The Fight (book)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Foto konjungsi agung pada tahun 2020 diambil dua hari sebelum konjungsi terdekat antara Jupiter (kanan bawah) dan Saturnus (kiri atas) yang dipisahkan oleh sekitar 15 menit busur. Empat satelit Galileo terlihat di sekitar Jupiter: pada sekitar posisi jam 10 di kiri atas Yupiter adalah Kalisto, Ganimede, dan Europa; muncul lebih dekat ke Jupiter di kanan bawahnya adalah Io. Konjungsi agung atau kesegarisan agung adalah konjungsi planet Jupiter dan Saturnus, ketika dua planet mendekat pada titi...

Approach to ethics Part of a series onFeminist philosophy Major works A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) The Subjection of Women (1869) The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884) The Second Sex (1949) The Feminine Mystique (1963) Sexual Politics (1969) The Dialectic of Sex (1970) Speculum of the Other Woman (1974) This Sex Which is Not One (1977) Gyn/Ecology (1978) Throwing Like a Girl (1980) In a Different Voice (1982) The Politics of Reality (1983) Wo...

Untuk pemberhentian Lin Bogor, lihat Stasiun Jayakarta. Kereta api JayakartaKereta api Jayakarta mengarah Surabaya (via Yogyakarta) meninggalkan Stasiun TambunInformasi umumJenis layananKereta api antarkotaStatusBeroperasiDaerah operasiDaerah Operasi I JakartaPendahuluGBMS PremiumMulai beroperasi 15 Juni 2017 (sebagai GBMS Premium) 28 September 2017; 6 tahun lalu (2017-09-28) (sebagai Jayakarta) Operator saat iniKereta Api Indonesia (KAI)Lintas pelayananStasiun awalPasar SenenJumlah pemb...

Sitiveni Ligamanda Rabuka Perdana Menteri Fiji ke-3PetahanaMulai menjabat 24 Desember 2022PendahuluFrank BainimaramaPenggantiPetahanaMasa jabatan2 Juni 1992 – 19 Mei 1999PendahuluRatu Sir Kamisese MaraPenggantiMahendra ChaudhryKetua Dewan Agung penasihat militerMasa jabatan1999 – 3 Mei 2001PenggantiRatu Epeli Ganilau Informasi pribadiLahir13 September 1948 (umur 75)Nakobo, on Vanua Levu IslandPartai politikPeople's AllianceSuami/istriSuluweti Camaivuna Tuiloma (...

Film by Alfred Hitchcock This article is about the 1960 film. For the 1998 remake, see Psycho (1998 film). For the sequels, see Psycho (franchise). PsychoTheatrical release posterby Macario Gómez Quibus[1]Directed byAlfred HitchcockScreenplay byJoseph StefanoBased onPsychoby Robert BlochProduced byAlfred HitchcockStarring Anthony Perkins Vera Miles John Gavin Martin Balsam John McIntire Janet Leigh CinematographyJohn L. RussellEdited byGeorge TomasiniMusic byBernard HerrmannProductio...

Mexican journalist and photographer and murder victim In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Espinosa and the second or maternal family name is Becerril. Rubén EspinosaBornRubén Manuel Espinosa BecerrilNovember 29, 1983Mexico City, MexicoDiedJuly 31, 2015 (aged 31)Mexico City, MexicoCause of deathMurder from gunfireResting placePanteón De Dolores, MexicoNationalityMexicanOccupationPhotojournalistEmployer(s)AVC News agency, Proceso and Cuartoscuro magazinesKnown...

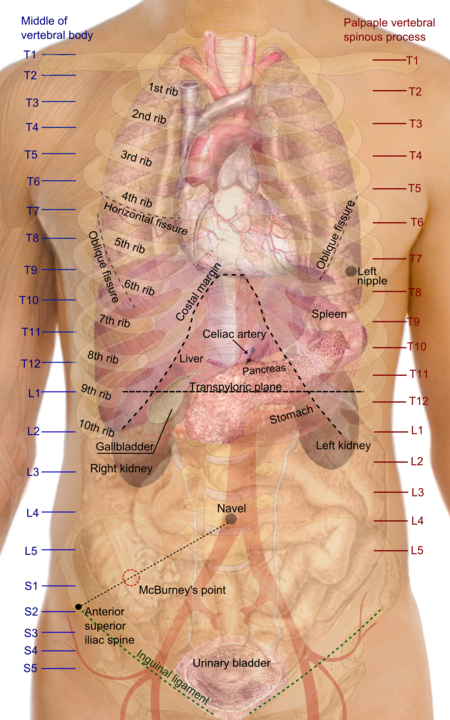

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Hati (disambiguasi). artikel mengandung terlalu banyak istilah teknis. Tolong bantu mengembangkannya agar dapat dipahami oleh orang awam, tanpa harus menghilangkan aspek teknisnya. (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) HatiHati manusiaGambar organ dalam manusia, hati (bahasa Inggris: liver) terletak di tengah.RincianSarafceliac ganglia, vagus[1]PengidentifikasiBahasa Latinjecur, iecerMeSHD008099TA98A05.8.01.001TA23023FMA7197...

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: Live at the Sugar Club – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2015) The topic of thi...

Article 48 de la Charte des droits fondamentaux de l'Union européenne traitant de la présomption d'innocence (en anglais). La présomption d'innocence est un principe juridique selon lequel toute personne qui se voit reprocher une infraction est réputée innocente tant que sa culpabilité n’a pas été légalement démontrée. La plupart des pays d'Europe reconnaissent et utilisent le principe de la présomption d'innocence (article 6 de la Convention européenne des droits de l'homme)[1...

