Black Christmas disaster

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

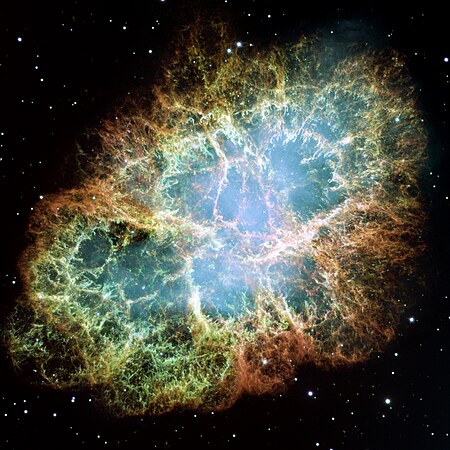

Nebula Kepiting merupakan sisa-sisa dari supernova SN 1054, gambar diambil oleh Teleskop Hubble. SN 1054 adalah supernova yang pertama kali yang diamati pada tanggal 4 Juli 1054, dan tetap terlihat selama dua tahun. Tanggal pasti telah disengketakan tetapi sebagian besar akun menerima tanggal Tiongkok pada 4 Juli. Peristiwa itu direkam dalam sebuah dokumen dari dunia arab, dalam astronomi komtemporer Tiongkok, dan rujukannya juga ditemukan dalam dokumen Jepang kemudian (abad ke 13). Supernova...

Radio station in Columbia, CaliforniaKCVR-FMColumbia, CaliforniaBroadcast areaModesto, CaliforniaFrequency98.9 MHzBrandingFuego 98.9ProgrammingFormatBilingual Rhythmic CHROwnershipOwnerEntravision Communications(Entravision Holdings, LLC)Sister stationsKTSEHistoryFirst air date1995 (as KTDO)Former call signsKAGF (1993-1994)KTDO (1994-2000)KTDZ (2000-2001)Technical informationFacility ID12063ClassAERP6,000 wattsHAAT100 metersTransmitter coordinates38°2′15″N 120°22′5″W / þ...

سديم السرطان كمخلفات نجم منفجر.الصور للضوء المرئي، وصورة للاشعة تحت الحمراء وصورة للأشعة فوق البنفسجية وصور لأشعة أكس ذات أطوال موجة مختلفة تدل على شدة ارتفاع درجة حرارة المصدر، إلتقطتها تلسكوبات مختلفة، كل منها يرى حيز ضيق من طيف الأشعة. المسح الفلكي (بالإنجليزية: Astronomical...

Androni Giocattoli 2017GénéralitésÉquipe GW Shimano-SidermecCode UCI ANSStatut UCI ProTeamPays ItalieSport Cyclisme sur routeEffectif 19Manager général Gianni SavioDirecteurs sportifs Gianni Savio, Antonio Castaño (d), Leonardo Scarselli, Alessandro SpezialettiPalmarèsNombre de victoires 1Androni Giocattoli-Sidermec 2016Androni Giocattoli-Sidermec 2018modifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata La saison 2017 de l'Androni-Sidermerc-Bottecchia est la vingt-deuxième de cette ...

LighthouseCapo Focardo Capo Focardo LighthouseLocationPorto AzzurroElbaItalyCoordinates42°45′16″N 10°24′35″E / 42.754313°N 10.409671°E / 42.754313; 10.409671TowerConstructed1863Foundationmasonry baseConstructionmasonry towerHeight13 metres (43 ft)Shapeoctagonal tower with balcony and lanternMarkingswhite tower, grey metallic lantern domePower sourcemains electricity OperatorMarina Militare[1][2]LightFocal height32 metres (105&#...

Commune in Occitania, FranceMeyrueisCommuneClock tower and bridge over the Béthuzon in Meyrueis Coat of armsLocation of Meyrueis MeyrueisShow map of FranceMeyrueisShow map of OccitanieCoordinates: 44°10′46″N 3°25′49″E / 44.1794°N 3.4303°E / 44.1794; 3.4303CountryFranceRegionOccitaniaDepartmentLozèreArrondissementFloracCantonFlorac Trois RivièresIntercommunalityGorges Causses CévennesGovernment • Mayor (2020–2026) René Jeanjean[1&...

Barium sulfat Model 3D barium sulfat Penanda Nomor CAS 7727-43-7 Y Model 3D (JSmol) Gambar interaktif 3DMet {{{3DMet}}} ChEBI CHEBI:133326 N ChEMBL ChEMBL2105897 N ChemSpider 22823 Y Nomor EC PubChem CID 24414 Nomor RTECS {{{value}}} UNII 25BB7EKE2E Y CompTox Dashboard (EPA) DTXSID0050471 InChI InChI=1S/Ba.H2O4S/c;1-5(2,3)4/h;(H2,1,2,3,4)/q+2;/p-2 YKey: TZCXTZWJZNENPQ-UHFFFAOYSA-L YInChI=1/Ba.H2O4S/c;1-5(2,3)4/h;(H2,1,2,3,4)/q+2;/p-2Key: TZCXTZWJZ...

