Sunni view of Ali

|

Read other articles:

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع نورث هيفن (توضيح). نورث هيفن الإحداثيات 41°01′13″N 72°18′44″W / 41.0203°N 72.3122°W / 41.0203; -72.3122 [1] تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة سوفولك خصائص جغرافية المساحة 7.025758 كيلومتر مربع7.025967 كيلومتر مر�...

Football team representing Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabia Under-23 and Olympic TeamNickname(s)الصقور الخضر(The Green Falcons)AssociationAFC (Asia)Head coachSaad Al-ShehriHome stadiumKing Fahd International StadiumFIFA codeKSA First colours Second colours Olympic GamesAppearances3 (first in 1984)Best resultFirst Round (1984, 1996, 2020)AFC U-23 Asian CupAppearances5 (first in 2013)Best result Champions (2022)Asian GamesAppearances2 (first in 2014)Best resultQuarter-finals (2014, 2018, 20...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Rewind Paolo Nutini song – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) 2006 single by Paolo NutiniRewindSingle by Paolo Nutinifrom the album These Streets Released4 December 2006Recorded...

Questa voce sull'argomento calciatori brasiliani è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Edílson Mendes Guimarães Nazionalità Brasile Altezza 177 cm Peso 78 kg Calcio Ruolo Difensore Squadra svincolato Carriera Giovanili 2002-2005 Avaí Squadre di club1 2005 Avaí? (?)2005 Vitória? (?)2006 Atlético Mineiro? (?)2006-2008 Avaí? (?)2008 Veranópolis? (?)20...

British politician The Right HonourableThe Lord CockfieldPC1952 portraitEuropean Commissioner for Internal Market and ServicesIn office7 January 1985 – 5 January 1989PresidentJacques DelorsPreceded byKarl-Heinz NarjesSucceeded byMartin BangemannChancellor of the Duchy of LancasterIn office11 June 1983 – 11 September 1984MonarchElizabeth IIPrime MinisterMargaret ThatcherPreceded byCecil ParkinsonSucceeded byThe Earl of GowrieSecretary of State for TradePresident of the Bo...

CelimpunganNama lain...Jenis...Sajian...Tempat asalIndonesiaDaerahSumatera SelatanBahan utamaDaging ikan, Sagu, SantanSunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Celimpungan adalah makanan yang berasal dari Sumatera Selatan. Bahan dasar celimpungan adalah adonan sagu dan ikan seperti halnya Pempek yang juga berasal dari Sumatera Selatan. Perbedaan di antara keduanya terletak pada bentuk dan kuahnya. Celimpungan berbentuk bulat dengan diameter 10 cm dan tipis (p...

Rural district in West Azerbaijan province, Iran For the village, see Tala Tappeh. Rural District in West Azerbaijan, IranTala Tappeh Rural District دهستان طلاتپهRural DistrictTala Tappeh Rural DistrictCoordinates: 37°44′18″N 45°12′39″E / 37.73833°N 45.21083°E / 37.73833; 45.21083[1]CountryIranProvinceWest AzerbaijanCountyUrmiaDistrictNazluCapitalTala TappehPopulation (2016)[2] • Total2,278Time zoneUTC+...

Jan MatejkoLahirJan Mateyko24 Juni 1838Kota Merdeka KrakówMeninggal1 November 1893(1893-11-01) (umur 55)Kraków, Polandia AustriaMakamPemakaman RakowickiKebangsaanPolandiaPendidikanSekolah Seni Rupa KrakówAkademi Seni Rupa MünchenDikenal atasSeni lukisKarya terkenalBattle of GrunwaldStańczykThe Prussian HomageThe Hanging of the Sigismund bellGerakan politikLukisan sejarahSuami/istriTeodora Matejko Jan Alojzy Matejko (pengucapan bahasa Polandia: [jan aˈlɔjzɨ maˈtɛjko]; juga...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento calciatori italiani non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Alessandro Bonesso Bonesso al Catania nella stagione 1980-1981 Nazionalità Italia Altezza 180 cm Peso 79 kg Calcio Ruolo Attaccante Termine carriera 1989 CarrieraGiovanili 1973-1975 Saronno...

1 Samuel 28Kitab Samuel (Kitab 1 & 2 Samuel) lengkap pada Kodeks Leningrad, dibuat tahun 1008.KitabKitab 1 SamuelKategoriNevi'imBagian Alkitab KristenPerjanjian LamaUrutan dalamKitab Kristen9← pasal 27 pasal 29 → 1 Samuel 28 (atau I Samuel 28, disingkat 1Sam 28) adalah bagian dari Kitab 1 Samuel dalam Alkitab Ibrani dan Perjanjian Lama di Alkitab Kristen. Dalam Alkitab Ibrani termasuk Nabi-nabi Awal atau Nevi'im Rishonim [נביאים ראשונים] dalam bagian Nevi'im (נב...

