Helium atom scattering (HAS) is a surface analysis technique used in materials science. It provides information about the surface structure and lattice dynamics of a material by measuring the diffracted atoms from a monochromatic helium beam incident on the sample.

History

The first recorded helium diffraction experiment was completed in 1930 by Immanuel Estermann and Otto Stern[1] on the (100) crystal face of lithium fluoride. This experimentally established the feasibility of atom diffraction when the de Broglie wavelength, λ, of the impinging atoms is on the order of the interatomic spacing of the material. At the time, the major limit to the experimental resolution of this method was due to the large velocity spread of the helium beam. It wasn't until the development of high pressure nozzle sources capable of producing intense and strongly monochromatic beams in the 1970s that HAS gained popularity for probing surface structure. Interest in studying the collision of rarefied gases with solid surfaces was helped by a connection with aeronautics and space problems of the time. Plenty of studies showing the fine structures in the diffraction pattern of materials using helium atom scattering were published in the 1970s. However, it wasn't until a third generation of nozzle beam sources was developed, around 1980, that studies of surface phonons could be made by helium atom scattering. These nozzle beam sources were capable of producing helium atom beams with an energy resolution of less than 1meV, making it possible to explicitly resolve the very small energy changes resulting from the inelastic collision of a helium atom with the vibrational modes of a solid surface, so HAS could now be used to probe lattice dynamics. The first measurement of such a surface phonon dispersion curve was reported in 1981,[2] leading to a renewed interest in helium atom scattering applications, particularly for the study of surface dynamics.

Basic principles

Surface sensitivity

Generally speaking, surface bonding is different from the bonding within the bulk of a material. In order to accurately model and describe the surface characteristics and properties of a material, it is necessary to understand the specific bonding mechanisms at work at the surface. To do this, one must employ a technique that is able to probe only the surface, we call such a technique "surface-sensitive". That is, the 'observing' particle (whether it be an electron, a neutron, or an atom) needs to be able to only 'see' (gather information from) the surface. If the penetration depth of the incident particle is too deep into the sample, the information it carries out of the sample for detection will contain contributions not only from the surface, but also from the bulk material. While there are several techniques that probe only the first few monolayers of a material, such as low-energy electron diffraction (LEED), helium atom scattering is unique in that it does not penetrate the surface of the sample at all! In fact, the scattering 'turnaround' point of the helium atom is 3-4 angstroms above the surface plane of atoms on the material. Therefore, the information carried out in the scattered helium atom comes solely from the very surface of the sample.

A visual comparison of helium scattering and electron scattering is shown below:

![]()

Helium at thermal energies can be modeled classically as scattering from a hard potential wall, with the location of scattering points representing a constant electron density surface. Since single scattering dominates the helium-surface interactions, the collected helium signal easily gives information on the surface structure without the complications of considering multiple electron scattering events (such as in LEED).

Scattering mechanism

A qualitative sketch of the elastic one-dimensional interaction potential between the incident helium atom and an atom on the surface of the sample is shown here:

This potential can be broken down into an attractive portion due to Van der Waals forces, which dominates over large separation distances, and a steep repulsive force due to electrostatic repulsion of the positive nuclei, which dominates the short distances. To modify the potential for a two-dimensional surface, a function is added to describe the surface atomic corrugations of the sample. The resulting three-dimensional potential can be modeled as a corrugated Morse potential as:[3]

![{\displaystyle V(z)=D{\big \{}\exp \left[-2\alpha (z-z_{m})\right]-2\exp \left[-\alpha (z-z_{m}>)\right]{\big \}}+2\beta D\exp \left[2\alpha (z-z_{m})\right]\xi (x,y)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dd1de8c011faf4080cba013c9252a1a19401d93f)

The first term is for the laterally-averaged surface potential - a potential well with a depth D at the minimum of z = zm and a fitting parameter α, and the second term is the repulsive potential modified by the corrugation function, ξ(x,y), with the same periodicity as the surface and fitting parameter β.

Helium atoms, in general, can be scattered either elastically (with no energy transfer to or from the crystal surface) or inelastically through excitation or deexcitation of the surface vibrational modes (phonon creation or annihilation). Each of these scattering results can be used in order to study different properties of a material's surface.

