British U-class submarine

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

South Korean TV series Beasts of AsiaHangul비스트 오브 아시아Revised RomanizationBiseuteu Obeu Asia GenreChildren's television seriesWritten byKim Mi-ranStarringAn Jin-hyeon (S1)Jang Mun-ik (S1)Lee Kyoung-yoon (S1)Kim Min-seo (S2)Country of originSouth KoreaOriginal languageKoreanNo. of seasons2No. of episodes12ProductionProducerJeong Hyun-sukRunning time20 minutesOriginal releaseNetworkEducational Broadcasting SystemReleaseJune 20, 2021 (2021-06-20) –October 19, 2022 ...

NOTAM Notice To Airmen atau NOTAM atau Warta Kepada Udarawan atau Wartadara adalah pemberitahuan yang disebarluaskan melalui peralatan telekomunikasi yang berisi informasi mengenai penetapan, kondisi atau perubahan di setiap fasilitas aeronautika, pelayanan, prosedur atau kondisi berbahaya, berjangka waktu pendek dan bersifat penting untuk diketahui oleh personel operasi penerbangan.[1] Tujuan penerbitan NOTAM adalah untuk mencapai tujuan informasi penerbangan dalam upaya menjamin kel...

Об экономическом термине см. Первородный грех (экономика). ХристианствоБиблия Ветхий Завет Новый Завет Евангелие Десять заповедей Нагорная проповедь Апокрифы Бог, Троица Бог Отец Иисус Христос Святой Дух История христианства Апостолы Хронология христианства Ран�...

2008 2015 (départementales) Élections cantonales de 2011 en Seine-et-Marne 23 des 43 cantons de Seine-et-Marne 20 et 27 mars 2011 Type d’élection Élections cantonales PS – Vincent Eblé Majorité départementale PSDVGPCFEELVParti de gauche Sièges obtenus 23 UMP Opposition départementale UMPDVD Sièges obtenus 20 PCF : 1 siège PS : 19 sièges DVD : 6 sièges UMP : 9 sièges Président du Conseil général Sortant Élu Vincent Eblé PS Vincent...

Archaeological artefacts The replicas of the Golden Horns of Gallehus exhibited at the National Museum of Denmark This article contains runic characters. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of runes. The Golden Horns of Gallehus were two horns made of sheet gold, discovered in Gallehus, north of Møgeltønder in Southern Jutland, Denmark.[1] The horns dated to the early 5th century, i.e. the beginning of the Germanic Iron A...

RI Teluk Langsa sekitar 1960an Sejarah Amerika Serikat Nama LST-1128Pembangun Chicago Bridge and Iron Company, SenecaPasang lunas 23 November 1944Diluncurkan 19 Februari 1945Sponsor Nyonya. Marie StaatMulai berlayar 9 Maret 1945Dipensiunkan 29 Juli 1946 Ganti nama Solano County, 1 Juli 1955 Asal nama Solano CountyDicoret 1 November 1958Identifikasi Nomor lambung: LST-1128 Tanda panggil: NBOB[1] Nasib Ditransfer ke Indonesia, 1960 Indonesia Nama Teluk LangsaAsal nama Teluk LangsaDiper...

School in AustraliaNewcastle High SchoolLocation160–200 Parkway Avenue, Hamilton South,Hunter Region, New South WalesAustraliaCoordinates32°55′56″S 151°45′28″E / 32.9322°S 151.7578°E / -32.9322; 151.7578InformationFormer nameNewcastle Girls' High SchoolTypeGovernment-funded co-educational comprehensive secondary day schoolMottoLatin: Remis Velisque(With Oars and Sails; with all one's might[1][2])Established1929; 95 years ago&...

Abraham Lincoln AssociationFormation1908 (as the Lincoln Centennial Association)Typenonprofit, member-supportedHeadquartersSpringfield, Illinois, USAPresidentMichael BurlingameMain organBoard of DirectorsWebsiteabrahamlincolnassociation.org The Abraham Lincoln Association (ALA) is an American association advancing studies on Abraham Lincoln and disseminating scholarship about Lincoln.[1] The ALA was founded in 1908 to lead a national celebration of Lincoln's 100th birthday and continu...

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府...

Carl Reinhold Sahlberg. Potret karya Johan Erik Lindh pada 1839 Carl Reinhold Sahlberg (22 Januari 1779 – 18 Oktober 1860) adalah seorang naturalis Finlandia, yang utamanya menjadi entomologis yang mengkhususkan diri pada kumbang. Pada 1818, Carl Reinhold Sahlberg menggantikan Carl Niclas Hellenius sebagai profesor ekonomi dan sejarah alam di satu-satunya universitas di Finlandia pada masa itu di Turku (Åbo), Akademi Åbo. Referensi Pranala luar Wikimedia Commons memiliki med...

