Brahmagupta's interpolation formula

|

Read other articles:

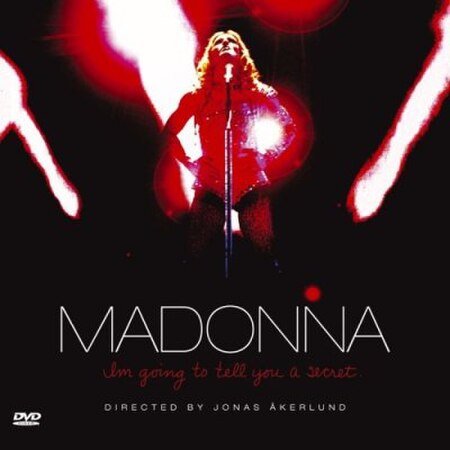

I'm Going to Tell You a SecretAlbum live karya MadonnaDirilis20 Juni 2006Direkam2004GenreLive, Soundtrack, Pop, Dance, ElectronicaDurasi65:59 (album)127:35 (dokumenter)LabelWarner Bros., Warner Music VisionKronologi Madonna Confessions on a Dance Floor(2005)Confessions on a Dance Floor2005 I'm Going to Tell You a Secret (2006) The Confessions Tour (2007)The Confessions Tour2007 I'm Going to Tell You a Secret adalah album live pertama karya penyanyi pop berkebangsaan Amerika Serikat Madonn...

Swiss watch manufacturer For other uses, see Tissot (disambiguation). Tissot SATissot's headquarters in Le Locle, SwitzerlandCompany typeSubsidiaryIndustryWatchmakingFounded1853; 171 years ago (1853)FoundersCharles-Félicien TissotCharles-Emile TissotHeadquartersLe Locle, SwitzerlandArea served150 countriesKey peopleSylvain Dolla (CEO)Georges Nicolas Hayek Jr. (chairman of the board)ProductsWatches, timing devices and systemsRevenue€1.0 billion (2017)Number of employe...

Vista della piazza Mohamed-Bouazizi nel XIV arrondissement di Parigi, inaugurata il 30 giugno 2011 in memoria del giovane tunisino Mohamed Bouazizi, immolatosi il 17 dicembre 2010, inizio simbolico della rivoluzione nel suo paese e in vari paesi del Nord Africa Targa della piazza Mohamed-Bouazizi a Parigi Mohamed Bouazizi (in arabo محمد البوعزيزي?, vero nome Tarek; Sidi Bouzid, 29 marzo 1984 – Ben Arous, 4 gennaio 2011) è stato un attivista tunisino, divenuto simbo...

Wakil Menteri Pertanian IndonesiaLambang Kementerian PertanianBendera Kementerian PertanianPetahanaHarvick Hasnul Qolbisejak 23 Desember 2020Ditunjuk olehPresiden IndonesiaPejabat perdanaSaksonoDibentuk12 Maret 1946 Berikut adalah daftar orang yang pernah menjabat sebagai Wakil Menteri Pertanian atau Menteri Muda Pertanian Indonesia. No Foto Nama Kabinet Menteri Pertanian Dari Sampai Keterangan 1 Saksono Sjahrir II Zainuddin Rasad 12 Maret 1946 2 Oktober 1946 [ket. 1] 2 Sjech Mar...

Doctor and scientist (1863-1946) Simon FlexnerForMemRS1st Director of Rockefeller InstituteIn office1901–1935Succeeded byHerbert Spencer Gasser Personal detailsBorn(1863-03-25)March 25, 1863Louisville, Kentucky, USDiedMay 2, 1946(1946-05-02) (aged 83)New York City, USEducationUniversity of LouisvilleAwardsCameron Prize of the University of Edinburgh (1911)Scientific careerFieldsPhysician, medical educator, and experimental pathologistInstitutionsJohns Hopkins UniversityRockefeller ...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (janvier 2016). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? C...

Highway in Maryland Interstate 195Metropolitan BoulevardI-195 highlighted in redRoute informationAuxiliary route of I-95Maintained by MDSHALength4.35 mi[1][2] (7.00 km)Existed1990–presentNHSEntire routeRestrictionsNo trucks east of exit 1AMajor junctionsWest end MD 166 in ArbutusMajor intersections I-95 in Arbutus US 1 in Arbutus MD 295 in Linthicum East end MD 170 in Linthicum LocationCountryUnited StatesStateMarylandCountiesBaltimore, Ann...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Architecture built by the Khmers during the Angkor period The 12th-century temple of Angkor Wat is the masterpiece of Angkorian architecture. Constructed under the direction of the Khmer king Suryavarman II, Angkor Wat is a Hindu-Buddhist temple. Part of a series on theCulture of Cambodia Society Khmers Ethnic groups Folklore History Languages Holidays Religion Script Women Youth Topics Art Architecture Ceramics Cinema Clothing Cuisine (Royal cuisine) Dance Literature Media Newspapers Radio T...

