014). Pour améliorer la vérifiabilité de l'article ainsi que son intérêt encyclopédique, il est nécessaire, quand des sources primaires sont citées, de les associer à des analyses faites par des sources secondaires. Cet article est une ébauche concernant une entreprise....

Questa voce sull'argomento cardinali spagnoli è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Pedro Gómez Sarmiento de Villandrandocardinale di Santa Romana ChiesaIl vescovo Sarmiento (4º da sinistra) al battesimo di Filippo II di Spagna nel 1527, in un mosaico del 1939 presso il Palacio de Pimentel a Valladolid Incarichi ricoperti Vescovo di Tui (1523-1524) Vescovo di Badajoz (1524-1525) Vescovo di Palencia (1525-1534) Arcivescovo metropolita...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando la serie a fumetti di genere nero, vedi Spiderman - L'uomo ragno. Spider-Man - L'Uomo Ragnoserie TV d'animazione Il logo originale della serie Titolo orig.Spider-Man Lingua orig.inglese PaeseStati Uniti AutoreStan Lee, Steve Ditko (personaggi) RegiaBob Richardson, Robert Shellhorn (un episodio) ProduttoreJohn Semper SoggettoJohn Semper Char. designDel Barras MusicheShuki Levy, Haim Saban, Udi Harpaz StudioMarvel ...

Soccer knockout tournament in the US Not to be confused with U.S. Cup, U.S. Open, American Cup, America's Cup, or MLS Cup. Lamar Hunt Cup redirects here. Not to be confused with Lamar Hunt Trophy. Football tournamentLamar Hunt U.S. Open CupFounded1914RegionUnited States (CONCACAF)Number of teams100 (2023)Current championsHouston Dynamo FC (2nd title)Most successful club(s)Bethlehem Steel F.C. and Maccabee Los Angeles (5 titles each)Websiteussoccer.com/u...

Extensor muscle located medially in the thigh that extends the knee Vastus medialisMuscles of lower extremityDetailsOriginMedial side of femurInsertionQuadriceps tendonArteryFemoral arteryNerveFemoral nerveActionsExtends kneeIdentifiersLatinmusculus vastus medialis or musculus vastus internusTA98A04.7.02.023TA22620FMA22432Anatomical terms of muscle[edit on Wikidata] The vastus medialis (vastus internus or teardrop muscle) is an extensor muscle located medially in the thigh that extends th...

Album by Lionel Richie Just GoStudio album by Lionel RichieReleasedMarch 13, 2009GenreR&B[1]Length59:17LabelIslandProducer Akon JB & Corron John Ewbank Nando Eweg David Foster Clayton Haraba Martin K. Sean K. Stargate Tricky Stewart Lionel Richie chronology Sounds of the Season(2006) Just Go(2009) Tuskegee(2012) Singles from Just Go Face in the CrowdReleased: July 18, 2008 (NL) Good MorningReleased: December 15, 2008 Just GoReleased: March 12, 2009 (UK) I'm in LoveReleased...

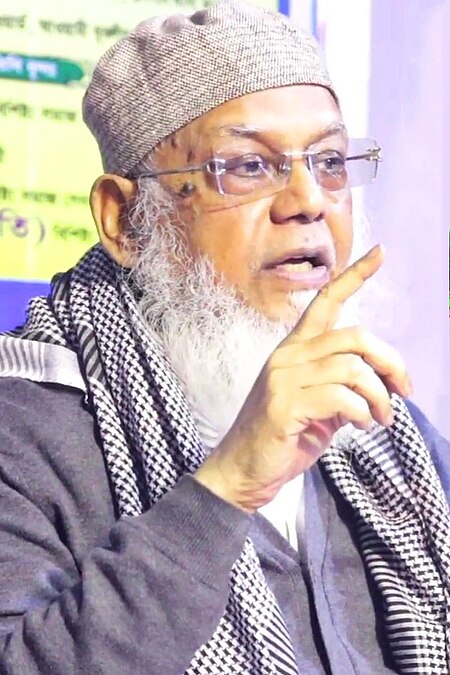

Bangladeshi Islamic Scholar (born 1950) AllamahFarid Uddin MasoodMasood in 2023Grand Imam, Sholakia National EidgahIncumbentAssumed office 2009Preceded byAbul Khair Muhammad SaifullahChairman, National Religious Madrasa Education Board of BangladeshIncumbentAssumed office 15 October 2016President, Bangladesh Jamiyatul UlamaIncumbentAssumed office 2014 Personal detailsBorn (1950-03-07) March 7, 1950 (age 74)Hijlia, Pakundia, KishoreganjNationalityBangladeshiChildren4Alma mater...

