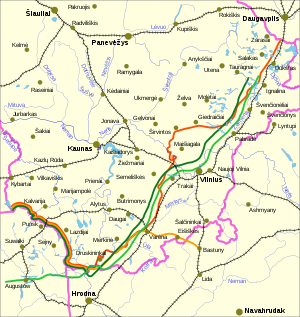

Sejny Uprising

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Las Maitas – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Las MaitasDesaNegara ChiliRegionRegion Arica y Parinacota Las Maitas adalah sebuah desa di Region Arica y Parinacota, Chili. Referensi ...

Information operations to assist military objectives Psyop redirects here. For other uses, see Psyop (disambiguation). Psywar redirects here. For the song by the Norwegian metal band Mayhem, see Psywar (Mayhem song). An example of a World War II era leaflet meant to be dropped from an American B-17 over a German city (see the file description page for a translation) Part of a series onWar History Prehistoric Ancient Post-classical Early modern napoleonic Late modern industrial fourth-gen Mili...

Cubluk umum Romawi ditemukan dalam penggalian Ostia Antica ; tidak seperti instalasi modern, orang Romawi tidak melihat perlunya memberikan privasi bagi pengguna individu. Cubluk (dari bahasa Jawa) atau latrin adalah jamban atau fasilitas yang lebih sederhana yang digunakan sebagai toilet dalam sistem sanitasi . Misalnya saja, cubluk tersebut dapat berupa parit komunal di dalam tanah di sebuah kamp untuk digunakan sebagai sanitasi darurat, sebuah lubang di dalam tanah , atau desain yang ...

Konsonan geser dwibibir bersuaraβꞵNomor IPA127Pengkodean karakterEntitas (desimal)βꞵUnikode (heks)U+03B2 U+A7B5X-SAMPABKirshenbaumBBraille Gambar Sampel suaranoicon sumber · bantuan Konsonan aproksiman dwibibir bersuaraβ̞ʋ̟ Gambar Sampel suaranoicon sumber · bantuan Konsonan geser dwibibir nirsuara adalah jenis dari suara konsonan dwibibir yang digunakan dalam berbagai bahasa. Simbol IPAnya adalah ⟨ɸ⟩. Dalam bahasa Ind...

German artist Georg BaselitzGeorg Baselitz in a photograph by Oliver MarkBorn (1938-01-23) 23 January 1938 (age 86)Deutschbaselitz, GermanyNationalityGerman, AustrianKnown forPainting, sculpture, graphic designMovementNeo-expressionismSpouseJohanna Elke Kretzschmar Georg Baselitz (born 23 January 1938) is a German painter, sculptor and graphic artist. In the 1960s he became well known for his figurative, expressive paintings. In 1969 he began painting his subjects upside down in an ...

American physicist and scientific editor (1913–2004) Philip AbelsonPhilip AbelsonBornApril 27, 1913Tacoma, Washington, United StatesDiedAugust 1, 2004 (aged 91)Bethesda, Maryland, United StatesNationalityAmericanAlma materWashington State UniversityUniversity of California, BerkeleyKnown forDiscovery of neptunium, isotope separation techniquesAwardsKalinga Prize (1972)National Medal of Science (1987)Public Welfare Medal (1992)Vannevar Bush Award (1996)Scientific careerFieldsNuclea...

Indian freedom movement against the British Quit India MovementGandhi discusses the movement with NehruDate1942–1945LocationBritish IndiaParties Indian nationalists British Empire Lead figures Mahatma Gandhi Indian National Congress Prime Minister Winston ChurchillViceroy Lord Linlithgow Casualties and losses British estimates: 1,028 killed[1] 3125 wounded[1]Over 100,000 arrested[2] Congress estimates:4,000–10,000 killed[1][3] 63 officers killed[...

American politician This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Peter Plympton Smith – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) ...

For the parcel of land in Maryland, see Belair Mansion (Bowie, Maryland). For the railway station, see Enfield Chase railway station. Human settlement in EnglandEnfield ChaseEnfield ChaseLocation within Greater LondonLondon boroughEnfieldCeremonial countyGreater LondonRegionLondonCountryEnglandSovereign stateUnited KingdomPost townENFIELDPostcode districtEN2PoliceMetropolitanFireLondonAmbulanceLondon London AssemblyEnfield and Haringey List of places UK England London...

Battle of the Second Italian War of Independence Battle of MagentaPart of the Second Italian War of IndependenceThe Battle of Magenta by Gerolamo Induno, 1861(Musée de l'Armée, Paris)Date4 June 1859[1]LocationMagenta, Austrian Empire (present-day Italy)45°27′22″N 8°48′7″E / 45.45611°N 8.80194°E / 45.45611; 8.80194Result Franco-Italian victoryBelligerents France Sardinia AustriaCommanders and leaders Napoleon III Patrice de MacMahon Ferenc Gy...

