De Quervain's thyroiditis

| |||||||||||

Read other articles:

Xavier Bettel Perdana Menteri Luksemburg ke-22Masa jabatan4 Desember 2013 – 17 November 2023Penguasa monarkiHenriWakilEtienne SchneiderDan KerschPaulette Lenert PendahuluJean-Claude JunckerPenggantiLuc FriedenWakil Perdana Menteri LuksemburgPetahanaMulai menjabat 17 November 2023Perdana MenteriLuc Frieden PendahuluPaulette LenertPenggantiPetahanaMenteri Luar Negeri dan EropaPetahanaMulai menjabat 17 November 2023 PendahuluJean AsselbornPenggantiPetahanaMenteri Komunikas...

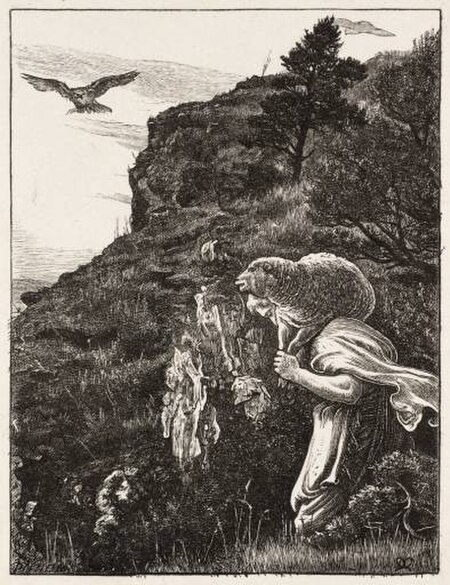

Domba yang hilang, karya Dalziel Bersaudara Perumpamaan tentang domba yang hilang adalah perumpamaan yang diajarkan oleh Yesus kepada murid-muridnya. Kisah ini tercantum di dalam Matius 18:12-14 dan Lukas 15:1-7. Matius 18:12-14: (Terjemahan Baru)Bagaimana pendapatmu? Jika seorang mempunyai seratus ekor domba, dan seekor di antaranya sesat, tidakkah ia akan meninggalkan yang sembilan puluh sembilan ekor di pegunungan dan pergi mencari yang sesat itu? Dan Aku berkata kepadamu: S...

Process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper This article is about techniques of printmaking as a fine art. For the history of printmaking in Europe, see Old master print. For the Japanese printmaking tradition, see Ukiyo-e. Katsushika Hokusai The Underwave off Kanagawa, 1829/1833, color woodcut, Rijksmuseum Collection Rembrandt, Self-portrait, etching, c. 1630 Francisco Goya, There is No One To Help Them, Disasters of War series, aquatint c. 1810 Printmaking is the...

Chemical compound ElinogrelClinical dataOther namesPRT-060128Routes ofadministrationBy mouth, IVATC codeNoneLegal statusLegal status Development terminated Pharmacokinetic dataMetabolismMainly unchanged, ~15% N-demethylation[1]ExcretionUrine, faecesIdentifiers IUPAC name N-[(5-Chlorothiophen-2-yl)sulfonyl]-N′-{4-[6-fluoro-7-(methylamino)-2,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydroquinazolin-3(2H)-yl]phenyl}urea CAS Number936500-94-6PubChem CID16066663ChemSpider17226246UNII915Y8E749JKEGGD09607CompTox Dash...

Peta infrastruktur dan tata guna lahan di Komune Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. = Kawasan perkotaan = Lahan subur = Padang rumput = Lahan pertanaman campuran = Hutan = Vegetasi perdu = Lahan basah = Anak sungaiLe Chambon-sur-Lignon adalah sebuah kota di Haute-Loire département di Auvergne région di Prancis selatan. Jumlah penduduknya (1999): 2,834. Penduduk kota ini umumnya adalah orang Protestan Huguenot. Kota ini menjadi tempat perlindungan orang-or...

HTC One X (international)HTC One XMerekOnePembuatHTC CorporationSeriHTC OneOperatorVodafone (UK), Orange (UK), T-Mobile (UK), O2 (UK), Three, Optus, Vodafone, Telstra, SingTel, M1, StarHub, Celcom, Digi, Telecom (NZ), 2degrees, Mobily (Saudi Arabia)Ketersediaan menurut negaraAustralia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Sweden, Thailand, the Philippines 02 April 2012 (2012-04-02)[1][2][3][4] United Kingdom 05 April 2012 (2012-04-05)[5] New...

Lampu Aldis Lampu sinyal adalah sebuah alat komunikasi yang mengisyaratkan sejumlah kode-kode tertentu dengan menggunakan cahaya. Umumnya kode yang digunakan adalah kode Morse. Penemu lampu isyarat adalah Arthur C. W. Aldis, karena itu alat ini juga sering disebut lampu Aldis. Secara sederhana, lampu isyarat digunakan dengan membuka dan menutup sebuah jendela atau penutup yang dipasang di depan lampu, dengan durasi yang beragam. Proses menutup dan membuka jendela ini bisa dioperasikan secara ...

