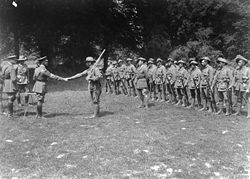

10th Brigade (Australia)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Kepah adalah sejenis kerang (bivalvia) yang termasuk hewan bertubuh lunak (moluska).Kata ini sering diterapkan hanya pada hewan yang dapat dimakan[1] dan hidup sebagai infauna, menghabiskan sebagian besar hidupnya setengah terkubur di pasir dasar laut atau dasar sungai. Kerang memiliki dua cangkang berukuran sama yang dihubungkan oleh dua otot adduktor dan memiliki kaki penggali yang kuat. Mereka hidup di lingkungan air tawar dan laut; di air asin mereka lebih suka menggali ke dalam l...

Seri Dragon BallGambar sampul Selamat Tinggal Para Pahlawan.MangaAlbum nomor35EpisodeCell SagaDidahului olehKsatria yang Melebihi GokuDiikuti denganLahirnya Pahlawan BaruDiterbitkan di Jepang1984Diterbitkan di Indonesia1994 Selamat Tinggal Para Pahlawan adalah jilid ke-35 manga Dragon Ball. Dikisahkan bahwa Cell sang makhluk iblis super kuat ciptaan Dr. Gero bisa dikalahkan, tetapi Goku tewas. lbsSeri Dragon BallDiterbitkan oleh Elex Media KomputindoGoku dan Kawan-Kawannya • Kemelut Dragon ...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (نوفمبر 2019) هذه المقالة تحتاج للمزيد من الوصلات للمقالات الأخرى للمساعدة في ترابط مقالات الموسوعة. فضلًا ساعد في تحس...

Pantai Grajagan (G-Beach), yang merupakan salah satu tempat berselancar terkenal di Semenanjung Blambangan Semenanjung Blambangan (Bhs. Osing: Blambyangan) adalah sebuah semenanjung yang terletak di ujung paling timur Pulau Jawa. Semenanjung ini berada di wilayah Kabupaten Banyuwangi, Jawa Timur. Di sebelah utara berhadapan dengan Selat Bali dan di sebelah selatan dengan Samudra Hindia. Nama Blambangan sendiri diambil dari nama kuno daerah Banyuwangi yaitu Kerajaan Blambangan, yang pada masa ...

City in Colorado, United States City in Colorado, United StatesColorado SpringsCityColorado Springs skyline with the Front Range in the background FlagLogoNicknames: Olympic City USA,[2]The Springs[3][4]Location of the City of Colorado Springs in El Paso County, ColoradoColorado SpringsLocation of the City of Colorado Springs in the United StatesShow map of ColoradoColorado SpringsColorado Springs (the United States)Show map of the United StatesColorado SpringsCol...

Aksi Ende Gelände 2019 yang menutup jalur kereta utara-selatan pembangkit listrik Neurath pada 23 Juni 2019. Ende Gelände 2019 adalah aksi besar-besaran berupa tuntutan keadilan iklim yang terjadi di pertambangan batu lignit Rhenish yang terletak di pegunungan lignit di Kölner Bucht, wilayah jarang penduduk di bagian barat daya Nordrhein-Westfalen, Jerman. Aksi damai ini menuntut untuk tidak memakai lagi bahan bakar fosil yang dipakai oleh perusahaan pembangkit listrik RWE berupa batu bara...

Ian ChenIan Chen tahun 2022Lahir07 September 2006 (umur 17)Los Angeles, California, Amerika SerikatPekerjaanAktorTahun aktif2013—sekarang Ian Chen Hanzi tradisional: 陳琦燁 Hanzi sederhana: 陈琦烨 Alih aksara Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin: Chén Qíyè Min Nan - Romanisasi POJ: Tân Kî-iap Ian Chen (lahir 7 September 2006) adalah aktor asal Amerika Serikat. Dia di kenal karena berperan sebagai Evan Huang pada serial serial komedi ABC, Fresh Off the Boat (2015-2020) dan film Shaz...

English journalist and television presenter Jennie BondBond (left) in 2012BornJennifer Bond (1950-08-19) 19 August 1950 (age 73)Hitchin, Hertfordshire, EnglandOccupation(s)Journalist, presenterNotable credit(s)BBC News royal correspondent (1989–2003)The Great British MenuCash in the AtticSpouse James Keltz (m. 1982)Children1 Jennifer Bond (born 19 August 1950) is an English journalist and television presenter. Bond worked for fourteen years as the BBC's r...

21st-century American comedy TV series ShrillGenreComedyBased onShrill: Notes from a Loud Womanby Lindy WestDeveloped by Aidy Bryant Alexandra Rushfield Lindy West Starring Aidy Bryant Lolly Adefope Luka Jones John Cameron Mitchell Ian Owens Patti Harrison Country of originUnited StatesOriginal languageEnglishNo. of seasons3No. of episodes22ProductionExecutive producers Lorne Michaels Andrew Singer Aidy Bryant Elizabeth Banks Max Handelman Lindy West Ali Rushfield ProducerDannah ShinderRunnin...

