1913 El Paso smelters' strike

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Baringin RayaKelurahanKantor Kelurahan Baringin RayaNegara IndonesiaProvinsiSumatera UtaraKabupatenSimalungunKecamatanRayaKodepos21162Kode Kemendagri12.08.29.1018 Kode BPS1209100020 Luas... km²Jumlah penduduk... jiwaKepadatan... jiwa/km² Baringin Raya merupakan salah satu kelurahan yang ada di kecamatan Raya, kabupaten Simalungun, provinsi Sumatera Utara, Indonesia. Pemerintahan Kelurahan Baringin Raya terdiri dari Lingkungan Baringin Raya, Buluristangan, Huta Rih, Juma Sihala, Mariah ...

AnjunDesaNegara IndonesiaProvinsiJawa BaratKabupatenPurwakartaKecamatanPleredKode pos41162Kode Kemendagri32.14.04.2009 Luas... km²Jumlah penduduk3.430 jiwaKepadatan... jiwa/km² Anjun adalah desa di kecamatan Plered, Purwakarta, Jawa Barat, Indonesia. Desa ini merupakan desa yang ber administrasi khusus seperti daerah kebanyakan di desa lainnya yang berada di sekitar Desa Anjun Pariwisata Pariwisata di desa anjun bisa dikatakan benar benar berkembang sangat pesat. Gunung Cupu Panorama G...

Junqali جونقليJongleiNegara bagian BenderaLokasi di Sudan Selatan.Negara Sudan SelatanRegionNil Hulu RayaJumlah konti12Ibu kotaBorPemerintahan • GubernurKuol Manyang Juuk (SPLM)Luas • Total122.479 km2 (47,289 sq mi)Populasi (2008) • Total1.358.602Zona waktuUTC+3 (EAT) Junqali (bahasa Arab: جونقلي) adalah sebuah negara bagian di Sudan Selatan yang memiliki luas wilayah 122.479 km² dan populasi 1.358.602 jiwa (2008)....

Эта статья описывает ситуацию применительно лишь к одному региону, возможно, нарушая при этом правило о взвешенности изложения. Вы можете помочь Википедии, добавив информацию для других стран и регионов. Встреча на 85-й годовщине Питтсбургской ассоциации глухих Протесту...

Events at the2001 World ChampionshipsTrack events100 mmenwomen200 mmenwomen400 mmenwomen800 mmenwomen1500 mmenwomen5000 mmenwomen10,000 mmenwomen100 m hurdleswomen110 m hurdlesmen400 m hurdlesmenwomen3000 msteeplechasemen4 × 100 m relaymenwomen4 × 400 m relaymenwomenRoad eventsMarathonmenwomen20 km walkmenwomen50 km walkmenField eventsHigh jumpmenwomenPole vaultmenwomenLong jumpmenwomenTriple jumpmenwomenShot putmenwomenDiscus throwmenwomenHammer throwmenwomenJavelin throwmenwomenCombined ...

Box Office MojoURLboxofficemojo.comTipeFilmPerdagangan ?YaRegistrationTidak diwajibkanLangueInggrisBagian dariAmazon PemilikAmazon.comPembuatBrandon GrayService entry1997NegaraAmerika Serikat Peringkat Alexa 1,760 (Menurut pada 6 Agustus 2019) [1]KeadaanAktif Box Office Mojo adalah situs web yang melacak pendapatan box office secara sistematis, algoritmik. Situs ini didirikan pada 1999, dan dibeli pada 2008 oleh IMDb, yang sendiri dimiliki oleh Amazon. Dari tahun 2002 hingga 2011...

Bryan AdamsInformasi latar belakangNama lahirBryan Guy AdamsLahir5 November 1959 (umur 64)AsalKingston, Ontario, KanadaGenreArena RockSoft rockHard RockAlbum Oriented RockPop RockPekerjaanPenyanyi, penulis lagu, gitaris, fotograferInstrumenVokal, Gitar, Gitar bass, Piano, HarmonikaTahun aktif1977 – SekarangLabelA&M, Badman/Polydor, Universal MusicSitus webBryanAdams.com Bryan Guy Adams OC, OBC, (lahir 5 November 1959) adalah seorang penyanyi rock Kanada, gitaris, penulis lagu dan f...

Chris Brunt Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Christopher BruntTanggal lahir 14 Desember 1984 (umur 39)Tempat lahir Belfast, Irlandia UtaraTinggi 1,85 m (6 ft 1 in)[1]Posisi bermain Gelandang SayapInformasi klubKlub saat ini West Bromwich AlbionNomor 11Karier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2002–2004 Middlesbrough 0 (0)2004 → Sheffield Wednesday (pinjaman) 6 (2)2004–2007 Sheffield Wednesday 137 (22)2007– West Bromwich Albion 168 (31)Tim nasional‡2002–2003 Irl...

Apache leader For other uses, see Victorio (disambiguation). VictorioBidu-ya, BeduiatPossibly VictorioTchihende Apache leaderPreceded byCuchillo Negro (Warm Springs Tchihende), Mangas Coloradas (Coppermine Tchihende)Succeeded byNana Personal detailsBornc. 1825Chihuahua, First Mexican RepublicDied(1880-10-14)October 14, 1880 (aged 55)Tres Castillos, Chihuahua, MexicoCause of deathKilled by Mexican soldiers during the Battle of Tres CastillosResting placeDoña Ana County, New Mexico, ...

2013 American filmThe Disappearance of Eleanor RigbyTheatrical release posterDirected byNed BensonWritten byNed BensonProduced by Cassandra Kulukundis Ned Benson Jessica Chastain Todd J. Labarowski Emanuel Michael Starring Jessica Chastain James McAvoy Nina Arianda Viola Davis Bill Hader Ciarán Hinds Isabelle Huppert William Hurt Jess Weixler CinematographyChristopher BlauveltEdited byKristina BodenMusic byRyan Lott (under the alias Son Lux)Productioncompanies Division Films Dreambridge Film...

