Black Death in Italy

|

Read other articles:

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento ingegneria è priva o carente di note e riferimenti bibliografici puntuali. Sebbene vi siano una bibliografia e/o dei collegamenti esterni, manca la contestualizzazione delle fonti con note a piè di pagina o altri riferimenti precisi che indichino puntualmente la provenienza delle informazioni. Puoi migliorare questa voce citando le fonti più precisamente. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Flusso turbolento dell'acqua in un fiume In...

Gaya atau nada penulisan artikel ini tidak mengikuti gaya dan nada penulisan ensiklopedis yang diberlakukan di Wikipedia. Bantulah memperbaikinya berdasarkan panduan penulisan artikel. (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Air Terjun Tumpak SewuAir Terjun Tumpak SewuLokasiSidomulyo, Pronojiwo, Lumajang, Jawa Timur, IndonesiaKoordinat8°13′49″S 112°55′01″E / 8.230408°S 112.916939°E / -8.230408; 112.916939Koordinat: 8°13′49″S...

Federasi Sepak Bola TahitiOFCDidirikan1989Kantor pusatPiraeBergabung dengan FIFA1990Bergabung dengan OFC1990PresidenHenri Ariiotima[1]Websitehttp://www.ftf.pf Federasi Sepak Bola Tahiti (Prancis: Fédération tahitienne de footballcode: fr is deprecated ), adalah badan pengendali sepak bola di Polinesia Prancis. Kompetisi Badan ini menyelenggarakan beberapa kompetisi di Tahiti, yakni: Ligue 1 Tahiti Ligue 2 Tahiti Piala Tahiti Piala Super Tahiti Tim nasional Badan ini juga merupakan b...

Painting by Rembrandt The Preacher Eleazar SwalmiusArtistRembrandtYear1637MediumOil on canvasDimensions132 cm × 109 cm (51+9⁄6 in × 42.9 in)LocationRoyal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Antwerp The Preacher Eleazar Swalmius is a 1637 oil-on-canvas painting by the Dutch artist Rembrandt. It is currently owned by the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp.[1] The painting has been certified a real Rembrandt.[2][3][4] T...

Ministry of CultureBadr bin Abdullah Al Saud, the current Minister of Culture since 2018Agency overviewFormedJune 2, 2018; 5 years ago (2018-06-02)JurisdictionGovernment of Saudi ArabiaHeadquartersRiyadh, Saudi ArabiaAgency executiveBadr bin Farhan Al Saud, MinisterWebsiteOfficial English Website The Ministry of Culture (MoC; Arabic: وزارة الثقافة) is a governmental organization in Saudi Arabia was established in June 2018 and responsible for various aspects of ...

Richard J. Codey ArenaCodey ArenaThe Richard J. Codey Arena with the Turtle Back Zoo entrance arch.Former namesSouth Mountain Arena (1958–2004)LocationWest Orange, New JerseyCoordinates40°46′8″N 74°16′55″W / 40.76889°N 74.28194°W / 40.76889; -74.28194Public transit NJT Bus: 73 Community Coach Bus: 77 OurBus: Livingston/West OrangeOwnerEssex County Department of Parks and RecreationCapacity2,500 (Rink 1), 500 (Rink 2)SurfaceIce, Floor (Rink 1 can be co...

Questa voce sugli argomenti storia della Germania e province scomparse è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Nuova SlesiaLa Nuova Slesia tra i territori polacchi annessi dalla Prussia durante la Terza spartizione della Polonia in azzurro Informazioni generaliNome ufficiale(DE) Neuschlesien(PL) Nowy Śląsk Nome completoNuova Slesia CapoluogoSiewierz Superficie2230 km² (1796) Popolazione76634 (1796) Dipendente da Regno di Prussia Evoluz...

Ancient Egyptian script This article is about the Egyptian script. For the later phase of the Egyptian language, see Egyptian language § Demotic. DemoticDemotic script on a Rosetta Stone replicaScript type Logographic with consonantsTime periodc. 650 BC – 5th century ADDirectionRight-to-leftLanguagesEgyptian language (Demotic)Related scriptsParent systemsEgyptian hieroglyphsHieraticDemoticChild systemsMeroitic, Coptic (influenced)ISO 15924ISO 15924Egyd (070), Egyptian dem...

CityBaqa-Jatt באקה-ג'תباقة جتّCityHebrew transcription(s) • Also spelledBaqa-Jat (official)A residential area in Baqa al-GharbiyyeBaqa-JattShow map of Haifa region of IsraelBaqa-JattShow map of IsraelCoordinates: 32°24′59.22″N 35°2′53.87″E / 32.4164500°N 35.0482972°E / 32.4164500; 35.0482972District HaifaArea • Total16,392 dunams (16.392 km2 or 6.329 sq mi) Baqa-Jatt was an Israeli...

County in Kansas, United States Not to be confused with Coffeyville, Kansas. County in KansasCoffey CountyCountyBurlington Carnegie Free Library (2016)Location within the U.S. state of KansasKansas's location within the U.S.Coordinates: 38°14′N 95°44′W / 38.233°N 95.733°W / 38.233; -95.733Country United StatesState KansasFoundedAugust 25, 1855Named forAsbury M. CoffeySeatBurlingtonLargest cityBurlingtonArea • Total654 sq mi (1,69...

