|

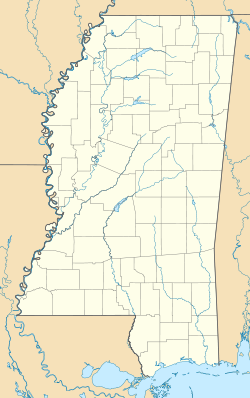

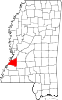

Bruinsburg, Mississippi

Bruinsburg is an extinct settlement in Claiborne County, Mississippi, United States.[1] Founded when the Natchez District was part of West Florida, the settlement was one of the end points of the Natchez Trace land route from Nashville to the lower Mississippi River valley. It was located on the south bank of Bayou Pierre, 3.0 mi (4.8 km) east of the Mississippi River, and thus was known in colonial and territorial days as the Bayou Pierre settlement. The town's port, Bruinsburg Landing, was located directly on the Mississippi River, just south of the mouth of the Bayou Pierre. Once an important commercial and military location, Bruinsburg, also spelled Bruinsburgh and Bruensburg, played roles in the territorial-era interregional slave trade, the Burr conspiracy of 1806, and the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. Nothing remains today of the village or its port.[2] History    The Mound Builders left one of their works at what came to be known in the early 19th century as Bruinsburg. Bruin was said to have built his house atop the mound,[3][4] and his wife was "intered at Bruin Mount" in 1807.[5] Immediately prior to colonization, the Bruinsburg area had been the domain of the Natchez people, but following the 1726 Natchez revolt against the French, the region was ethnically cleansed, and subsequently passed through the hands of the Choctaw, the British, and the Spanish, before being turned over to the Americans as part of the Natchez District of the Mississippi Territory in 1798.[6] Bayou Pierre before BruinBefore there was Bruinsburg, there was what was known as the Bayou Pierre settlement. According to Mann Butler, drawing from the account of British West Florida colonist Calvin Smith, there were a total of six white families in the Petit Gulf and Bayou Pierre settlements in 1776.[7] While advertising his plantation and sawmill for lease in 1802, Bruin stated that there had been a grist mill, apparently seated on the James' Run right-hand tributary, built "about thirty years ago, which stood many years...but was burned down by the Indians, and not since rebuilt."[8] Bruin added that James' Run was "settled by some families toward its source, in large cane breaks."[8] American Revolution to 1850sBruinsburg is named for Peter Bryan Bruin. The Bruins built their main residence and also their barn atop Indian mounds near the confluence of Bayou Pierre and the Mississippi River.[3][4] Bruin's settlement was "most northern settlement of the district at that time."[4] Bruin's daughter claimed that she and her father had arrived in Mississippi in 1784.[9] In 1794 Bruin signed contracts arranging for a sawmill to be constructed at Bayou Pierre by four hired slaves: "Stephen, Ben, Ben (mulatto), and Peter."[10] There had previously been a gristmill at the location.[10] On May 7, 1796, at one in the afternoon, a British traveler named Francis Bailey stopped at the settlement, writing in his journal that Bayou Pierre was "a little stream which rises up in the district of the Natchez, and upon the head waters of which, there are some settlements, which form part of that district; there were also two or three plantations at its mouth. Here we went ashore in our canoe, and got some eggs and milk, which were acceptable to us who had been so long deprived of every luxury of this kind. The land here was very nearly overflowed, being very few inches above the level of the river. The inhabitants told me they never remembered the river so high."[11] Bruinsburg was one of the endpoints of the ancient trail that was surveyed by the U.S. government as the "highway from Nashville in the State of Tennessee to the Grindstone ford of the Bayou Pierre in the Mississippi Territory," now known as the Natchez Trace. [12]: 198–199 The community also had a Mississippi River boat landing, and future U.S. President Andrew Jackson set up a trading post there during the 1790s.[2] Bruinsburg was one of the places where Jackson worked as a slave trader in the Natchez District, selling to local planters.[13][14][15][16] A old resident of Rodney, Mississippi, wrote that in those early days, Jackson "often in company with Bruin, Price, Crane, Freeland, Harmon and others, would engage in running races, wrestling and all those manly exercises common to new countries."[17] According to a history published in the Port Gibson Reveille newspaper, "A tiny village grew up [at Bruinsburg] containing several stores, a tavern, &c., and the place became a lively trading point for the interior country."[18] After the southern lands near the Mississippi River became American possessions, Bruinsburg was reportedly the first place in the newly organized Territory to hoist the American flag.[19] Bruin was appointed a territorial judge by President John Adams.[20] In 1802 he advertised that he was laying out an 11-street town at Bruinsburg, "SUBSCRIPTIONS will be received at Natchez, by Meffs. Robert and George Cochran, Ebenezer Rees, Bryan Bruin and at the Office of the Herald; at Cole's Creek by Thomas Calvit and John Giraults; at Bayou Pierre, by James Harmon, George W. Humphreys, Arthur Carney and William Scott; at Big Black, Tobias Brashears; at Fort Adams, by Capt. James Sterret."