County in South Dakota, United States Not to be confused with Mellette, South Dakota. County in South DakotaMellette CountyCountyWhite River from the West, the county seatLocation within the U.S. state of South DakotaSouth Dakota's location within the U.S.Coordinates: 43°35′N 100°46′W / 43.58°N 100.76°W / 43.58; -100.76Country United StatesState South DakotaFounded1909 (created)1911 (organized)Named forArthur C. MelletteSeatWhite RiverLargest cityWhit...

Ernest Renan. Maison natale d'Ernest Renan à Tréguier. Aujourd'hui musée consacré à sa vie et son œuvre. Monument élevé en 1903 sur la place principale de Tréguier en l'honneur d'Ernest Renan représenté aux côtés d'Athéna. Plaque du monument. Joseph Ernest Renan, 28 Februari 1823 – 2 Oktober 1892 adalah seorang sastrawan, filolog, filsuf dan sejarawan Prancis. Renan sangat mengagumi ilmu. Dia langsung menerima teori Darwin mengenai evolusi spesies. Dia melihat hu...

Extinct genus of dinosaur ChilesaurusTemporal range: Late Jurassic~145 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ Cast of the holotype skeleton Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Clade: Dinosauria Genus: †ChilesaurusNovas et al. 2015 Species: †C. diegosuarezi Binomial name †Chilesaurus diegosuareziNovas et al. 2015 Chilesaurus is an extinct genus of herbivorous dinosaur. The type and only known species so far is Chilesaurus d...

Ця стаття потребує додаткових посилань на джерела для поліпшення її перевірності. Будь ласка, допоможіть удосконалити цю статтю, додавши посилання на надійні (авторитетні) джерела. Зверніться на сторінку обговорення за поясненнями та допоможіть виправити недоліки. Мат...

Species of tree native to North America Sequoiadendron giganteum The Grizzly Giant in the Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park Conservation status Endangered (IUCN 3.1)[1] Vulnerable (NatureServe)[2] Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae Clade: Tracheophytes Clade: Gymnospermae Division: Pinophyta Class: Pinopsida Order: Cupressales Family: Cupressaceae Genus: Sequoiadendron Species: S. giganteum Binomial name Sequoiadendron giganteum(Lindl.) J.Buchh., ...

Volkswagen Polo Mk4InformasiProdusenVolkswagenJuga disebutVolkswagen Polo VivoMasa produksi2002–2009 (Jerman)2010–sekarang (Afrika Selatan)PerakitanWolfsburg, JermanNavarra, SpanyolBratislava, Slowakia[1]Curitiba, BrasilUitenhage, South AfricaLuanda, Angola (Ancar)Anting, China (SVW)Bodi & rangkaKelasSuperminiBentuk kerangka3-door hatchback5-door hatchback4-door sedanTata letakMesin depan, penggerak roda depanPlatformVolkswagen Group A04 (PQ24)Mobil terkaitSEAT Ibiza...

Meditative repetition of a mantra For other uses, see Japa (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Japan. A Bhutanese Buddhist woman doing Japa, with prayer beads. Japa (Sanskrit: जप) is the meditative repetition of a mantra or a divine name. It is a practice found in Hinduism,[1] Jainism,[2] Sikhism,[3][4] and Buddhism,[5] with parallels found in other religions. Japa may be performed while sitting in a meditation posture, while performing other ...

Professional ice hockey exhibition game 2020 NHL All–Star GameEnterprise Center, St. LouisJanuary 25, 2020Game oneAtlantic 9 – Metropolitan 5Game twoPacific 10 – Central 5Game threePacific 5 – Atlantic 4MVPDavid Pastrnak ← 2019 2022 → The 2020 National Hockey League All-Star Game was held on January 25, 2020, at the Enterprise Center in St. Louis, Missouri, the home of the St. Louis Blues.[1] The city previously hosted the NHL All-Star Game in 1970 and 19...

River in New Hampshire, United StatesBellamy RiverBellamy River Dam c. 1910Show map of New HampshireShow map of the United StatesLocationCountryUnited StatesStateNew HampshireCountyStraffordMunicipalitiesBarrington, Madbury, DoverPhysical characteristicsSourceSwains Lake • locationBarrington • coordinates43°11′14″N 71°1′28″W / 43.18722°N 71.02444°W / 43.18722; -71.02444 • elevation279 ft (85 m) ...

تقسيم الفلسفة إلى فلسفة نظرية (بالإنجليزية: Theoretical philosophy) وفلسفة عملية يرجع إلى تقسيمات أرسطو للفلسفة الأخلاقية والطبيعية. فالأولى تهتم بقواعد السلوك النظرية، بينما الثانية فهي التطبيق العملي لذلك.[1][2] خلفية في الدنمارك، وفنلندا، وبولندا، والسويد، يتم تدريس دو�...

Questa voce sull'argomento contee dell'Indiana è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Contea di RipleyconteaLocalizzazioneStato Stati Uniti Stato federato Indiana AmministrazioneCapoluogoVersailles Data di istituzione1816 TerritorioCoordinatedel capoluogo39°06′00″N 85°15′36″W39°06′00″N, 85°15′36″W (Contea di Ripley) Superficie1 160 km² Abitanti26 523 (2000) Densità22,86 ab./km² Altre informazio...