RanisCittà, apparten. a una Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Ranis – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Germania Land Turingia DistrettoNon presente CircondarioSaale-Orla AmministrazioneSindacoAndreas Gliesing TerritorioCoordinate50°39′50″N 11°34′05″E / 50.663889°N 11.568056°E50.663889; 11.568056 (Ranis)Coordinate: 50°39′50″N 11°34′05″E / 50.663889°N 11.568056°E50.663889; 11.568056 (Ranis) Altitudine380 m s.l.m. Superficie10,5...

此条目页介紹的是中华人民共和国国务院民用航空行政主管部门。 關於1952-1987年以“政企合一”模式经营民用航空事业之运营历史,請見「中国民航 (运营时期)」。 關於与“中国民航局”相近的其他义项,請見「中國民航局 (消歧义)」。 中国民用航空局 1999年规定:印章直径4.5厘米,中央刊国徽,由国务院制发。 中国民用航空局局徽 主要领导 局长 宋志勇 副局�...

North American collegiate sorority Kappa Beta GammaΚΒΓFoundedJanuary 22, 1917; 107 years ago (January 22, 1917)Marquette University in Milwaukee, WITypeSocialAffiliationIndependentScopeInternationalMottoCharacter, Culture, CourageColors Deep Sapphire, Pearl White and Old GoldSymbolFive-pointed StarFlowerForget-me-notJewelBlue Sapphire and White PearlMascotJermain the LionPublicationKappa StarPhilanthropySpecial OlympicsChapters32 active, 24 inactiveColonies...

نظام ويندوز الفرعي للينكسمعلومات عامةنوع مكون في نظام تشغيل مايكروسوفت ويندوز النظام الفرعي البيئي نظام التشغيل ويندوز 10ويندوز 11 النموذج المصدري حقوق التأليف والنشر محفوظة المطورون مايكروسوفت المدونة الرسمية devblogs.microsoft.com… (الإنجليزية) موقع الويب learn.microsoft.com… (الإنجليز�...

العلاقات البولندية الكوبية بولندا كوبا بولندا كوبا تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات البولندية الكوبية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين بولندا وكوبا.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: وجه المقارنة بولندا كوب...

此條目没有列出任何参考或来源。 (2018年9月17日)維基百科所有的內容都應該可供查證。请协助補充可靠来源以改善这篇条目。无法查证的內容可能會因為異議提出而被移除。 此條目需要精通或熟悉相关主题的编者参与及协助编辑。 (2018年3月17日)請邀請適合的人士改善本条目。更多的細節與詳情請參见討論頁。 Yunnan Lvshan Landscape車隊資訊UCI代碼YUN注册地中国成立年份2014項目�...

Color shade of bright red Scarlet Color coordinatesHex triplet#FF2400sRGBB (r, g, b)(255, 36, 0)HSV (h, s, v)(8°, 100%, 100%)CIELChuv (L, C, h)(55, 172, 14°)SourceX11ISCC–NBS descriptorVivid reddish orangeB: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) Scarlet is a bright red color,[1][2] sometimes with a slightly orange tinge.[3] In the spectrum of visible light, and on the traditional color wheel, it is one-quarter of the way between red and orange, sli...

American politician (1837–1899) Benjamin H. CloverMember of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom Kansas's 3rd districtIn officeMarch 4, 1891 – March 3, 1893Preceded byBishop W. PerkinsSucceeded byThomas Jefferson Hudson Personal detailsBorn(1837-12-22)December 22, 1837Jefferson, OhioDiedDecember 30, 1899(1899-12-30) (aged 62)Douglass, KansasPolitical partyPopulist Benjamin Hutchinson Clover (December 22, 1837 – December 30, 1899) was a U.S. Representative from...

Spanish marshal and statesman In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Serrano and the second or maternal family name is Domínguez. The Most ExcellentFrancisco SerranoDuke of la TorrePortrait by NadarPresident of SpainIn office3 January 1874 – 31 December 1874Prime MinisterHimselfJuan de ZavalaPráxedes Mateo SagastaPreceded byEmilio CastelarSucceeded byAlfonso XII(as King of Spain)Prime Minister of SpainIn office3 January 1874 – 26 February 1874Pr...

Camp de RivesaltesLe camp de Rivesaltes en 2007.PrésentationType Camp de prisonniers de guerre, camp d'internement françaisSurface 6 000 000 m2Propriétaire ÉtatPatrimonialité Patrimoine du XXe s. Inscrit MH (2000)LocalisationDépartement Pyrénées-OrientalesCommune Rivesaltes et Salses-le-ChâteauCoordonnées 42° 48′ 29″ N, 2° 53′ 24″ ELocalisation sur la carte des Pyrénées-OrientalesLocalisation sur la carte de Francemodifier - m...

1983 codification of canonical legislation for the Latin Catholic Church Cover of the 1983 edition of the 1983 Code of Canon Law Part of a series on theCanon law of theCatholic Church Ius vigens (current law) 1983 Code of Canon Law Omnium in mentem Magnum principium Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches Ad tuendam fidem Ex corde Ecclesiae Indulgentiarum Doctrina Praedicate evangelium Veritatis gaudium Custom Matrimonial nullity trial reforms of Pope Francis Documents of the Second Vatican Co...