[21] In January 1807, former Vice-President Aaron Burr, who at the time was wanted on a charge of treason, visited Bruin while fleeing federal agents. As retold by J. F. H. Claiborne, "Early in January, of the coldest winter ever known here, Colonel Burr, with nine boats, arrived at the mouth of Bayou Pierre, and tied up on the western or Louisiana shore. He crossed over to the residence of Judge Bruin, (whom he had known in the revolutionary war) and there learned, for the first time, that the Territorial authorities would oppose his descent, though his landing on the Louisiana side would seem to indicate that he apprehended some opposition. He immediately wrote to Governor Mead, disavowing hostile intentions towards the Territory or the country; that he was en route to the Ouachitta to colonize his lands, and that any attempt to obstruct him would be illegal and might provoke civil war."[22] A witness at Burr's trial stated that Judge Bruin's place was a mile and a quarter below Bayou Pierre and had a cotton gin.[23] A traveler of 1808 reported that Bruin had recently sold "Bruinsbury [sic]...together with a claim to about three thousand acres of the surrounding land to Messrs. Evans and Overaker of Natchez, reserving to himself his house, offices and garden. It is a mile below the mouth of bayau Pierre, the banks of which being low and swampy, and always annually overflowed in the spring, he projected the intended town of Bruinsbury, where there was a tolerably high bank and a good landing which has only been productive of a cotton gin, a tavern, and an overseer's house for Mr. Evans' plantation, exclusive of the judge's own dwelling house, and it will probably never now become a town notwithstanding many town lots were purchased, as Mr. Evans means to plant all the unappropriated lots, preferring the produce in cotton to the produce in houses."[24][25] There was a cotton gin and farmland at Bruinsburg in 1822, when two boatmen stopped there on the way down from Cincinnati. One of the boatmen recorded in his journal, "...after some enquiry we got lodging with one Mr. Foot who appeared to have the charge of a cotton gin owned by Evans at a settlement called Bruinsburg. Foot informed me that Judge Bruins the former owner of the farm had laid out considerable of a town here & sold the lots at auction but the purchasers neglecting to enter their claims it returned back to the proprietor who sold it to the present owner & purchased a farm adjacent. Met three Boats going up the Buyo [bayou] loaded with various kinds of provision such as, flour, lard, butter, corn, venison, potatoes, pork, &c."[26] One "R Brasher...quite hearty & rugged" lived "near Bruinsburgh at the mouth of Buyo Pierre..." at that time.[27] In 1841, Rice C. Ballard was the trustee selling the 2,300-acre Bruinsburg plantation in Claiborne County and the enslaved people who worked the land in order "to pay three promissory notes" that were owed Rowan & Harris, a major slave-trading firm in Natchez.[28] By 1848 it was noted in a river guide for steamboat people as only a "small place, on the lower side of Bayou Pierre."[29] The plantation and the enslaved families who lived there upon were listed for auction again in 1850.[30] According to the 1890 Port Gibson history, Bruinsburg had "relapsed into a semi-wilderness long before the civil war."[18] Bruinsburg was never incorporated.[19] American Civil WarAccording to Henry Watkins Allen, the Confederate governor of Louisiana, at the time of the civil war, Bruinsburg was more plantation than settlement. He commented, "All estates in the South have names given them, for the convenience of marking cotton bales; also, I suppose, from a feeling of pride in the landowners, being a remnant of Anglo-Saxon customs, Bruinsburg belonged to the Evans' estate, a family whose ancestor had not been undistinguished in the war of 1814."[31] Union Army General Ulysses S. Grant was planning a massive assault on the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi. After having failed to land his army at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, he arrived on April 29, 1863, at Disharoon's Plantation in Louisiana, about 5 mi (8.0 km) north of Bruinsburg on the opposite bank of the Mississippi River.[32] Grant made a plan to land his troops at Rodney, Mississippi, about 12 mi (19 km) downstream, until late that night, an escaped slave (described in the records as an "intelligent contraband") told Grant about the much nearer port of Bruinsburg, which had an excellent steamboat landing, and a good road ascending the bluffs east of the river.[33] The following day, April 30, 1863, Union soldiers began landing at Bruinsburg, marking the beginning of the Battle of Port Gibson, part of the larger Vicksburg Campaign. Because river traffic had diminished through the war, when the soldiers arrived at Bruinsburg the port was nearly deserted, and, according to historian Warren Grabau, the sole witness was one of Grant's scouts, who promptly explained the route inland to Port Gibson and informed the commanding generals that "there were no Rebels anywhere" in the immediate vicinity.[34] The port proved to have a good solid bank, and space for many boats. The U.S. Army moved 22,000 troops, provisions, and artillery across the Mississippi River in approximately 24 hours.[35] The landing at Bruinsburg stood as the largest amphibious operation in American military history for 79 more years, until the 1942 landings in North Africa surpassed Grant's record.[36]