Genus of bird AlcaTemporal range: Miocene - Recent Razorbill (Alca torda) Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Family: Alcidae Tribe: Alcini Genus: AlcaLinnaeus, 1758 Species Alca torda †Alca ausonia †Alca carolinensis †Alca grandis †Alca minor †Alca olsoni †Alca stewarti Alca is a genus of charadriiform bird that contains a single extant species, the razorbill (Alca torda). Many fossil species are known,...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Malta Aviation Museum – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Malta Aviation MuseumMalta Aviation Museum entrance (2015)Established1994LocationTa'Qali, MaltaCoordinates35°53′37″N 14°24′58″E&...

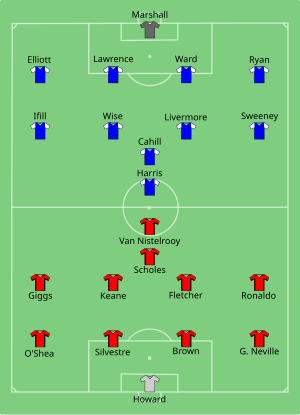

Association football championship match between Manchester United and Millwall, held in 2004 For the women's event, see 2004 FA Women's Cup final. Football match2004 FA Cup FinalEvent2003–04 FA Cup Manchester United Millwall 3 0 Date22 May 2004VenueMillennium Stadium, CardiffMan of the MatchRuud van Nistelrooy (Manchester United)[1]RefereeJeff Winter (North Yorkshire)Attendance71,350WeatherScattered clouds13 °C (55 °F)54% humidity[2]← 2003 2005 → The ...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (يوليو 2023) لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع باري (توضيح). باري النوع مسلسل كوميدي [لغات أخرى] تأليف بيل هادر، &...

This article is about the municipality in Portugal. For the civil parish, see Loures (parish). For the village in Greece, see Loures, Heraklion. For the municipality in France, see Loures-Barousse. Municipality in Lisbon, PortugalLoures, PortugalMunicipality FlagCoat of armsCoordinates: 38°50′N 9°10′W / 38.833°N 9.167°W / 38.833; -9.167Country PortugalRegionLisbonMetropolitan areaLisbonDistrictLisbonParishes10Government • PresidentBernardino So...

Ritratto di Elisabetta di ValoisAutoreSofonisba Anguissola (attribuzione) Data1561 -1565 Tecnicaolio su tela Dimensioni205×123 cm UbicazioneMuseo del Prado, Madrid Il ritratto di Elisabetta di Valois è un dipinto a olio su tela della pittrice Sofonisba Anguissola, databile 1561-1565 circa e conservato nel Museo del Prado a Madrid. Indice 1 Descrizione 2 Note 3 Bibliografia 3.1 Elisabetta di Valois nel mito 3.2 Sofonisba Anguissola 4 Voci correlate 5 Altri progetti Descrizione Elisabett...

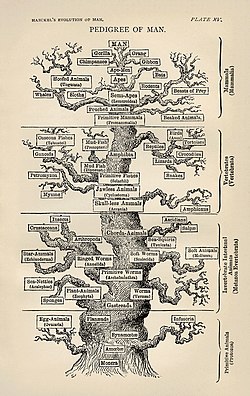

Artikel atau sebagian dari artikel ini mungkin diterjemahkan dari History of evolutionary thought di en.wikipedia.org. Isinya masih belum akurat, karena bagian yang diterjemahkan masih perlu diperhalus dan disempurnakan. Jika Anda menguasai bahasa aslinya, harap pertimbangkan untuk menelusuri referensinya dan menyempurnakan terjemahan ini. Anda juga dapat ikut bergotong royong pada ProyekWiki Perbaikan Terjemahan. (Pesan ini dapat dihapus jika terjemahan dirasa sudah cukup tepat. Lihat pula: ...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (ديسمبر 2018) ترافكو جروبترافكوالشعارمعلومات عامةالبلد مصر التأسيس 1979النوع خاصةالمقر الرئيسي مدينة 6 أكتوبر، مصر�...

William Odling William Odling, FRS (5 September 1829 di Southwark, London – 17 February 1921 di Oxford) adalah seorang kimiawan Inggris yang berkontribusi pada pengembangan tabel periodik. Pada tahun 1860-an Odling, seperti kimiawan kebanyakan saat itu, sedang mengerjakan tabel unsur periodik. Dia tergelitik oleh berat atom dan keterjadian periodik sifat kimia. William Odling dan Julius Lothar Meyer membuat tabel yang serupa, namun dengan perbaikan, dengan tabel asli Mendeleev. Odling menyu...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Gulfport. Cet article est une ébauche concernant une localité de Floride. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. GulfportLa faculté de droit de l'université Stetson.GéographiePays États-UnisÉtat FlorideComté comté de PinellasSuperficie 10,07 km2 (2010)Surface en eau 29,03 %Altitude 5 mCoordonnées 27° 45′ 02″ N, 82° 42�...