Aspect of Hindu goddess Lakshmi Miniature, c. 1780 Gajalakshmi (Sanskrit: गजलक्ष्मी, romanized: Gajalakṣmī, lit. 'Elephant Lakshmi'), also spelt as Gajalaxmi, is one of the most significant Ashtalakshmi aspects of the Hindu goddess of prosperity, Lakshmi.[1] Mythology In Hindu mythology, Gajalakshmi is regarded to have restored the wealth and power lost by Indra when she rose from the Samudra Manthana, the churning of the ocean.[2] She i...

American businessman and politician (born 1954) For other people with similar names, see Michael Braun (disambiguation). Mike BraunOfficial portrait, 2019United States Senatorfrom IndianaIncumbentAssumed office January 3, 2019Serving with Todd YoungPreceded byJoe DonnellyRanking Member of the Senate Aging CommitteeIncumbentAssumed office January 3, 2023Preceded byTim ScottMember of the Indiana House of Representativesfrom the 63rd districtIn officeNovember 5, 2014&...

Japanese-born American theoretical physicist (1925–2023) Toichiro KinoshitaBorn木下東一郎, Kinoshita Tōichirō(1925-01-23)January 23, 1925DiedMarch 23, 2023(2023-03-23) (aged 98)OccupationTheoretical physicistKnown forKinoshita–Lee–Nauenberg theoremCornell potentialAwardsSakurai prize (1990)Guggenheim Fellowship (1973)Academic backgroundEducationUniversity of TokyoDoctoral advisorSin-Itiro TomonagaAcademic workDisciplinePhysicsSub-disciplineTheoretical PhysicsInstitution...

Southern part of Manhattan, New York City Central business district in New York, United StatesLower Manhattan Downtown Manhattan, Downtown New York CityCentral business districtLower Manhattan, including Wall Street, anchoring New York City's role as the world's principal fintech and financial center,[1] with One World Trade Center, the tallest skyscraper in the Western HemisphereCountry United StatesState New YorkCityNew York CityBoroughManhattanSettled1626Population (...

مقاطعة كامدين الإحداثيات 38°02′N 92°46′W / 38.03°N 92.77°W / 38.03; -92.77 [1] تاريخ التأسيس 29 يناير 1841 تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2] التقسيم الأعلى ميزوري العاصمة كامدنتون التقسيمات الإدارية كامدنتون خصائص جغرافية المساحة 1836...

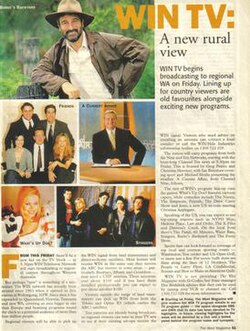

Australian TV network This article is about the Australian television network. For the network's flagship station, see WIN (TV station). For other television networks called WIN, see WIN TV. Television channel WIN TelevisionCountryAustraliaBroadcast areaRegional Queensland, Northern NSW & Gold Coast, Southern NSW & ACT, Griffith, Regional Victoria, Mildura, Tasmania, Eastern SA, Regional WAAffiliatesNine NetworkSeven Network (Griffith and Eastern SA)Network 10 (Gold Coast, Northern NS...

American politician George Zalmon ErwinBorn(1840-01-15)January 15, 1840Madrid, New YorkDiedJanuary 16, 1894(1894-01-16) (aged 54)Potsdam, New YorkEducationMiddlebury College (1865) George Zalmon Erwin (January 15, 1840 – January 16, 1894) was an American politician. Life He was born on January 15, 1840, in Madrid, St. Lawrence County, New York. He was educated at Saint Lawrence Academy at Potsdam, New York. He graduated from Middlebury College in August, 1865. He studied law with the t...

Getting AcquaintedArah jarum jam dari atas: Phyllis Allen, Mack Swain, Charles Chaplin dan Mabel NormandSutradaraCharles ChaplinProduserMack SennettDitulis olehCharles ChaplinPemeranCharles ChaplinMabel NormandPhyllis AllenMack SwainHarry McCoyEdgar KennedyCecile ArnoldSinematograferFrank D. WilliamsPerusahaanproduksiKeystone StudiosDistributorMutual FilmTanggal rilis 05 Desember 1914 (1914-12-05) Durasi16 menitNegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaFilm bisuInggris (titel asli) Film lengkap Getting...

2022 terrorist attack in Israel 2022 Beersheba attackclass=notpageimage| The attack siteLocationBeersheba, IsraelCoordinates31°14′43″N 34°48′41″E / 31.24528°N 34.81139°E / 31.24528; 34.81139DateMarch 22, 2022; 2 years ago (2022-03-22) 16:10 – 16:18Attack typeVehicle-ramming attack, mass stabbingDeaths4 civilians (+1 assailant)Injured2 civiliansAssailantMohammed Abu al-KiyanDefenderArthur Chaimov On March 22, 2022, four people were k...

Yahudi Rusia היהודים הרוסיים / יהדות רוסיה Русские евреиAnton RubinsteinAbraham GoldfadenSholem AleichemLina SternMarc ChagallFaina RanevskayaGolda MeirAyn RandLev LandauMikhail BotvinnikArkady RaikinArkady RaikinMaya PlisetskayaJoseph BrodskyGrigori PerelmanSergey BrinDaerah dengan populasi signifikan Israel900,000[1] AS350,000[2] RusiaPerkiraan berbeda yang diberikan: 157,763-194,000 populasi Yahudi murni yang mengidentifika...