Why use helium atoms?

There are several advantages to using helium atoms as compared with x-rays, neutrons, and electrons to probe a surface and study its structures and phonon dynamics. As mentioned previously, the lightweight helium atoms at thermal energies do not penetrate into the bulk of the material being studied. This means that in addition to being strictly surface-sensitive they are truly non-destructive to the sample. Their de Broglie wavelength is also on the order of the interatomic spacing of materials, making them ideal probing particles. Since they are neutral, helium atoms are insensitive to surface charges. As a noble gas, the helium atoms are chemically inert. When used at thermal energies, as is the usual scenario, the helium atomic beam is an inert probe (chemically, electrically, magnetically, and mechanically). It is therefore capable of studying the surface structure and dynamics of a wide variety of materials, including those with reactive or metastable surfaces. A helium atom beam can even probe surfaces in the presence of electromagnetic fields and during ultra-high vacuum surface processing without interfering with the ongoing process. Because of this, helium atoms can be useful to make measurements of sputtering or annealing, and adsorbate layer depositions. Finally, because the thermal helium atom has no rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom and no available electronic transitions, only the translational kinetic energy of the incident and scattered beam need be analyzed in order to extract information about the surface.

Instrumentation

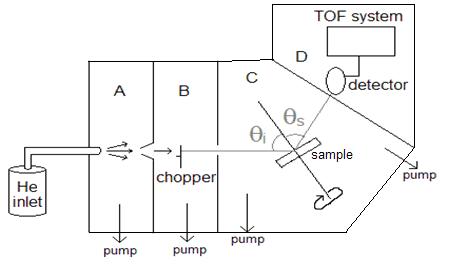

The accompanying figure is a general schematic of a helium atom scattering experimental setup. It consists of a nozzle beam source, an ultra high vacuum scattering chamber with a crystal manipulator, and a detector chamber. Every system can have a different particular arrangement and setup, but most will have this basic structure.

Sources

The helium atom beam, with a very narrow energy spread of less than 1meV, is created through free adiabatic expansion of helium at a pressure of ~200bar into a low-vacuum chamber through a small ~5-10μm nozzle.[4] Depending on the system operating temperature range, typical helium atom energies produced can be 5-200meV. A conical aperture between A and B called the skimmer extracts the center portion of the helium beam. At this point, the atoms of the helium beam should be moving with nearly uniform velocity. Also contained in section B is a chopper system, which is responsible for creating the beam pulses needed to generate the time of flight measurements to be discussed later.

Scattering chamber

The scattering chamber, area C, generally contains the crystal manipulator and any other analytical instruments that can be used to characterize the crystal surface. Equipment that can be included in the main scattering chamber includes a LEED screen (to make complementary measurements of the surface structure), an Auger analysis system (to determine the contamination level of the surface), a mass spectrometer (to monitor the vacuum quality and residual gas composition), and, for working with metal surfaces, an ion gun (for sputter cleaning of the sample surface). In order to maintain clean surfaces, the pressure in the scattering chamber needs to be in the range of 10−8 to 10−9 Pa. This requires the use of turbomolecular or cryogenic vacuum pumps.

Crystal manipulator

The crystal manipulator allows for at least three different motions of the sample. The azimuthal rotation allows the crystal to change the direction of the surface atoms, the tilt angle is used to set the normal of the crystal to be in the scattering plane, and the rotation of the manipulator around the z-axis alters the beam incidence angle. The crystal manipulator should also incorporate a system to control the temperature of the crystal.

Detector

After the beam scatters off the crystal surface, it goes into the detector area D. The most commonly used detector setup is an electron bombardment ion source followed by a mass filter and an electron multiplier. The beam is directed through a series of differential pumping stages that reduce the noise-to-signal ratio before hitting the detector. A time-of-flight analyzer can follow the detector to take energy loss measurements.