1971 film The TouchDirected byIngmar BergmanWritten byIngmar BergmanProduced byLars-Owe CarlbergIngmar BergmanStarringElliott GouldBibi AnderssonMax von SydowSheila ReidCinematographySven NykvistProductioncompaniesABC PicturesCinematograph A.B.[1]Distributed byCinerama Releasing Corporation[1]Release date 30 August 1971 (1971-08-30) Running time112 minutesCountriesSwedenUnited StatesLanguageEnglishBudget$1,200,000[2]Box office$1,135,000[2] The To...

Painting by Jean Ranc The Family of Felipe VArtistJean RancYear1723MediumOil on canvasDimensions44 cm × 65 cm (17 in × 26 in)LocationMuseo del Prado, Madrid The Family of Felipe V is an oil on canvas painting by the French artist Jean Ranc completed in 1723. It features depictions of Philip V of Spain and his family. The painting is one of a trio of paintings that bear the same name; the other two are by Louis Michel van Loo and are dated 1738 and (...

此條目翻譯品質不佳。翻譯者可能不熟悉中文或原文語言,也可能使用了機器翻譯。請協助翻譯本條目或重新編寫,并注意避免翻译腔的问题。明顯拙劣的翻譯請改掛{{d|G13}}提交刪除。 「希拉克」重定向至此。關於法国洛泽尔省的同名市镇,請見「希拉克 (洛泽尔省)」。 雅克·勒内·希拉克Jacques René Chirac 第22任法國總統安道爾大公任期1995年5月17日—2007年5月16日...

Supreme Court of the United States38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W / 38.89056; -77.00444EstablishedMarch 4, 1789; 235 years ago (1789-03-04)LocationWashington, D.C.Coordinates38°53′26″N 77°00′16″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W / 38.89056; -77.00444Composition methodPresidential nomination with Senate confirmationAuthorized byConstitution of the United States, Art. III, § 1Judge term lengthl...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会波兰代表團波兰国旗IOC編碼POLNOC波蘭奧林匹克委員會網站olimpijski.pl(英文)(波兰文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員206參賽項目24个大项旗手开幕式:帕维尔·科热尼奥夫斯基(游泳)和马娅·沃什乔夫斯卡(自行车)[1]闭幕式:卡罗利娜·纳亚(皮划艇)&#...

Cet article contient des informations à propos d'un film programmé ou prévu. Il est susceptible de contenir des informations spéculatives et son contenu peut être nettement modifié au fur et à mesure de l'avancement du film et des informations disponibles s'y rapportant. → La dernière modification de cette page a été faite le 16 mai 2024 à 18:09. Fables mortelles Données clés Réalisation Delphine Lemoine Scénario Julien Capron Acteurs principaux Elsa LunghiniClém...

عبد الرحمن الخازني معلومات شخصية الميلاد 1115مإيران تاريخ الوفاة 1155م مواطنة الدولة السلجوقية الحياة العملية أعمال اختراع الآلات العلمية، والساعة المائية مشرف الدكتوراه عمر الخيام تعلم لدى عمر الخيام، والمظفر الاسفزاري المهنة عالم مسلم مجال العمل الفلسفة...

American diplomat (1870–1959) Ulysses S. Grant-SmithUnited States Minister to Uruguay In officeJuly 13, 1925 – January 11, 1929PresidentCalvin CoolidgePreceded byHerman Hoffman PhilipSucceeded byLeland B. Harrison1st United States Minister to Albania In officeDecember 4, 1922 – February 8, 1925PresidentWarren G. Harding Calvin CoolidgePreceded byDiplomatic relations establishedSucceeded byCharles C. Hart Personal detailsBorn(1870-11-18)November 18, 1870Washington, Penn...

Settlement in Kulai District, Johor, Malaysia This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: FELDA Taib Andak – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) FELDA Taib Andak FELDA Taib Andak or Kampung Taib Andak is a settlement in Kulai District, Johor, Malaysia. It ...

Protest against communist Polish government Poznań JunePart of the Cold WarThe sign reads We demand bread!Date28–30 June 1956 (1956-06-28 – 1956-06-30)LocationPoznań, Polish People's RepublicResult Protests suppressedBelligerents Protesters Polish People's ArmyInternal Security CorpsSłużba BezpieczeństwaStrength 100,000[1] 10,000390 tanks[1]Casualties and losses 57–100 killed600 wounded[2] 8 killed[3] The 1956 Poznań protests, al...