Book of Taliesin

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Afriansyah Noor Wakil Menteri Ketenagakerjaan ke-2PetahanaMulai menjabat 15 Juni 2022PresidenJoko WidodomenteriIda Fauziyah PendahuluWilopoPenggantiPetahana Informasi pribadiLahir20 April 1972 (umur 51)JambiPartai politikPBBSuami/istriLin NurhayaniHubunganSidi Tando (kakek)Anak4Alma materInstitut Sains dan Teknologi NasionalSekolah Tinggi Ilmu Administrasi Mandala IndonesiaPekerjaanPolitikusSunting kotak info • L • B Ir. Afriansyah Noor, M.Si, IPU. (lahir 20 April 1...

Prison FightStatusAktifTujuanRehabilitasi narapidana[1]Kantor pusatBangkok, Thailand[2]Tokoh pentingKirill Sokur,[3]Aree Chaloisuk[4]Departemen Pemasyarakatan Thailand[5]Situs webwww.prisonfight.com Prison Fight[2] adalah program rehabilitasi untuk narapidana melalui olahraga tempur yang didirikan pada tahun 2012.[6] Program ini diselenggarakan atas kerja sama dengan Departemen Pemasyarakatan Thailand, sebuah badan dari Kementerian Kehak...

LabolewaDesaNegara IndonesiaProvinsiNusa Tenggara TimurKabupatenNagekeoKecamatanAesesaKode Kemendagri53.16.01.2002 Luas... km²Jumlah penduduk... jiwaKepadatan... jiwa/km² Kampung Adat Kawa. Labolewa adalah desa di kecamatan Aesesa, Kabupaten Nagekeo, Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. Di desa ini terdapat Kampung Adat Kawa, yang merupakan salah satu dari sekian kampung adat yang ada di wilayah kabupaten Nagekeo. Jarak tempuh menuju kampung adat kawa sekitar 5 km dari Kantor Desa Labo...

Largest park in Milpitas, California Ed R. Levin County ParkA view of the Ed R. Levin County Park and Sandy Wool Lake from Agua Caliente TrailEd R. Levin County ParkTypelandscape gardenLocationMilpitas, CaliforniaCoordinates37°28′00″N 121°51′25″W / 37.466604°N 121.856900°W / 37.466604; -121.856900[1]AreaSanta Clara County Parks and Recreation DepartmentOperated bySanta Clara County Parks and Recreation Department Spring Valley Pond Ed R. Levin ...

Papan di Pine Valley, California, Amerika Serikat, sebuah komunitas lepas di timurlaut San Diego. Dalam hukum, sebuah wilayah lepas atau kawasan tak tergabung adalah suatu bagian tanah yang bukan bagian dari kabupaten atau kota manapun di suatu negara. Tergabung dalam hal ini berarti bagian dari sebuah kabupaten atau kota, contoh sebuah kota dengan pemerintahnya sendiri. Dengan demikian, biasanya wilayah lepas tidak menjadi subjek pajak pemerintah kabupaten atau pemerintah kota manapun. Wilay...

Chemical compound Dienestrol diacetateClinical dataTrade namesFaragynol, GynocyrolOther namesDienestrol acetate; LipamoneDrug classNonsteroidal estrogen; Estrogen esterIdentifiers IUPAC name [4-[(2Z,4E)-4-(4-acetyloxyphenyl)hexa-2,4-dien-3-yl]phenyl] acetate CAS Number24705-61-1 YACI: 84-19-5 YPubChem CID24884313DrugBankDB14668ChemSpider4707742UNIID20D148WPQACI: D20D148WPQ YChEMBLChEMBL3188355CompTox Dashboard (EPA)DTXSID9057840 Chemical and physical dataFormulaC22H22...

Alam SuteraDistrik Bisnis Pusat Alam Sutera dilihat dari Jalan Tol Lingkar Luar Jakarta 2LokasiKota Tangerang dan Tangerang Selatan, BantenStatusSelesaiPerusahaanPengembangAlam Sutera RealtyPemilikAlam Sutera RealtyRincian teknisUkuran lahan800 hektar Alam Sutera adalah sebuah kota terencana yang dikembangkan oleh Alam Sutera Realty di Kota Tangerang dan Tangerang Selatan, Banten, Indonesia. Alam Sutera terletak di tenggara Jakarta dan berada di dalam kawasan metropolitan Jabodetabek. Alam Su...

Запрос «Гусь» перенаправляется сюда; для терминов «Гусь» и «Гуси» см. также другие значения. Гуси Домашний гусь (Эмденский) Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:Хордовы...

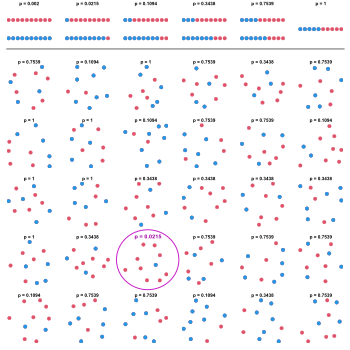

Statistical interpretation with many tests An example of coincidence produced by data dredging (uncorrected multiple comparisions) showing a correlation between the number of letters in a spelling bee's winning word and the number of people in the United States killed by venomous spiders. Given a large enough pool of variables for the same time period, it is possible to find a pair of graphs that show a spurious correlation. In statistics, the multiple comparisons, multiplicity or multiple te...