Elastic measurements

Under conditions for which elastic diffractive scattering dominates, the relative angular positions of the diffraction peaks reflect the geometric properties of the surface being examined. That is, the locations of the diffraction peaks reveal the symmetry of the two-dimensional space group that characterizes the observed surface of the crystal. The width of the diffraction peaks reflects the energy spread of the beam. The elastic scattering is governed by two kinematic conditions - conservation of energy and the energy of the momentum component parallel to the crystal:

Here G is a reciprocal lattice vector, kG and ki are the final and initial (incident) wave vectors of the helium atom. The Ewald sphere construction will determine the diffracted beams to be seen and the scattering angles at which they will appear. A characteristic diffraction pattern will appear, determined by the periodicity of the surface, in a similar manner to that seen for Bragg scattering in electron and x-ray diffraction. Most helium atom scattering studies will scan the detector in a plane defined by the incoming atomic beam direction and the surface normal, reducing the Ewald sphere to a circle of radius R=k0 intersecting only reciprocal lattice rods that lie in the scattering plane as shown here:

The intensities of the diffraction peaks provide information about the static gas-surface interaction potentials. Measuring the diffraction peak intensities under different incident beam conditions can reveal the surface corrugation (the surface electron density) of the outermost atoms on the surface.

Note that the detection of the helium atoms is much less efficient than for electrons, so the scattered intensity can only be determined for one point in k-space at a time. For an ideal surface, there should be no elastic scattering intensity between the observed diffraction peaks. If there is intensity seen here, it is due to a surface imperfection, such as steps or adatoms. From the angular position, width and intensity of the peaks, information is gained regarding the surface structure and symmetry, and the ordering of surface features.

Inelastic measurements

The inelastic scattering of the helium atom beam reveals the surface phonon dispersion for a material. At scattering angles far away from the specular or diffraction angles, the scattering intensity of the ordered surface is dominated by inelastic collisions.

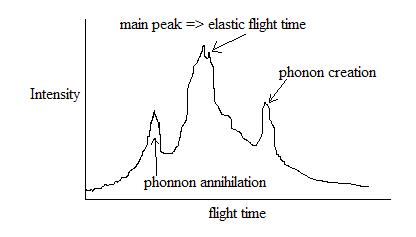

In order to study the inelastic scattering of the helium atom beam due only to single-phonon contributions, an energy analysis needs to be made of the scattered atoms. The most popular way to do this is through the use of time-of-flight (TOF) analysis. The TOF analysis requires the beam to be pulsed through the mechanical chopper, producing collimated beam 'packets' that have a 'time-of-flight' (TOF) to travel from the chopper to the detector. The beams that scatter inelastically will lose some energy in their encounter with the surface and therefore have a different velocity after scattering than they were incident with. The creation or annihilation of surface phonons can be measured, therefore, by the shifts in the energy of the scattered beam. By changing the scattering angles or incident beam energy, it is possible to sample inelastic scattering at different values of energy and momentum transfer, mapping out the dispersion relations for the surface modes. Analyzing the dispersion curves reveals sought-after information about the surface structure and bonding. A TOF analysis plot would show intensity peaks as a function of time. The main peak (with the highest intensity) is that for the unscattered helium beam 'packet'. A peak to the left is that for the annihilation of a phonon. If a phonon creation process occurred, it would appear as a peak to the right:

The qualitative sketch above shows what a time-of-flight plot might look like near a diffraction angle. However, as the crystal rotates away from the diffraction angle, the elastic (main) peak drops in intensity. The intensity never shrinks to zero even far from diffraction conditions, however, due to incoherent elastic scattering from surface defects. The intensity of the incoherent elastic peak and its dependence on scattering angle can therefore provide useful information about surface imperfections present on the crystal.

The kinematics of the phonon annihilation or creation process are extremely simple - conservation of energy and momentum can be combined to yield an equation for the energy exchange ΔE and momentum exchange q during the collision process. This inelastic scattering process is described as a phonon of energy ΔE = ℏω and wavevector q. The vibrational modes of the lattice can then be described by the dispersion relations ω(q), which give the possible phonon frequencies ω as a function of the phonon wavevector q.

In addition to detecting surface phonons, because of the low energy of the helium beam, low-frequency vibrations of adsorbates can be detected as well, leading to the determination of their potential energy.

References

Other

- E. Hulpke (Ed.), Helium Atom Scattering from Surfaces, Springer Series in Surface Sciences 27 (1992)

- G. Scoles (Ed.), Atomic and Molecular Beam Methods, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, New York (1992)

- J. B. Hudson, Surface Science - An Introduction, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1998)