Castor and Pollux (Prado)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Duta Besar Amerika Serikat untuk BotswanaSegel Kementerian Dalam Negeri Amerika SerikatDicalonkan olehPresiden Amerika SerikatDitunjuk olehPresidendengan nasehat Senat Berikut ini adalah daftar Duta Besar Amerika Serikat untuk Botswana Daftar Charles J. Nelson David B. Bolen Donald R. Norland Horace Dawson Theodore C. Maino Natale H. Bellocchi John Florian Kordek David Passage Howard Franklin Jeter Robert Krueger John E. Lange Joseph Huggins Emil M. Skodon Katherine H. P. Canavan[1] S...

Frances Bean CobainLahir18 Agustus 1992 (umur 31)Los Angeles, California, Amerika SerikatOrang tuaKurt CobainCourtney Love Frances Bean Cobain (lahir 18 Agustus 1992) adalah anak semata wayang dari pasangan musisi almarhum Kurt Cobain (Nirvana) dan Courtney Love (Hole). Namanya diberikan oleh almarhum ayahnya, dari kombinasi nama Frances (dari nama depan Frances McKee, gitaris band The Vaselines),[1][2][3] dan Bean (yang berarti biji dalam Bahasa Inggris), karena...

Lambang Opoczno dengarkanⓘ - sebuah kota di Polandia tengah dengan 23.000 penduduk (2002). Terletak di provinsi Łódź (sejak 1999), sebelumnya di Provinsi Piotrkow Trybunalski (1975-1998). Tokoh terkenal dari Opoczno Edmund Biernacki Artikel bertopik geografi atau tempat Polandia ini adalah sebuah rintisan. Anda dapat membantu Wikipedia dengan mengembangkannya.lbs

Lukisan cat minyak View of Delft , oleh Johannes Vermeer. Cat minyak adalah cat yang terdiri atas partikel-partikel pigmen warna yang diikat (direkat) dengan media minyak pengikat pigmen warna yaitu minyak linen dapat juga dengan minyak papaver dalam bentuk pasta, sedangkan untuk mengencerkan cat tediri dari campuran terpentin dengan minyak linen.[1][2] Sejarah Cat minyak telah digunakan di Inggris sejak abad ke-13 untuk dekorasi sederhana. Sampai abad ke-15 belum banyak digun...

Provincia di Como Negara Italia Wilayah / Region Lombardia Ibu kota Como Area 1,288 km2 Population (2008) 582,736 Kepadatan 452 inhab./km2 Comuni 162 Nomor kendaraan CO Kode pos 22100 Kode area telepon 031 0344 02 0331 ISTAT 013 Presiden Leonardo Carioni Executive Lega Nord Peta yang menunjukan lokasi provinsi Como di Italia Como (Italia: Provincia di Comocode: it is deprecated ) adalah sebuah provinsi di regione Lombardia di Italia. Ibu kotanya berada di kota Como. Luasnya adalah 1.28...

Voivodeship of Poland Voivodeship in PolandSubcarpathian Voivodeship Województwo podkarpackieVoivodeship FlagCoat of armsBrandmarkLocation within PolandAdministrative mapCoordinates (Rzeszów): 50°2′1″N 22°0′17″E / 50.03361°N 22.00472°E / 50.03361; 22.00472Country PolandCapitalRzeszówCounties 4 cities, 21 land counties * KrosnoPrzemyślRzeszówTarnobrzegBieszczady CountyBrzozów CountyDębica CountyJarosław CountyJasło CountyKolbuszowa CountyKr...

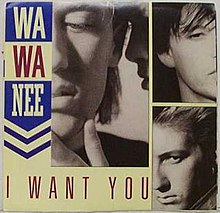

1989 single by Wa Wa NeeI Want YouSingle by Wa Wa Neefrom the album Blush Released8 May 1989[1]RecordedStudios 301, SydneyGenrePopLength3:26LabelCBS RecordsSongwriter(s)Paul GrayProducer(s)Robyn Smith, Paul GrayWa Wa Nee singles chronology So Good (1989) I Want You (1989) I Want You is a song from Australian pop group Wa Wa Nee. The song was released in May 1989 as the third and final single from their second studio album, Blush (1989). It was the band's final release before disbandi...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Oktober 2016. Berikut adalah daftar spesies Salticidae K-M pada 16 Desember 2009. Kalcerrytus Kalcerrytus Galiano, 2000 Kalcerrytus amapari Galiano, 2000—Brasil Kalcerrytus carvalhoi (Bauab & Soares, 1978)—Brasil Kalcerrytus chimore Galiano, 2000—Bolivia K...

RedoxRedox, dengan sistem penjendelaan Orbital berjalan, Maret 2017Perusahaan / pengembangJeremy Soller,Pengembang-pengembang Redox[1]Diprogram dalamRust, AssemblyKeluargaMirip UnixStatus terkiniAktifModel sumberSumber terbukaRilis perdana20 April 2015; 8 tahun lalu (2015-04-20)Rilis tak-stabil terkini0.1.1 / 28 Februari 2017; 7 tahun lalu (2017-02-28)Repositorigitlab.redox-os.org/redox-os/redox Target pemasaranKomputer meja, Stasiun kerja, Komputer peladen, Sistem bena...

