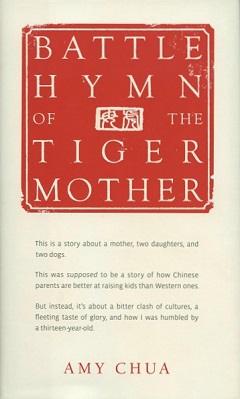

Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Dutch drug dealer Patrick van der EemBornPatrick Paul van der Eem1973Curaçao, Netherlands AntillesNationalityDutchOccupation(s)Drug dealer, writerKnown forPeter R. de Vries undercover videoParentLeon van der Eem Patrick Paul van der Eem (born 1973; Curaçao) is a Dutch Antillean and convicted drug dealer known for his part in the undercover television report about Joran van der Sloot that was produced by Dutch crime reporter Peter R. de Vries.[1] The program set a Dutch televisi...

Kagamino 鏡野町Kota kecil BenderaLambangLokasi Kagamino di Prefektur OkayamaNegara JepangWilayahChūgokuPrefektur OkayamaDistrikTomataLuas • Total420 km2 (160 sq mi)Populasi (Oktober 1, 2015) • Total12.847 • Kepadatan30,59/km2 (7,920/sq mi)Zona waktuUTC+9 (JST)Kode pos708-0392Simbol • PohonFagaceae• BungaGentiana scabra Prunus serrulata• BurungMegaceryle lugubris• Kupu-kupuByasa alcinous Luehdorfia japonica...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Desember 2022. Seorang pengrajin batik sedang membuat batik Batik Malaysia adalah seni tekstil yang berasal dari Malaysia, khususnya di pesisir timur Malaysia (Kelantan, Terengganu dan Pahang). Kebanyakan motif populernya adalah dedaunan dan bunga. Batik Malaysia ya...

Pour les personnes ayant le même patronyme, voir Kavanagh. Niamh Kavanagh Niamh Kavanagh à Oslo le 26 mai 2010.Informations générales Naissance 13 février 1968 (56 ans)Dublin, Leinster Irlande Activité principale Chanteuse Genre musical Pop Instruments Voix Années actives 1990 à aujourd'hui Labels Arista Site officiel http://www.webwrite.net/niamh.htm modifier Niamh Kavanagh est une chanteuse irlandaise née le 13 février 1968 à Dublin. Biographie En 1991, l'artiste chante sur...

Istilah rasul dikenal dalam Islam dan Kristen. Meski demikian, terdapat perbedaan pemahaman mengenai istilah tersebut. Dalam Islam, rasul adalah seorang Nabi dan Rasul yang mendapat wahyu dari Allah SWT, tidak hanya untuk dirinya sendiri namun wajib menyampaikan wahyu yang dia terima kepada umat, rasul terahir yang diutus oleh Allah SWT ialah Nabi Muhammad SAW membawa syariat-syariat baru yang tidak menghapuskan syariat-syariat dari rasul sebelumnya[1]. Berbeda dengan nabi biasa yang ...

Om Puri(OBE)[1]Puri di Festival Film Internasional Toronto 2010LahirOm Rajesh Puri18 Oktober 1950 (umur 73)Ambala, Punjab, IndiaMeninggal6 Januari 2017(2017-01-06) (umur 66)Mumbai, Maharashtra, IndiaSebab meninggalSerangan jantungPekerjaanPemeranTahun aktif1972–2017Suami/istriNandita Puri (m. 1993)PenghargaanPadma Shri, Penghargaan Film Nasional Om Rajesh Puri OBE[1] (18 Oktober 1950 – 6 Januari 2017) adalah seorang pemeran India[2] yang tampil...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Breaza (disambiguasi). BreazaKota Lambang kebesaranLetak BreazaNegara RumaniaProvinsiPrahovaStatusKotaPemerintahan • Wali kotaGeorge Mărăcineanu (Partidul Social Democrat)Populasi (2002) • Total18.863Zona waktuUTC+2 (EET) • Musim panas (DST)UTC+3 (EEST)Situs webhttp://www.primariabreaza.ro/ Breaza (pengucapan bahasa Rumania: [ˈbre̯aza]) adalah kota yang terletak di provinsi Prahova, Rumania. Kota ini memiliki ju...

Shopping mall in Chicago, United StatesChinatown SquareChinatown Square from the LLocationChinatown, Chicago, United StatesCoordinates41°51′14″N 87°37′59″W / 41.85389°N 87.63306°W / 41.85389; -87.63306Address2100 S. Wentworth Ave.Opening date1993DeveloperChinese American Development CorporationArchitectHarry Weese and AssociatesNo. of floors2Public transit access CTA Red at Cermak-ChinatownWebsitewww.chicagochinatown.org Chinatown Square (tradit...