Dieser Artikel oder nachfolgende Abschnitt ist nicht hinreichend mit Belegen (beispielsweise Einzelnachweisen) ausgestattet. Angaben ohne ausreichenden Beleg könnten demnächst entfernt werden. Bitte hilf Wikipedia, indem du die Angaben recherchierst und gute Belege einfügst. Emanuel Haldeman-Julius Emanuel Haldeman-Julius (* 30. Juli 1889 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; † 31. Juli 1951), geboren als Emanuel Julius, war ein sozialistischer Reformer und Verleger jüdischer Abstammung. Sech...

Municipality in Southeast, BrazilSão Pedro da UniãoMunicipalitySão Pedro da UniãoLocation in BrazilCoordinates: 21°7′37″S 46°36′54″W / 21.12694°S 46.61500°W / -21.12694; -46.61500Country BrazilRegionSoutheastStateMinas GeraisMesoregionSul/Sudoeste de MinasPopulation (2020 [1]) • Total4,610Time zoneUTC−3 (BRT) São Pedro da União is a municipality in the state of Minas Gerais in the Southeast region of Brazil.[2&#...

American lawyer & politician (born 1958) Xavier BecerraOfficial portrait, 202125th United States Secretary of Health and Human ServicesIncumbentAssumed office March 19, 2021PresidentJoe BidenDeputyAndrea PalmPreceded byAlex Azar33rd Attorney General of CaliforniaIn officeJanuary 24, 2017 – March 18, 2021GovernorJerry BrownGavin NewsomPreceded byKamala HarrisSucceeded byRob BontaMember of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom CaliforniaIn officeJanuary 3, 1993 �...

Bilateral relationsTurkish–American relations Turkey United States Diplomatic missionEmbassy of Turkey, Washington, D.C.Embassy of the United States, AnkaraEnvoyTurkish Ambassador to the United States Sedat ÖnalAmerican Ambassador to Turkey Jeff Flake The Republic of Turkey (Türkiye) and the United States of America established diplomatic relations in 1927. Relations after World War II evolved from the Second Cairo Conference in December 1943 and Turkey's entrance into World War II on th...

1996 studio album by AsiaArenaStudio album by AsiaReleased4 March 1996Recorded1995StudioElectric Palace, LondonGenreProgressive rockLength63:54LabelBullet ProofProducerJohn PayneGeoff DownesAsia chronology Aria(1994) Arena(1996) Archiva 1(1996) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllMusic[1] Arena is the sixth studio album by British rock band Asia, released in March 1996 by Bullet Proof Records. Recorded at Electric Palace Studios in London during 1995, it was produ...

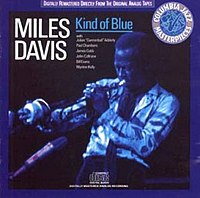

For other uses, see Kind of Blue (disambiguation). 1959 studio album by Miles DavisKind of BlueStudio album by Miles DavisReleasedAugust 17, 1959 (1959-08-17)RecordedMarch 2 and April 22, 1959StudioColumbia 30th Street (New York City)GenreModal jazzLength45:44LabelColumbiaProducerIrving TownsendMiles Davis chronology Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants(1959) Kind of Blue(1959) Jazz Track(1959) Kind of Blue is a studio album by the American jazz trumpeter and composer...

Sport tournament 2015 Men's Junior World Handball ChampionshipTournament detailsHost country BrazilVenue(s)2 (in 2 host cities)Dates19 July – 1 August 2015Teams24 (from 4 confederations)Final positionsChampions France (1st title)Runner-up DenmarkThird place GermanyFourth place EgyptTournament statisticsMatches played92Goals scored5,250 (57.07 per match)Top scorer(s) Nicusor Negru(70 goals)[1]Best player Florian Delecroix[2]&#...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع فرارة (توضيح). فرارة علم شعار الاسم الرسمي (بالإيطالية: Ferrara) الإحداثيات 44°50′07″N 11°37′12″E / 44.835297°N 11.619865°E / 44.835297; 11.619865 [1] تقسيم إداري البلد إيطاليا (20 سبتمبر 1870–)[2][3] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة فرارة (18...

Serie C 1935-1936 Competizione Serie C Sport Calcio Edizione 1ª Organizzatore Direttorio Divisioni Superiori Date dal 22 settembre 1935al 31 maggio 1936 Luogo Italia Partecipanti 64 Formula 4 gironi A/R Risultati Promozioni CremoneseSpeziaVeneziaCatanzarese Retrocessioni (le squadre scritte in corsivo sono poi state riammesse) Montevarchi, Casale; Comense, Empoli;Fermana, Pescara; Cagliari, Trento;Ventimigliese, Forlimpopoli;Grion Pola, Libertas Rimini; Legnano, Gallaratese;Cu...

Miniatura fiamminga di fine Quattrocento La signoria fondiaria era una forma di potere locale esercitata dai grandi proprietari terrieri nei secoli centrali del Medioevo. Viene detta fondiaria in quanto trae origine dai possedimenti fondiari, sui quali il signore esercita il proprio potere. Indice 1 Storia 1.1 Origini e contesto storico 1.2 Sviluppo del potere signorile 1.3 Nascita della signoria di banno 2 Descrizione 2.1 Gestione della grande signoria 2.1.1 Signorie religiose 2.1.2 Signorie...