Statue of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Chlorophorus austerus Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Arthropoda Kelas: Insecta Ordo: Coleoptera Famili: Cerambycidae Subfamili: Cerambycinae Tribus: Clytini Genus: Chlorophorus Spesies: Chlorophorus austerus Chlorophorus austerus adalah spesies kumbang tanduk panjang yang tergolong familia Cerambycidae. Spesies ini juga merupakan bagian dari genus Chlorophorus, ordo Coleoptera, kelas Insecta, filum Arthropoda, dan kingdom Animalia. Larva kumbang ini biasanya mengebor ke dalam k...

Academy Awards ke-71Poster resmiTanggal21 Maret 1999TempatDorothy Chandler Pavilion Los Angeles, California, A.S.Pembawa acaraWhoopi GoldbergPembawa pra-acaraGeena DavisJim Moret[1]ProduserGil CatesPengarah acaraLouis J. HorvitzSorotanFilm TerbaikShakespeare in LovePenghargaan terbanyakShakespeare in Love (7)Nominasi terbanyakShakespeare in Love (13)Liputan televisiJaringanABCDurasi4 jam, 2 menit[2]Peringkat45.51 juta28.63% (rating Nielsen) ← ke-70 Academy Awards ke...

For other uses, see Garden of the Gods (disambiguation). Part of a series onAncientMesopotamian religionChaos Monster and Sun God Religions of the ancient Near East Anatolia Ancient Egypt Mesopotamia Babylonia Sumer Iranian Semitic Arabia Canaan Primordial beings Tiamat and Abzu Lahamu and Lahmu Kishar and Anshar Mummu Seven gods who decree Four primary Anu Enlil Enki Ninhursag Three sky gods Inanna/Ishtar Nanna/Sin Utu/Shamash Other major deities Adad Dumuzid Enkimdu Enmesharra Ereshkigal Ki...

Australian politician (born 1963) SenatorMehreen FaruqiFaruqi in 2015Deputy Leader of the Australian GreensIncumbentAssumed office 10 June 2022LeaderAdam BandtPreceded byNick McKim and Larissa WatersSenator for New South WalesIncumbentAssumed office 15 August 2018Preceded byLee RhiannonMember of the New South Wales Legislative CouncilIn office19 June 2013 – 14 August 2018Preceded byCate FaehrmannSucceeded byCate Faehrmann Personal detailsBorn (1963-07-08) 8 July 1963 (age&#...

American politician William Emil Hesscirca 1943Member of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom Ohio's 2nd districtIn officeMarch 4, 1929 – January 3, 1937Preceded byCharles Tatgenhorst Jr.Succeeded byHerbert S. BigelowIn officeJanuary 3, 1939 – January 3, 1949Preceded byHerbert S. BigelowSucceeded byEarl T. WagnerIn officeJanuary 3, 1951 – January 3, 1961Preceded byEarl T. WagnerSucceeded byDonald D. Clancy Personal detailsBorn(1898-02-13)February ...

Voce principale: DFL-Ligapokal. DFB-Ligapokal 1999Coppa di Lega tedesca 1999 Competizione DFL-Ligapokal Sport Calcio Edizione 4ª Organizzatore DFB Date dal 10 luglio 1999al 17 luglio 1999 Luogo Germania Partecipanti 6 Risultati Vincitore Bayern Monaco(3º titolo) Secondo Werder Brema Statistiche Miglior marcatore Ulf Kirsten (Bayer Leverkusen) Sören Seidel (Werder Brema), 2 gol Incontri disputati 5 Gol segnati 14 (2,8 per incontro) Pubblico 63 500 (...

1976 studio album by Fairport ConventionGottle O'GeerStudio album by Fairport ConventionReleasedMay 1976RecordedIsland (London)Sawmills (Cornwall, England) [1]GenreFolk rockLength30:35LabelIslandProducerBruce RowlandFairport Convention chronology Rising for the Moon(1975) Gottle O'Geer(1976) The Bonny Bunch of Roses(1977) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllmusic[2] Gottle O'Geer (credited to Fairport and to Fairport Featuring Dave Swarbrick in the US) is ...

Запрос «Аскетизм» перенаправляется сюда; о понятии в психологии см. Аскетизм (защитный механизм). Аске́за (от др.-греч. ἄσκησις — «упражнение», и др.-греч. ἀσκέω — «упражнять»), или аскети́зм — методика достижения духовных целей через упражнения в самодисциплине, ...

Сельское поселение России (МО 2-го уровня)Новотитаровское сельское поселение Флаг[d] Герб 45°14′09″ с. ш. 38°58′16″ в. д.HGЯO Страна Россия Субъект РФ Краснодарский край Район Динской Включает 4 населённых пункта Адм. центр Новотитаровская Глава сельского пос�...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne s'appuie pas, ou pas assez, sur des sources secondaires ou tertiaires (janvier 2019). Pour améliorer la vérifiabilité de l'article ainsi que son intérêt encyclopédique, il est nécessaire, quand des sources primaires sont citées, de les associer à des analyses faites par des sources secondaires. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Faculté de théologie protestante. Faculté universitaire de ...