20th and 21st centuries After beginning its history in the 18th and early 19th centuries as an important marketplace, Bruinsburg began to decline, "superseded by Vicksburg and Natchez as a port and gradually abandoned even by neighboring planters."[38] There was still a boat landing and a post office at Bruinsburg circa 1913.[39] In the first few years of the 20th century "several dozen families lived in the Judge's burg, and buildings included not only houses but also a church, school and post office."[19] Eudora Welty wrote about the place in Some Notes on River Country, first published in 1944: "Two miles beyond, at the end of a dim jungle track where you can walk, is the river, immensely wide and vacant, its bluff occupied sometimes by a casual camp of fishermen under the willow trees, where dirty children playing about and nets drying have a look of timeless roaming and poverty and sameness....Go till you find the hazy shore where the Bayou Pierre, dividing in two, reaches around the swamp to meet the river. It is a gray-green land, softly flowered, hung with stillness, Houseboats will be tied there among the cypresses under falls of long moss, all of a color. Aaron Burr's 'flotilla' tied up there, too, for this is Bruinsburg Landing, where the boats were seized one wild day of apprehension. Bruinsburg grew to be a rich, gay place in cotton days. It is almost as if a wand had turned a noisy cotton port into a handful of shanty boats. Yet Bruinsburg Landing has not vanished: it is this."[40] There was still one derelict building standing on pilings at Bruinsburg in the 1980s, and "a metal sign nailed to a tree, but growth had covered all but the word Bruins."[19] The former town and its landing are now located on private property. A historic plaque commemorating Bruinsburg is located on Church Street in Port Gibson.[2][41][42] References

Sources

Information related to Bruinsburg, Mississippi |

||||||||||||||||||||||||