Election in Washington Main article: 1940 United States presidential election 1940 United States presidential election in Washington (state) ← 1936 November 5, 1940[1] 1944 → All 8 Washington votes to the Electoral College Nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt Wendell Willkie Party Democratic Republican Home state New York New York Running mate Henry A. Wallace Charles L. McNary Electoral vote 8 0 Popular vote 462,145 322,123 Percentage 58.22% ...

Grand Prix Australia 2000 Lomba ke-1 dari 17 dalam Formula Satu musim 2000← Lomba sebelumnyaLomba berikutnya → Detail perlombaanTanggal 12 Maret 2000 (2000-03-12)Nama resmi 2000 Qantas Australian Grand PrixLokasi Sirkuit Grand Prix Melbourne, Melbourne, AustraliaSirkuit Sirkuit jalan raya sementaraPanjang sirkuit 5.503 km (3.295 mi)Cuaca CerahPosisi polePembalap Mika Häkkinen McLaren-MercedesWaktu 1:30.556Putaran tercepatPembalap Rubens Barrichello FerrariWaktu 1...

غانيشا (بالسنسكريتية: गणेश) معلومات شخصية تاريخ الميلاد 2000 ق.م الوفاة 1000 ق.مالهند عدد الأولاد 2 الأب شيفا الأم بارفاتي إخوة وأخوات كارتيكيا تعديل مصدري - تعديل غانيشا (بالإنجليزية: Ganesha، بالسنسكريتية: गणेश)، يُعرف أيضًا باسم غاناباتي وفيناياكا�...

1981 filmSay a Word for the Poor HussarDirected byEldar RyazanovWritten byEldar RyazanovGrigori GorinProduced byBoris KrishtulStarringStanislav SadalskiyOleg BasilashviliValentin Gaft Yevgeny LeonovNarrated byAndrei MironovCinematographyVladimir NakhabtsevMusic byAndrey Petrov[1]ProductioncompanyMosfilmRelease date January 1981 (1981-01) Running time167 minutesCountrySoviet UnionLanguageRussian Say a Word for the Poor Hussar[2] (Russian: О бедном гусаре ...

Chemical compound Calcium carbonate Calcium, Ca Carbon, C Oxygen, O Names IUPAC name Calcium carbonate Other names AragoniteCalciteChalkLimeLimestoneMarbleOystershellPearl Identifiers CAS Number 471-34-1 Y 3D model (JSmol) Interactive imageInteractive image ChEBI CHEBI:3311 Y ChEMBL ChEMBL1200539 N ChemSpider 9708 Y DrugBank DB06724 ECHA InfoCard 100.006.765 EC Number 207-439-9 E number E170 (colours) KEGG D00932 Y PubChem CID 10112 R...

After EarthPoster bioskopSutradaraM. Night ShyamalanProduserCaleeb PinkettJada Pinkett SmithWill SmithJames LassiterSkenarioGary WhittaM. Night ShyamalanCeritaWill SmithPemeranWill SmithJaden SmithPenata musikJames Newton HowardSinematograferPeter SuschitzkyPenyuntingSteven RosenblumPerusahaanproduksiOverbrook EntertainmentBlinding Edge PicturesRelativity MediaDistributorColumbia PicturesTanggal rilis 31 Mei 2013 (2013-05-31) Durasi100 menit[1]NegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaIng...

نصف المحور الأكبر (a) والأصغر (b) لقطع ناقص المحور الرئيسي في القطع الناقص هو القطر الأكبر والذي يمر في مركزه وبؤرتيه وينتهي على أوسع نقطة على محيط القطع. هكذا فإن نصف المحور الرئيسي (أو نصف المحور الأكبر) هو أحد نصفي المحور الرئيسي بحيث يبدأ من المركز مارا في أحد بؤرتيه منتهيا...

Former constellation Sceptrum et Manus Iustitiae constellation Sceptrum et Manus Iustitiae (Latin for scepter and hand of justice) was a constellation created by Augustin Royer in 1679 to honor king Louis XIV of France. It was formed from stars of what is today the constellations Lacerta and western Andromeda. Due to the awkward name the constellation was modified and name changed a couple of times, for example some old star maps show Sceptrum Imperiale, Stellio and Scettro, and Johannes Heve...

Czech tennis player Mandlikova redirects here. For the surname, see Mandlik. Hana MandlíkováMandlíková in 2009Country (sports) Czechoslovakia AustraliaResidencePrague, Czech Republic & Bradenton, FloridaBorn (1962-02-19) 19 February 1962 (age 62)Prague, CzechoslovakiaHeight1.73 m (5 ft 8 in)Turned pro1978Retired1990PlaysRight-handed (one handed-backhand)Prize money$3,340,959Int. Tennis HoF1994 (member page)SinglesCareer record565–194Caree...

This article is about the 1917 battle. For other battles of the Aisne, see Battle of the Aisne. Battle of the First World War Second Battle of the AisnePart of the Western Front of the First World WarChemin des Dames and Champagne, 1917Date16 April – 9 May, 24–26 October 1917LocationBetween Soissons and Reims, France49°24′N 3°36′E / 49.400°N 3.600°E / 49.400; 3.600Result InconclusiveBelligerents France Russia GermanyCommanders and leaders ...

Village in Denbighshire, Wales Human settlement in WalesTremeirchionThe Salusbury Arms public house, TremeirchionTremeirchionLocation within DenbighshirePopulation703 (Parish)1,649 (Ward)[1](2011 Census)OS grid referenceSJ081729• Cardiff121 mi (195 km)• London178 mi (286 km)CommunityTremeirchionPrincipal areaDenbighshirePreserved countyClwydCountryWalesSovereign stateUnited KingdomPost townST. ASAPHPostcode districtL...