Flag ratio: 2:3 Former flag used between 1970 and 1997 The current design of the flag of Johannesburg was adopted on 16 May 1997, replacing a previous version of the flag that had been in service since 20 October 1970. The design is a white-fimbriated vertical tricolour of blue, green, and red. The coat of arms of the city of Johannesburg is displayed in the centre of the flag on a green panel in the centre of a heraldic fret on a white disk on a black background. The flag clearly alludes to...

La musique australienne est composée de deux grands courants : celle indigène, issue des peuples aborigènes, et celle exogène, issue des colons britanniques. Les peuples aborigènes d'Australie ont conservé nombre de chants ancestraux et développé des instruments très particuliers, comme le didgeridoo[1]. Les colons britanniques des années 1700-1800 ont introduit une tradition de ballades de la musique folk qui ont été adaptées aux spécificités australiennes, comme Waltzin...

American computational biologist and journal editor Michael EisenBornMichael Bruce Eisen (1967-04-13) April 13, 1967 (age 57)Boston, Massachusetts, United StatesNationalityAmericanAlma materHarvard University (AB, PhD)Known forPublic Library of Science (PLOS)AwardsBenjamin Franklin Award (Bioinformatics) (2002)Scientific careerFields Biology Genetics Genomics Evolution Development[1] InstitutionsUniversity of California, BerkeleyThesisStructural Studies of Influenza A V...

Largest Norman castle in Ireland (ruin), Trim, County Meath This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This article needs additional citations for...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с такой фамилией, см. Росситер. Персиваль «Стюарт» Брайс Росситерангл. Percival «Stuart» Bryce Rossiter Дата рождения 1923[1][2] Место рождения Англия, Великобритания Дата смерти 1982[1][2] Место смерти Англия Гражданство (подданство) &...

British actor This article is about the English actor. For the American athlete, see Tom Courtney. SirTom CourtenayCourtenay in 2015BornThomas Daniel Courtenay (1937-02-25) 25 February 1937 (age 87)Hull, East Yorkshire, EnglandOccupationActorYears active1960–presentSpouses Cheryl Kennedy (m. 1973; div. 1982) Isabel Crossley (m. 1988) Sir Thomas Daniel Courtenay (/ˈkɔːrtni/; born 25 February 1937)...

Human settlement in Chicago, Illinois For the commuter rail line in Toronto, see Lakeshore East line. Lakeshore East map depictionLakeshore East from NEMA in 2021Lakeshore East from Cascade (east) with prominent views of Blue Cross Blue Shield Tower, Aon Center and Aqua May 2022Lakeshore East from St. Regis Chicago (north) with prominent views of buildings and Lakeshore Drive in December 2022 File: Lakeshore East is a master-planned mixed use urban development being built by the Magellan Deve...

الفارع تقسيم إداري البلد السعودية معلومات أخرى منطقة زمنية ت ع م+03:00 تعديل مصدري - تعديل الفارع قرية سعودية، تابعة لمركز الغريف في محافظة الكامل في منطقة مكة المكرمة.[1] الوصف تبعد القرية عن المركز مسافة 6 كيلو متر بإتجاه الشمال، نوع الطريق اسفلت. أقرب مدينة...

「アプリケーション」はこの項目へ転送されています。英語の意味については「wikt:応用」、「wikt:application」をご覧ください。 この記事には複数の問題があります。改善やノートページでの議論にご協力ください。 出典がまったく示されていないか不十分です。内容に関する文献や情報源が必要です。(2018年4月) 古い情報を更新する必要があります。(2021年3月)出...

Extinct in the wild (EW): 2 species Critically endangered (CR): 203 species Endangered (EN): 505 species Vulnerable (VU): 536 species Near threatened (NT): 345 species Least concern (LC): 3,306 species Data deficient (DD): 872 species Mammalian species (IUCN, 2020-1) 5850 extant species have been evaluated 4978 of those are fully assessed[a] 3651 are not threatened at present[b] 1244 to 2116 are threatened[c] 81 to 83 a...

Estadio Bicentenario Municipal Nelson Oyarzún Estadio de categoría A de la ANFPLocalizaciónPaís ChileLocalidad Chillán ÑubleChile ChileCoordenadas 36°37′05″S 72°06′27″O / -36.618056, -72.1075Detalles generalesNombres anteriores Estadio Municipal de Chillán (1961—1978)Estadio Municipal Nelson Oyarzún (1978—2008)Superficie CéspedDimensiones 106 x 72,5 mCapacidad 12 000 espectadoresPropietario Ilustre Municipalidad de ChillánConstrucciónCo...

United States government agencyThis article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety AdministrationSeal of the United States Department of TransportationLogo of the ...

English filmmaker (born 1971) Matthew Vaughan redirects here. For the politician, see Matthew Vaughan-Davies, 1st Baron Ystwyth. Matthew VaughnVaughn in 2019BornMatthew Allard Robert Vaughn (1971-03-07) 7 March 1971 (age 53)Paddington, London, EnglandOccupationsFilm directorfilm producerscreenwriterYears active1996–presentSpouse Claudia Schiffer (m. 2002)Children3 Matthew Allard de Vere Drummond (born Matthew Allard Robert Vaughn; 7 March 1971), know...