Voce principale: Associazione Calcio Pavia. AC PaviaStagione 1986-1987 Sport calcio Squadra Pavia Allenatore Gianni Bui Presidente Claudio Achilli Serie C22º nel girone B (promosso in Serie C1) Coppa Italia Serie CFase a gironi Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Mastropasqua (32) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Rambaudi (12) StadioComunale 1985-1986 1987-1988 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti l'Associazione Calcio Pavia nelle competizio...

Bagian dari seri tentangHierarki Gereja KatolikSanto Petrus Gelar Gerejawi (Jenjang Kehormatan) Paus Kardinal Kardinal Kerabat Kardinal pelindung Kardinal mahkota Kardinal vikaris Moderator kuria Kapelan Sri Paus Utusan Sri Paus Kepala Rumah Tangga Kepausan Nunsio Apostolik Delegatus Apostolik Sindik Apostolik Visitor apostolik Vikaris Apostolik Eksarkus Apostolik Prefek Apostolik Asisten Takhta Kepausan Eparkus Metropolitan Batrik Uskup Uskup agung Uskup emeritus Uskup diosesan Uskup agung u...

Russian interest in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings awoke soon after its publication in 1955, long before the first Russian translation. The first effort at publication was made in the 1960s, but in order to comply with literary censorship in Soviet Russia, the work was considerably abridged and transformed. The ideological danger of the book was seen in the hidden allegory 'of the conflict between the individualist West and the totalitarian, Communist East',[1] while Marxis...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (mars 2009). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? Com...

Questa voce sugli argomenti Unione europea e diritto internazionale è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. La Scuola europea di amministrazione (European Administrative School, EAS) è un organismo interistituzionale dell'Unione europea fondato il 26 gennaio 2005 per fornire una preparazione specializzata al personale amministrativo di tutte le Istituzioni comunitarie. La Scuola è divisa in d...

RandstadRail station in Zoetermeer This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: De Leyens RandstadRail station – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) De LeyensGeneral informationLocationNetherlandsCoordinates52°04′18″N 4°29′43″E / 52.0...

American sportswriter (1905–1982) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Red Smith sportswriter – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Red SmithRed SmithBornWalter Wellesley Smith(1905-09-25)September 25, 1905Green Bay, Wisconsin...

Als Jahreszeitenklima wird das Klima derjenigen Klimazonen bezeichnet, in denen sich im Jahresverlauf deutlich warme und kalte Jahreszeiten voneinander unterscheiden lassen. Die Schwankungen der mittleren Monatstemperaturen innerhalb eines Jahres sind höher als die Schwankung zwischen dem Tageshöchstwert und dem nächtlichen Tiefstwert eines Tages. Die Jahreszeiten entstehen dadurch, dass der Einstrahlungswinkel der Sonnenstrahlen im Laufe des Jahres variiert. Die Klimazonen, die von Jahres...

Menotomy redirects here. For figure of speech, see Metonymy. Town in Massachusetts, United StatesArlington, MassachusettsTownArlington Town Hall FlagCoat of armsMotto(s): Libertatis Propugnatio Hereditas Avita (Latin)The Defense of Liberty Is Our Ancestral HeritageLocation in MassachusettsArlingtonShow map of MassachusettsArlingtonShow map of the United StatesArlingtonShow map of North AmericaCoordinates: 42°24′55″N 71°09′25″W / 42.41528°N 71.15694°W /...

Tanto di cappello a JeevesTitolo originaleJeeves and the Feudal Spirit Altri titoliBertie Wooster Sees It Through; Jeeves e la cavalleria AutoreP. G. Wodehouse 1ª ed. originale1954 1ª ed. italiana1955 Genereromanzo Sottogenereumoristico Lingua originaleinglese AmbientazioneBrinkley Court SerieJeeves Preceduto daChiamate Jeeves Seguito daJeeves taglia la corda Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Tanto di cappello a Jeeves (Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit) è un romanzo umoristico del...

Dalam nama Tionghoa ini, nama keluarganya adalah Kuo. Kuo Hsing-chunInformasi pribadiTim nasionalTaiwanLahir26 November 1993 (umur 30)Yilan, TaiwanTahun aktif2011–Tinggi155 m (508 ft 6 in)Berat5.855 kg (12.908 pon) OlahragaNegaraTaiwanOlahragaAngkat besiLomba58 kg (2011–2018), 59 kg (2018–)KlubUniversitas Katolik Fu JenPrestasi dan gelarPeringkat pribadi terbaikSnatch: 110 kg (2021)Clean and jerk: 142 kg (2017)Total: 249 kg (20...

Joni MitchellJoni Mitchell nel 2013 Nazionalità Canada GenereFolk[1]Folk pop[2]Jazz[3] Periodo di attività musicale1963 – 20022006 – 20072022 – in attività StrumentoVoce, chitarra, pianoforte, dulcimer EtichettaReprise, Asylum Records, Geffen Records, Nonesuch Records, Hear Music Album pubblicati27 Studio19 Live2 Raccolte6 Sito ufficiale Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Joni Mitchell, nome d'arte di Roberta ...