Agung Sabar SantosoAgung Sabar Santoso sewaktu menjadi Kepala Kepolisian Daerah Sulawesi Tenggara (2015) Kepala Kepolisian Daerah BantenMasa jabatan20 Desember 2019 – 1 Mei 2020PendahuluTomsi TohirPenggantiFiandarAsisten Perencanaan dan Anggaran KapolriMasa jabatan22 Januari 2019 – 20 Desember 2019PendahuluGatot Eddy PramonoPenggantiHendro SugiatnoWakil Inspektur Pengawasan Umum PolriMasa jabatan8 April 2018 – 22 Januari 2019PendahuluI Ketut Untung Yoga AnnaPe...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (سبتمبر 2019) آنا ناغي معلومات شخصية الميلاد 6 يونيو 1940 (84 سنة)[1] بودابست مواطنة المجر الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم جامعة الفنون المسرحية والسينمائية (1959�...

v · m 1917-1941 → Véhicules blindés soviétiques de la Seconde Guerre mondiale → 1945 à 1991 Véhicules blindés de combat Chenillettes T-27 Chenillettes T-27 K-6 Chenillette lance-flammes OT-27/KhT-27 (ru) KhT-37 (ru) Chenillette chimique BKhM-4 Chenillette poseuse de mines MZ-27 Chenillette-tracteur Tracteur T-27 Chenillette télécommandée TT-27 Chenillette-tracteur d'aérodrome AS-T-27 T-20 T-20 Automitrailleuses D-8 D-12 D-13 FAI BA-3/BA-6 BA-10 BA-11 BA-20 BA-21...

American politician Curt Meier30th Treasurer of WyomingIncumbentAssumed office January 7, 2019GovernorMark GordonPreceded byMark GordonMember of the Wyoming Senatefrom the 3rd districtIn officeJanuary 1995 – January 8, 2019Preceded byJim GeringerSucceeded byCheri Steinmetz Personal detailsBorn (1953-01-01) January 1, 1953 (age 71)La Grange, Wyoming, U.S.Political partyRepublicanSpouseCharleneEducationUniversity of Wyoming (BS) Curt Meier (born January 1, 1953) is an Americ...

Sign language from Ghardaïa, Algeria You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Hebrew. Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia. Do not translate text that appears...

LovćenŠtirovnik, puncak tertinggi LovćenTitik tertinggiKetinggian1.749 m (5.738 ft)Koordinat42°23′57″N 18°49′06″E / 42.3991°N 18.8184°E / 42.3991; 18.8184 GeografiLovćenLocation in MontenegroLetakMontenegro Mausoleum Njegoš di puncak Jezerski vrh Taman Nasional Lovćen Pasukan Montenegro di sekitar Lovćen, Oktober 1914. Lovćen (bahasa Serbo-Kroasia: Lovćen, Ловћен, pelafalan [ɫôːʋtɕen]) adalah gunung dan taman ...

Tavola periodica degli elementi Un elemento chimico è un atomo caratterizzato da un determinato numero di protoni. Gli elementi chimici sono i costituenti fondamentali delle sostanze e, fino al 2022, ne sono stati scoperti 118, dei quali 20 instabili in quanto radioattivi. Vengono ordinati in base al numero di protoni (numero atomico) nella tavola periodica degli elementi.[1][2][3] Gli atomi dello stesso elemento possono differire per il numero di neutroni e quindi pe...

Military group from 1515 to 1523 Frisian peasant rebellionPainting of Pier Gerlofs Donia, 1622Date1515–1523(8 years)LocationFriesland in what is now the NetherlandsResult Suppression of the rebellionBelligerents Habsburg Netherlands Arumer Zwarte Hoop Charles II, Duke of GueldersCommanders and leaders Charles VMargaret of Austria Pier Gerlofs Donia Wijerd Jelckama Maarten van RossumStrength unknown 4,000 (maximum) The Arumer Zwarte Hoop, meaning Black Army of Arum (West Frisian: Swarte...

Type of climbing Descent of the Southeast Face of the Höfats East Summit in a drawing by Ernst Platz in the 1896 German Alpine Club Yearbook Grass climbing (German: Grasklettern) is a type of climbing in which, unlike rock climbing, the climber has to scale very steep grass mountainsides, through which the underlying rock protrudes in places. Description This type of climbing is used in the Alps, especially in the Bavarian range known as the Allgäu Alps where the numerous grass mountains, w...

Hurricanes de la Caroline Données-clés Fondation 1972 Siège Raleigh (Caroline du Nord, États-Unis) Patinoire (aréna) PNC Arena(18 680 places) Couleurs Rouge, noir, blanc, argent Ligue Ligue nationale de hockey Association Association de l'Est Division Division Métropolitaine Capitaine Jordan Staal Capitaines adjoints Jordan MartinookJaccob SlavinSebastian...

E. T. Burrowes Company Rechtsform Company Gründung 1875 Auflösung ? Sitz Portland, Maine, USA Branche Glas Burrowes Model E von 1908 E. T. Burrowes Company war ein US-amerikanisches Unternehmen.[1][2] Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Unternehmensgeschichte 2 Fahrzeuge 3 Literatur 4 Weblinks 5 Einzelnachweise Unternehmensgeschichte Das Unternehmen wurde 1875 gegründet.[3] Es hatte seinen Sitz in Portland in Maine. Ursprünglich stellte es Glas her. Zwischen 1904 und 1908 entsta...