Darryl F. Zanuck Darryl F. Zanuck en 1964. Données clés Nom de naissance Darryl Francis Zanuck Naissance 5 septembre 1902Wahoo (Nebraska) Nationalité Américaine Décès 22 décembre 1979 (à 77 ans)Palm Springs (Californie) Profession Producteur de cinémaRéalisateurScénariste Films notables Les Raisins de la colèreÈveDavid et BethsabéeLes Neiges du KilimandjaroLe Jour le plus longCléopâtre modifier Darryl Francis Zanuck est un producteur de cinéma, réalisateur et scénaris...

The following is a list of episodes for the anime series Yu-Gi-Oh! 5D's (遊戯王ファイブディーズ, Yūgiō Faibu Dīzu), which began airing in Japan on April 2, 2008. The series is currently licensed for release in North America by Konami. However, only 31 episodes from seasons 4 and 5 were dubbed into English by 4Kids Entertainment, due to low ratings, pressure to air Yu-Gi-Oh! Zexal, and an ongoing lawsuit from TV Tokyo and NAS.[1] Series overview SeasonEpisodesOriginally ...

Cycling race Men's under-23 time trial2010 UCI Road World ChampionshipsRainbow jerseyRace detailsDatesSeptember 29, 2010Stages1Distance31.6 km (19.64 mi)Winning time42' 50.29Medalists Gold Taylor Phinney (USA) (United States) Silver Luke Durbridge (AUS) (Australia) Bronze Marcel Kittel (GER) (Germany)← 2009 2011 → Events at the 2010 UCIRoad World ChampionshipsParticipating nationsElite events...

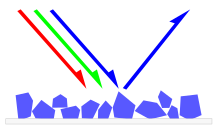

Colored material Pigments redirects here. For album, see Pigments (album). Pigments for sale at a market stall in Goa, India A pigment is a powder used to add color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly insoluble and chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored substances which are soluble or go into solution at some stage in their use.[1][2] Dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic. Pigme...

2002 AA29Discovery[1]Discovered byLINEARDiscovery dateJanuary 9, 2002DesignationsAlternative designationsnoneMinor planet categoryAten asteroidOrbital characteristics[2]Epoch 13 January 2016 (JD 2457400.5)Uncertainty parameter 0Observation arc736 days (2.02 yr)Aphelion1.0055 AU (150.42 Gm)Perihelion0.97963 AU (146.551 Gm)Semi-major axis0.99259 AU (148.489 Gm)Eccentricity0.013047Orbital period (sidereal)0.99 yr (361.2 d)Average orbit...

American actor and filmmaker (born 1969) For the basketball player, see Tylor Perry. For the rock duo, see Toxic Twins. Tyler PerryPerry being interviewed for Boo! A Madea Halloween in 2016BornEmmitt Perry Jr. (1969-09-13) September 13, 1969 (age 54)New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.OccupationsActorfilm producerdirectorwriterplaywrightentrepreneurYears active1992–presentPartnerGelila Bekele (2009–2020)Children1Websitetylerperry.com Tyler Perry (born Emmitt Perry Jr.; September 13, 19...

Pacar kuku Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Plantae (tanpa takson): Tracheophyta (tanpa takson): Angiospermae (tanpa takson): Eudikotil (tanpa takson): Rosid Ordo: Myrtales Famili: Lythraceae Genus: Lawsonia[1]L. Spesies: L. inermis Nama binomial Lawsonia inermisL. Sinonim[2] Alcanna spinosa (L.) Gaertn. Casearia multiflora Spreng. Lawsonia alba Lam. nom. illeg. Lawsonia speciosa L. Lawsonia spinosa L. Rotantha combretoides Baker Pacar Kuku (Lat: Lawsonia inermis L.) adalah ...

Wawan MattaliuS.Ksi. Anggota DPRD Provinsi Sulawesi SelatanMasa jabatan24 September 2009 – 11 Februari 2014 (mengundurkan diri)PresidenSusilo Bambang YudhoyonoGubernurSyahrul Yasin LimpoPenggantiYunus TiroDaerah pemilihanSULAWESI SELATAN IVMaros, Pangkep, Barru, ParepareMayoritas7.833 suaraMasa jabatan24 September 2014 – 24 September 2019PresidenSusilo Bambang YudhoyonoJoko WidodoGubernurSyahrul Yasin LimpoSoni Sumarsono (Pj.)Nurdin AbdullahDaerah pemilihanSULAWESI SELAT...

Television channel For the American TV channel owned by First Media, see BabyFirst. Television channel BabyTVCountryUnited KingdomIsraelUnited StatesEurope (except Russia, Latvia and Italy)Broadcast areaWorldwideHeadquartersLondon[1]ProgrammingPicture format1080i HDTV(downscaled to 576i/480i for the SD feed)OwnershipOwnerThe Walt Disney Company Limited (Disney Entertainment)Sister channels List Disney Channel Disney Jr. Disney XD ABC A&E ACC Network Lifetime LMN Localish LHN ESPN ...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Воздвиженка. Улица Воздвиженка Воздвиженка (слева особняк Арсения Морозова, на дальнем плане Кремль), 2004 год Общая информация Страна Россия Город Москва Округ ЦАО Район Арбат Протяжённость 600 м Метро Арбатская Арбатская Б�...