James Baskett

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada November 2022. Dalam nama yang mengikuti kebiasaan penamaan Slavia Timur ini, patronimiknya adalah Spasova. Ekaterina Zaharieva Menteri Urusan Luar NegeriMasa jabatan4 Mei 2017 – 12 Mei 2021Perdana MenteriBoyko Borisov PendahuluRadi NaydenovPenggantiSvetl...

In this Burmese name, Shin is an honorific, not a given name. Queen consort of Hanthawaddy Shin Mi-Nauk ရှင်မိနောက်As the Anauk Mibaya natQueen consort of HanthawaddyTenurec. July 1408 – c. December 1421?Queen of the Western Palace of AvaTenure25 November 1400 – c. July 1408PredecessorSaw Taw OoSuccessorShin Bo-MeBorn1374[note 1]MohnyinDied?Pegu (Pegu)SpouseMinkhaung I (1389–1408) Razadarit (1408–21)IssueMinye Kyawswa Saw Pyei Chantha Minye Thihathu Minye...

American politician (born 1952) This article is about the U.S. representative from Massachusetts. For other people with the same name, see William Keating. Bill KeatingMember of theU.S. House of Representativesfrom MassachusettsIncumbentAssumed office January 3, 2011Preceded byBill DelahuntConstituency10th district (2011–2013)9th district (2013–present)District Attorney of Norfolk CountyIn officeJanuary 3, 1999 – January 3, 2011Preceded byJeffrey LockeSucceeded byMichael Mo...

Radio station in Abilene, TexasKMWXAbilene, TexasBroadcast areaAbilene, TexasFrequency92.5 MHzBranding92.5 The RanchProgrammingFormatRed dirt countryAffiliationsHouston Texans Radio NetworkOwnershipOwnerTownsquare Media(Townsquare License, LLC)Sister stationsKEAN-FM, KEYJ-FM, KSLI, KULL, KYYWHistoryFirst air date1997 (as KROW)Former call signsKFXJ (1989-1997)KROW (1997-1998)KULL (1998-2012)Call sign meaningSimilar to mix (former branding)Technical informationFacility ID22158ClassC2ERP27,500 w...

Lampu minyak tanah liat India kontemporer sederhana saat deepawali Lampu minyak perunggu kuno dengan Chi Rho, sebuah simbol Kristen (replika) Lampu minyak Sukunda dari Lembah Kathmandu, Nepal Lampu minyak, teplok, cempor atau sentir adalah sebuah benda yang digunakan untuk menghasilkan cahaya selama beberapa waktu menggunakan sumber bahan bakar berbahan dasar minyak. Penggunaan lampu minyak dimulai ribuan tahun lalu dan berlanjut sampai sekarang, meskipun tidak secara meluas. Benda ini sering...

American political newspaper and website The HillTypeDaily newspaper (when Congress is in session)FormatCompactOwner(s)Nexstar Media GroupFounder(s)Jerry FinkelsteinMartin TolchinEditorBob CusackManaging editorIan Swanson[1]Photo editorGreg NashFoundedSeptember 1, 1994; 29 years ago (1994-09-01)LanguageAmerican EnglishHeadquarters1625 K St., NW, Suite 900, Washington, D.C., 20006 U.S.38°54′11″N 77°02′15″W / 38.90306°N 77.03750°W / ...

Barlow ParkLocationCrn Scott & Severin St, Parramatta Park, Cairns, QueenslandCoordinates16°55′49″S 145°46′2″E / 16.93028°S 145.76722°E / -16.93028; 145.76722Capacity16,700 (1,700 seated)TenantsNorthern Pride RLFC Barlow Park is a multi-sports facility and stadium in Parramatta Park, Cairns, Queensland, Australia. The Park is home of the Northern Pride RLFC offices, Cairns District Rugby Union, Cairns and District Athletics Association, Australian Spor...

1641 book by Descartes First Meditation redirects here. For the jazz album, see First Meditations. Meditations on First Philosophy The title page of the MeditationsAuthorRené DescartesOriginal titleMeditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstraturLanguageLatinSubjectPhilosophicalPublication date1641Original textMeditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstratur at Latin WikisourceTranslationMeditations ...

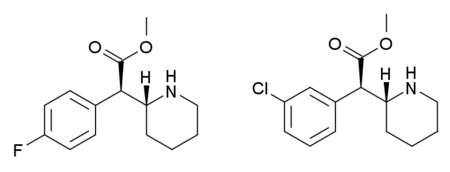

Stimulant drug 4-MethylmethylphenidateLegal statusLegal status CA: Schedule III DE: NpSG (Industrial and scientific use only) UK: Class B Identifiers IUPAC name methyl (2R)-2-(4-methylphenyl)-2-[(2R)-piperidin-2-yl]acetate CAS Number191790-79-1 Y 680996-70-7 (hydrochloride)PubChem CID44296147ChemSpider8281556 YUNII1Y11XUO4EYChemical and physical dataFormulaC15H21NO2Molar mass247.338 g·mol−13D model (JSmol)Interactive image SMILES Cc2ccc(cc2)C(C(=O)OC)C1CCCCN1 ...