Place in Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestineal-Qastal القسطلal-Qastal hillEtymology: castellum or castale[1] 1870s map 1940s map modern map 1940s with modern overlay map A series of historical maps of the area around Al-Qastal, Jerusalem (click the buttons)al-QastalLocation within Mandatory PalestineCoordinates: 31°47′44″N 35°8′39″E / 31.79556°N 35.14417°E / 31.79556; 35.14417Palestine grid163/133Geopolitical entityMandatory PalestineSubdistr...

This article is about the group of heritage listed protected areas. For the general mountain range and bioregion, see Australian Alps. Protected area in AustraliaAustralian Alps National Parks and ReservesAustraliaThe Australian Alps viewed from Snowy River Road, near Suggan Buggan, Victoria.Map of the region shaded as listed on the National Heritage List.Australian Alps National Parks and ReservesNearest town or cityCanberraCoordinates37°S 148°E / 37°S 148°E / -37...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

Bobby VintonBobby Vinton nel 1965 Nazionalità Stati Uniti GenerePopRockRock and roll Periodo di attività musicale1961 – in attività Album pubblicati106 Studio38 Live1 Raccolte67 Sito ufficiale Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Stanley Robert Vinton, Jr., detto Bobby (Canonsburg, 16 aprile 1935) è un cantante statunitense di musica pop e rock. Tra le più celebri star della musica statunitense, egli era uno dei cantanti più popolari degli anni cinquanta.&...

Men's singlesat the VII Olympic Winter GamesDates29 January-1 FebruaryCompetitors16 from 11 nationsMedalists Hayes Alan Jenkins United States Ronald Robertson United States David Jenkins United States← 19521960 → Figure skating at the Olympics Figure skating at the1956 Winter OlympicsSinglesmenladiesPairsmixedvte The men's figure skating competition at the 1956 Winter Olympics took place at the Olympic Ice Stadium in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy. Th...

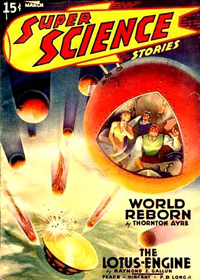

US pulp science fiction magazine Not to be confused with Super-Science Fiction. First issue cover; artist unknown Super Science Stories was an American pulp science fiction magazine published by Popular Publications from 1940 to 1943, and again from 1949 to 1951. Popular launched it under their Fictioneers imprint, which they used for magazines, paying writers less than one cent per word. Frederik Pohl was hired in late 1939, at 19 years old, to edit the magazine; he also edited Astonishing S...

Archaeological research institute Deutsches Archäologisches InstitutLogo of the German Archaeological InstituteFounder(s)Eduard GerhardEstablished1832; 192 years ago (1832)PresidentFriederike FlessBudget€38 million[1]LocationBerlin, Germany Coordinates52°27′38.10″N 13°18′1.27″E / 52.4605833°N 13.3003528°E / 52.4605833; 13.3003528Websitewww.dainst.org The German Archaeological Institute (German: Deutsches Archäologisches Institu...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (ديسمبر 2018) 34° خط عرض 34 جنوب خريطة لجميع الإحداثيات من جوجل خريطة لجميع الإحداثيات من بينغ تصدير جميع الإحداثيات من ك...

Fundação Educacional do Município de Assis - FEMAInstituto Municipal de Ensino Superior de AssisFEMAs hall of entrance from Getúlio Vargas AvenueMottoVocê com atitude. O lugar é aqui.Type city universityEstablished19 October 1985 (1985-10-19)BudgetR$14,330,919[1]PrincipalEduardo Augusto Vella GonçalvesStudents2412[2]Location Assis, State of São Paulo, Brazil22°38′38″S 50°25′17″W / 22.6437862°S 50.4213949°W / -22.64378...

United States Zouave CadetsActive1856–1861Country United StatesAllegiance IllinoisBranchMilitiaTypeZouave infantryRoleFoot guardsSize61 soldiers, 15 musicians (1860)[1]ArmoryGarrett Block (Chicago, Illinois)[2]Nickname(s)Governor's Guard of Illinois[a]MarchZouave Cadets Quickstep (A. J. Vaas)[4]CommandersNotablecommandersElmer EllsworthMilitary unit The United States Zouave Cadets (also known as the Chicago Zouaves and Zouave Cadets of Chicago) was...

UK local election Main article: Burnley Borough Council elections 2021 local election results in Burnley The 2021 Burnley Borough Council election took place on 6 May 2021 to elect members of Burnley Borough Council in England.[1] This election was held on the same day as other local elections. As with many other local elections in England, it was postponed from May 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. One third of the council was up for election, and each successful candidate will ser...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (ديسمبر 2018) بطولة العالم للدراجات على المضمار 1927 التفاصيل التاريخ 1927 الموقع ألمانيا (كولونيا) نوع السباق سباق الد...

1926 United States Supreme Court caseCorrigan et al. v. BuckleySupreme Court of the United StatesArgued January 8, 1926Decided May 24, 1926Full case nameCorrigan et al. v. BuckleyCitations271 U.S. 323 (more)46 S. Ct. 521; 70 L. Ed. 969HoldingThis decision dismissed any constitutional grounds for challenges racially restrictive covenants and upheld the legal right of property owners to enforce these discriminatory agreements.Court membership Chief Justice William H. Taft Associate Justices Ol...