Article principal : Comité français de libération nationale. Comité français de libération nationale Informations générales Régime Comité français de libération nationale Chef du gouv. Charles de Gaulle Début 3 juin 1943 Fin 9 septembre 1944 1 an 3 mois et 6 jours Autres gouvernements av. 1942 - août 1944 Gouv. Pierre Laval VI Représentation Législature Aucune, la XVIe ayant voté les pleins pouvoir constituants à Pétain Entités précédentes : Comité national fr...

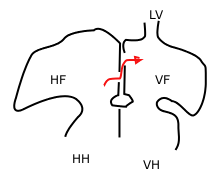

Foramen secundumBlood, shown in the red arrow, travels through the foramen ovale and the foramen secundum. HH: right ventricle, VH: left ventricle, HF: right atrium, VF: left atrium, LV: pulmonary veinDetailsDays33IdentifiersLatinforamen secundumTEsecundum_by_E5.11.1.5.2.1.2 E5.11.1.5.2.1.2 Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] The foramen secundum or ostium secundum is a foramen in the septum primum, a precursor to the interatrial septum of the human heart. It is not the same as the ...

American legal scholar Karl LlewellynBornKarl Nickerson Llewellyn(1893-05-22)May 22, 1893Seattle, Washington, U.S.DiedFebruary 13, 1962(1962-02-13) (aged 68)Chicago, Illinois, U.S.Academic backgroundEducationYale University (LLB, JD)University of LausanneInfluencesArthur L. Corbin, Wesley Newcomb HohfeldAcademic workSchool or traditionLegal realismInstitutionsColumbia Law SchoolUniversity of Chicago Law SchoolNotable worksThe Bramble Bush: On Our Law and Its Study (1930) Karl Nickerson L...

Medical aspect of Romanticism Scene from Goethe's Faust Romantic medicine is part of the broader movement known as Romanticism, most predominant in the period 1800–1840, and involved both the cultural (humanities) and natural sciences, not to mention efforts to better understand man within a spiritual context ('spiritual science').[1] Romanticism in medicine was an integral part of Romanticism in science. Romantic writers were far better read in medicine than we tend to remember: By...

Juneyao Air吉祥航空 IATA ICAO Kode panggil HO DKH AIR JUNEYAO Didirikan2005; 19 tahun lalu (2005)Penghubung Bandar Udara Internasional Hongqiao Shanghai Bandar Udara Internasional Pudong Shanghai Penghubung sekunder Bandar Udara Internasional Lukou Nanjing Program penumpang setiaJuneyao Air ClubAliansiStar Alliance (Terhubung Sesama)[1]Armada88Tujuan70Perusahaan indukJuneyao Group[2]Kantor pusatNo. 80 Hongxiang Sanlu, Distrik Changning,[3] ShanghaiTokoh utamaW...

Artikel ini perlu diterjemahkan dari bahasa Inggris ke bahasa Indonesia. Artikel ini ditulis atau diterjemahkan secara buruk dari Wikipedia bahasa Inggris. Jika halaman ini ditujukan untuk komunitas bahasa Inggris, halaman itu harus dikontribusikan ke Wikipedia bahasa Inggris. Lihat daftar bahasa Wikipedia. Artikel yang tidak diterjemahkan dapat dihapus secara cepat sesuai kriteria A2. Jika Anda ingin memeriksa artikel ini, Anda boleh menggunakan mesin penerjemah. Namun ingat, mohon tidak men...

الاتحاد الدانماركي لكرة القدم الاسم المختصر DBU الرياضة كرة القدم أسس عام 1889 (منذ 135 سنة) الانتسابات الفيفا : 1904 UEFA : 1954 رمز الفيفا DEN الموقع الرسمي www.dbu.dk تعديل مصدري - تعديل تأسس الاتحاد الدنمركي لكرة القدم في عام 1889م وانضم إلى الاتحاد الدولي لكرة القدم في 1904م وان�...

Esta é uma lista com os jogadores de futebol com mais gols em apenas uma temporada. Alguns dos maiores artilheiros de todos os tempos se apresentam na lista. Ranking Jogos Oficiais e Não-Oficiais Notas: Consideram-se aqui todos os jogos com súmula. Assim, jogos oficiais, amistosos, Jogos festivos e jogos pela seleção do exército estão contabilizados. As temporadas no futebol brasileiro iniciam no primeiro mês do ano e terminam no último. Já a temporada no futebol europeu inicia-se n...

Office, Garden, Observation, Restaurant, Retail in Boston, MassachusettsTrans National PlaceRendition of a rejected design for the building by Renzo PianoGeneral informationStatusCancelled[1] and supersededTypeOffice, Garden, Observation, Restaurant, RetailLocation115 Federal Street, Boston, MassachusettsCoordinates42°21′16″N 71°03′25″W / 42.354461°N 71.056957°W / 42.354461; -71.056957Design and constructionArchitect(s)Childs Bertman Tseckares Inc.D...

Trapper Trails CouncilOwnerBoy Scouts of AmericaHeadquarters1200 E 5400 S Ogden, UT 84403CountryUnited StatesCoordinates41°09′54″N 111°56′58″W / 41.165121°N 111.949539°W / 41.165121; -111.949539DefunctApril 2020 Websitehttps://www.trappertrails.org/ Scouting portal The Trapper Trails Council is a former local council of the Boy Scouts of America that served areas in Northern Utah, Southern Idaho and Western Wyoming serving 18 districts. In April 2020,...