Questa voce sull'argomento contee della Virginia è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Contea di SurryconteaLocalizzazioneStato Stati Uniti Stato federato Virginia AmministrazioneCapoluogoSurry Data di istituzione1652 TerritorioCoordinatedel capoluogo37°07′00.88″N 76°53′17.92″W / 37.11691°N 76.88831°W37.11691; -76.88831 (Contea di Surry)Coordinate: 37°07′00.88″N 76°53′17.92″W / ...

Министерство природных ресурсов и экологии Российской Федерациисокращённо: Минприроды России Общая информация Страна Россия Юрисдикция Россия Дата создания 12 мая 2008 Предшественники Министерство природных ресурсов Российской Федерации (1996—1998)Министерство охраны...

此條目可能包含不适用或被曲解的引用资料,部分内容的准确性无法被证實。 (2023年1月5日)请协助校核其中的错误以改善这篇条目。详情请参见条目的讨论页。 各国相关 主題列表 索引 国内生产总值 石油储量 国防预算 武装部队(军事) 官方语言 人口統計 人口密度 生育率 出生率 死亡率 自杀率 谋杀率 失业率 储蓄率 识字率 出口额 进口额 煤产量 发电量 监禁率 死刑 国债 ...

Shopping mall in Yerevan, ArmeniaDalma Garden MallLocationMalatia-Sebastia DistrictYerevan, ArmeniaCoordinates40°10′48″N 44°29′19″E / 40.179906°N 44.488531°E / 40.179906; 44.488531AddressTsitsernakaberd Highway 3, Yerevan 0082Opening dateOctober 2012DeveloperDalma InvestOwnerTashir GroupNo. of stores and services116Total retail floor area43,500 square metres (468,000 sq ft)No. of floors3Parking500+Websitedalma.am Dalma Garden Mall (Armenian: Դա�...

Dalam artikel ini, nama keluarganya adalah Aung Ye Lin. Aung Ye LinLin pada Myanmar International Fashion Week 2016Nama asalအောင်ရဲလင်းLahirAung Ye Lin19 Juni 1988 (umur 35)Yangon, MyanmarKebangsaanBurmaPekerjaanActor • ModelTahun aktif2005–sekarangKerabatPhyo Ye Lin (saudara laki-laki) Aung Ye Lin (bahasa Burma: အောင်ရဲလင်း; lahir 19 Juni 1988) adalah pemeran dan model Myanmar.[1][2][3] Filmografi Film...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento Giappone non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Futanari (ふたなり?) è un termine giapponese che letteralmente significa doppia forma; questo termine viene usato per riferirsi a materiale pornografico hentai i cui protagonisti sono ermafroditi oppure per ...

Service for hosting websites An example of rack mounted servers Part of a series onInternet hosting service Full-featured hosting Virtual private server Dedicated hosting Colocation centre Cloud computing Peer-to-peer Web hosting Shared Clustered Application-specific web hosting Blog (comments) Guild hosting service Image Video Wiki farms Application Social network By content format File Image Video Music Other types Remote backup Game server Home server DNS Email vte A web hosting service is...

Clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information Face of the Prague astronomical clock, in Old Town Square An astronomical clock, horologium, or orloj is a clock with special mechanisms and dials to display astronomical information, such as the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, zodiacal constellations, and sometimes major planets. Definition The astrarium made by the Italian astronomer and physician Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio showed the hour, the yearly calenda...

Jan LucemburskýJan I sebagai Raja BohemiaRaja BohemiaBerkuasa1310–1346Penobatan7 Februari 1311, Praha[1]PendahuluHeinrichPenerusKaisar Karl IVComte Luksemburg, Arlon dan DurbuyBerkuasa1313-1346PendahuluHeinrich VIIPenerusKaisar Karl IVKelahiran10 Agustus 1296LuksemburgKematian26 Agustus 1346 (usia 50 tahun)di dekat Crécy-en-PonthieuPemakamanKloster Altmünster (Biara Minster Kuno) di LuksemburgPasanganEliškaBeatriceKeturunanMarkétaJitkaKarl IV, Kaisar Romawi SuciJan JindřichAnn...

Series of interceptor aircraft Tornado ADV RAF Tornado F3 of No. 111 (Fighter) Squadron Role InterceptorType of aircraft Manufacturer Panavia Aircraft GmbH First flight 27 October 1979 Introduction 1 May 1985 Status Retired Primary users Royal Air Force (historical)Royal Saudi Air Force (historical) Italian Air Force (historical) Number built 194[1] Developed from Panavia Tornado IDS The Panavia Tornado Air Defence Variant (ADV) is a long-range, twin-engine swing-wing interceptor...

Non-fiction book by Caroline Fraser God's Perfect Child First editionAuthorCaroline FraserLanguageEnglishSubjectChristian Science and The First Church of Christ, ScientistGenreNon-fictionPublisherMetropolitan BooksPublication date1999Publication placeUnited StatesPages656 (2019 Picador edition)ISBN978-1250219046OCLC1050277946Websitewww.godsperfectchild.com/ God's Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church (1999) is a book by the American writer Caroline Fraser about Chris...