马来西亚—英国关系 马来西亚 英国 代表機構马来西亚驻英国高级专员公署(英语:High Commission of Malaysia, London)英国驻马来西亚高级专员公署(英语:British High Commission, Kuala Lumpur)代表高级专员 阿末拉席迪高级专员 查尔斯·海伊(英语:Charles Hay (diplomat)) 马来西亚—英国关系(英語:Malaysia–United Kingdom relations;馬來語:Hubungan Malaysia–United Kingdom)是指马来西亚与英国�...

74th season in franchise history; seventh Super Bowl appearance 2019 San Francisco 49ers seasonOwnerJed YorkGeneral managerJohn LynchHead coachKyle ShanahanHome fieldLevi's StadiumResultsRecord13–3Division place1st NFC WestPlayoff finishWon Divisional Playoffs(vs. Vikings) 27–10Won NFC Championship(vs. Packers) 37–20Lost Super Bowl LIV(vs. Chiefs) 20–31Pro Bowlers 4 Selected but did not participate due to participation in Super Bowl LIV:DE Nick BosaFB Kyle JuszczykTE George Kittl...

Student wing of the UK Labour Party Not to be confused with Labor Students. Labour Clubs redirects here. For the social clubs, see National Union of Labour and Socialist Clubs. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Labour Students – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2017) (Learn how ...

Calouste GulbenkianGCCLahirCalouste Sarkis Gulbenkian(1869-03-23)23 Maret 1869Scutari, Konstantinopel, Kesultanan Utsmaniyah (sekarang Üsküdar, Istanbul, Turki)Meninggal20 Juli 1955(1955-07-20) (umur 86)Lisbon, PortugalMakamGereja St. Sarkis Armenian, LondonWarga negaraBritish (from 1902)OttomanAlmamaterKing's College LondonPekerjaanPebisnis di Industri PerminyakanTahun aktif1895–1955OrganisasiTurkish Petroleum CompanyIraq Petroleum CompanySuami/istriNevarte EssayanAnakNubar Sa...

Alcon EntertainmentJenisSwastaIndustriFilmDidirikan1997[1]PendiriBroderick Johnson (presiden)Andrew Kosove (presiden)KantorpusatLos Angeles, CaliforniaTokohkunciSteven Wegner (WP pengembangan)Scott Parish (CFO)Kira Davis (mantan WP produksi & pemasaran)Situs webwww.alconent.com Alcon Entertainment LLC adalah perusahaan produksi film Amerika Serikat yang didirikan tahun 1997 oleh produser film Broderick Johnson dan Andrew Kosove. Sejak didirikan, Alcon Entertainment mengembangkan d...

Royal house of France from 987 to 1328 Capet redirects here. For the surname, see Capet (surname). For a full history of the Capetian family, see Capetian dynasty. House of CapetHouse of FranceArms of the Kingdom of FranceParent houseCapetian dynastyCountry Kingdom of France Kingdom of Navarre Kingdom of England (claimant) Founded987; 1037 years ago (987)FounderHugh CapetFinal rulerJoan II of NavarreTitles King of France King of Navarre Estate(s)France, NavarreDissolution132...

Languages and dialects developed in the Jewish diaspora Part of a series onJews and Judaism Etymology Who is a Jew? Religion God in Judaism (names) Principles of faith Mitzvot (613) Halakha Shabbat Holidays Prayer Tzedakah Land of Israel Brit Bar and bat mitzvah Marriage Bereavement Baal teshuva Philosophy Ethics Kabbalah Customs Rites Synagogue Rabbi Texts Tanakh Torah Nevi'im Ketuvim Talmud Mishnah Gemara Rabbinic Midrash Tosefta Targum Beit Yosef Mishneh Torah Tur Shulc...

يو بي-13 الجنسية ألمانيا النازية الشركة الصانعة إيه جي فيزر المالك البحرية الإمبراطورية الألمانية المشغل البحرية الإمبراطورية الألمانية المشغلون الحاليون وسيط property غير متوفر. المشغلون السابقون وسيط property غير متوفر. التكلفة وسيط property غير متوفر. منظومة التعاريف ا�...

This article is about the 2004 score. For the 2004 soundtrack for the same film, see The Punisher: The Album. 2004 film score by Carlo SiliottoThe PunisherFilm score by Carlo SiliottoReleasedJune 15, 2004GenreOrchestralFilm scoreLength67:41LabelLa-La LandProducerMichael GerhardCarlo SiliottoCarlo Siliotto chronology Julius Caesar (miniseries)(2003) The Punisher(2004) Nomad (2005 film)(2005) Punisher film music chronology The Punisher: The Album(2004) Original Score from the Motion Pic...