У Вікіпедії є статті про інші значення цього терміна: 1830 (значення). Рік: 1827 · 1828 · 1829 — 1830 — 1831 · 1832 · 1833 Десятиліття: 1810-ті · 1820-ті — 1830-ті — 1840-ві · 1850-ті Століття: XVII · XVIII — XIX — XX · XXI Тисячоліття: 1-ше — 2-ге — 3-тє 1830 в інших календар...

Airport in Rechlin, GermanyMüritz AirparkIATA: REBICAO: EDAXSummaryAirport typePublicOperatorEntwicklungs-und Betriebsgesellschaft Müritzflugplatz Rechlin-Lärz mbHLocationRechlin, GermanyElevation AMSL220 ft / 67 mCoordinates53°18′23″N 012°45′11″E / 53.30639°N 12.75306°E / 53.30639; 12.75306Websitemueritz-airpark.deRunways Direction Length Surface ft m 07/25 7,808 2,380 Concrete 14/32 6,170 1,880 Concrete disused Müritz Airpark (IATA: REB...

Mosque in Shusha, Azerbaijan Saatli MosqueThe facade of the mosque after restoration work in 2023ReligionAffiliationIslamLocationLocationShusha, AzerbaijanGeographic coordinates39°45′46″N 46°45′04″E / 39.76278°N 46.75107°E / 39.76278; 46.75107ArchitectureArchitect(s)Karbalayi Safikhan KarabakhiStyleIslamic architectureCompleted1883Minaret(s)2 (one completely destroyed during occupation) Saatli Mosque (Azerbaijani: Saatlı məscidi) is a mosque located in Sh...

2023 British filmBank of DaveDirected byChris FogginWritten byPiers AshworthProduced by Matt Williams Karl Hall Piers Tempest Starring Joel Fry Phoebe Dynevor Rory Kinnear Hugh Bonneville Paul Kaye Jo Hartley Cathy Tyson CinematographyMike Stern SterzynskiEdited byMartina ZamoloMusic byChristian HensonProductioncompanies Tempo Productions Limited Future Artists Entertainment Ingenious Media Rojovid Films Distributed byNetflix William Morris Endeavor (WME) EntertainmentRelease date 16 Ja...

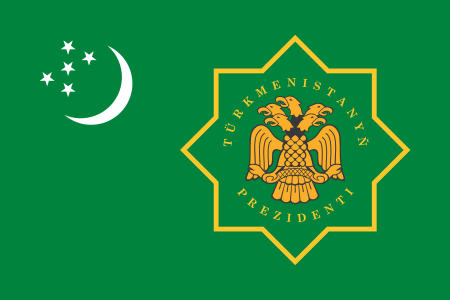

土库曼斯坦总统土库曼斯坦国徽土库曼斯坦总统旗現任谢尔达尔·别尔德穆哈梅多夫自2022年3月19日官邸阿什哈巴德总统府(Oguzkhan Presidential Palace)機關所在地阿什哈巴德任命者直接选举任期7年,可连选连任首任萨帕尔穆拉特·尼亚佐夫设立1991年10月27日 土库曼斯坦土库曼斯坦政府与政治 国家政府 土库曼斯坦宪法 国旗 国徽 国歌 立法機關(英语:National Council of Turkmenistan) ...

ХуторДонецкий лесхоз 49°02′10″ с. ш. 40°32′48″ в. д.HGЯO Страна Россия Субъект Федерации Ростовская область Муниципальный район Миллеровский Сельское поселение Первомайское История и география Часовой пояс UTC+3:00 Население Население 92[1] человека (2010) Цифр�...

العلاقات النمساوية الطاجيكستانية النمسا طاجيكستان النمسا طاجيكستان تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات النمساوية الطاجيكستانية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين النمسا وطاجيكستان.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للد�...

Law enforcement agency of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps This article is about the federal agency. For the U.S. television show, see NCIS (TV series). Not to be confused with National Criminal Intelligence Service. Law enforcement agency United States Naval Criminal Investigative ServiceThe NCIS logoSeal of the Naval Criminal Investigative ServiceBadge of an NCIS Special AgentAbbreviationNCISAgency overviewFormedDecember 14, 1993; 30 years ago (1993-12-14)Preceding agenciesN...

Albaner Shqiptarët Antal sammanlagt 6,5 miljoner Regioner med betydande antal Albanien - 2 312 026 Kosovo (kosovoalbaner) 1 870 981[1] Nordmakedonien 500 000[1] Bosnien och Hercegovina mellan 10 000 och 12 000 Montenegro 31 000 Grekland 600 000[2](se även arvaniter) USA 113 000[3] Turkiet (inklusive) Irakiska Kurdistan 300 000–1 300 000[4][5][6][4][7][8][9] Tyskland 320 000[10][11] Italien 375 000[12](se även arberesj...

American football player and coach (1922–2011) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Don Fambrough – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Don FambroughBiographical detailsBorn(1922-10-19)October 19, 1922Longview, Texas, U.S.DiedSep...