Rudolf Leopold

|

Read other articles:

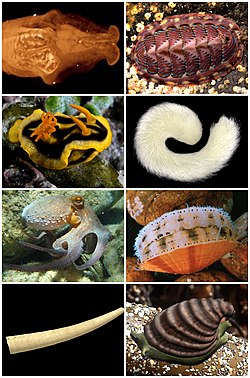

Moluska Mollusca TaksonomiSuperkerajaanEukaryotaKerajaanAnimaliaSuperfilumLophotrochozoaFilumMollusca Cuvier, 1797 Diversitas 85.000 spesies hidup yang diketahui.[1] KelasCaudofoveata Aplacophora Polyplacophora Monoplacophora Bivalvia (kerang-kerangan) Scaphopoda Gastropoda (siput-siputan) Cephalopoda (gurita, cumi-cumi, dan sotong) † Rostroconchia † Helcionelloida † ?Bellerophontidalbs Moluska (Mollusca, dari bahasa Latin: molluscus = lunak) merupakan hewan triploblastik s...

Kereta Bawah Tanah Metropolitan SeoulInfoPemilikPemerintah Korea Selatan, Pemerintah Metropolitan Seoul, Incheon, Bucheon, Uijeongbu, YonginWilayahSeoul, Korea SelatanIncheon, Gyeonggi-do, Chungcheongnam-do, Gangwon-doJenisAngkutan cepatJumlah jalur23Jumlah stasiun640Penumpang tahunan1,91 miliar (2017, Jalur 1-9 Seoul Subway)[1]1,16 miliar (2017, Korail)OperasiDimulai15 Agustus 1974; 49 tahun lalu (1974-08-15)OperatorSeoul Metro, Seoul Metropolitan Rapid Transit Corporation, Kora...

Stasiun Yashū-Ōtsuka野州大塚駅Stasiun Yashū-Ōtsuka pada Agustus 2021Lokasi1258-10 Ōtsuka-machi, Tochigi-shi, Tochigi-ken, 328-0007JepangKoordinat36°24′31″N 139°46′21″E / 36.4086°N 139.7724°E / 36.4086; 139.7724Koordinat: 36°24′31″N 139°46′21″E / 36.4086°N 139.7724°E / 36.4086; 139.7724Operator Tobu RailwayJalur■ Jalur Tobu UtsunomiyaJumlah peron1 peron sampingInformasi lainKode stasiunTN-32Situs webSitus web r...

For the community formerly known by the same name, see St. Lewis, Newfoundland and Labrador. Town in Newfoundland and Labrador, CanadaFox HarbourTownFox Harbour at Sunset, Summer 2009Fox HarbourLocation of Fox HarbourShow map of NewfoundlandFox HarbourFox Harbour (Canada)Show map of CanadaCoordinates: 47°19′17″N 53°52′58″W / 47.32139°N 53.88278°W / 47.32139; -53.88278CountryCanadaProvinceNewfoundland and LabradorSettledearly 1800sIncorporated1964Population&...

Iroquois Seneca religious leader This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Handsome LakeDrawing by Jesse CornplanterBornHadawa'ko1735CanawaugusDiedAugust 10, 1815 (aged 79–80)NationalitySenecaOther namesSganyadái:yo; Sganyodaiyo; Θkanyatararí•yau•; Skanatalihyo; Gan...

Football clubViitorul Minerul LupeniFull nameClubul Sportiv Viitorul Minerul LupeniNickname(s)Minerii (The Miners)Roș-negrii (The Red-Blacks])Founded1920; 104 years ago (1920) as Jiul Lupeni 2021; 3 years ago (2021) as Viitorul Minerul LupeniGroundMinerulCapacity5,000OwnerLupeni MunicipalityChairmanEmil LumperdeanManagerDan VoicuLeagueLiga IV2022–23Liga IV, Hunedoara, 2nd of 11 Home colours Away colours Clubul Sportiv Viitorul Minerul Lupeni, commonly kn...

JinhoNama asal조진호LahirJo Jin-ho17 April 1992 (umur 32)Daejeon, Korea SelatanNama lainJinoPekerjaanPenyanyipenarikomponispembuat lirikKarier musikGenre K-pop elektronik dansa-pop Tahun aktif2010–sekarangLabelSMCubeArtis terkaitPentagonSM the BalladUnited CubeNama KoreaHangul조진호 Hanja趙珍虎 Alih AksaraJo Jin-hoMcCune–ReischauerCho ChinhoNama panggungHangul진호 Hanja珍虎 Alih AksaraJin-hoMcCune–ReischauerChinho Jo Jin-ho (조진호), yang dikenal dengan m...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant une compétition cycliste et la Belgique. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Gand-Wevelgem fémininNom officieldepuis 2012 Gent-WevelgemGénéralitésSport Cyclisme sur routeCréation 2012Nombre d'éditions 13 (en 2024)Périodicité annuelle (mars)Type / Format Course d'un jourLieu(x) BelgiqueCatégories 1.2 (2014-2015)1.WWT (depuis 2016)Circuit UCI World Tour...

Artikel ini membutuhkan rujukan tambahan agar kualitasnya dapat dipastikan. Mohon bantu kami mengembangkan artikel ini dengan cara menambahkan rujukan ke sumber tepercaya. Pernyataan tak bersumber bisa saja dipertentangkan dan dihapus.Cari sumber: Ja'far ash-Shadiq – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Ja'far ash-ShadiqJa'far ash-Shadiq Radhiyallahu AnhuKun-yahAbu AbdillahNamaJa'far ash-ShadiqKebangsaanUmayyah, Abbasiyah Bagian dari seri ...

Katedral Santo Gallus dan Othmar, St. Gallen Ini adalah daftar katedral di Swiss diurutkan berdasarkan denominasi. Katolik Katedral Santo Nikolas, Fribourg Katedral Gereja Katolik di Swiss:[1] Katedral Santo Ursus dan Victor, Solothurn Katedral Basilika Maria Diangkat ke Surga, Chur Katedral Santo Nikolas, Fribourg Katedral Santo Laurensius, Lugano Katedral Biara Benediktin Santo Mauritius, Einsiedeln Katedral Biara Santo Mauritius, Saint-Maurice-d'Agaune Katedral Santo Gall dan Otmar...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

محمود أبو زيد معلومات شخصية تاريخ الميلاد 7 مايو 1941(1941-05-07) الوفاة 11 ديسمبر 2016 (75 سنة)القاهرة الجنسية مصري الأولاد كريم أبو زيد الحياة العملية المهنة كاتب سيناريو، وكاتب المواقع IMDB صفحته على IMDB السينما.كوم صفحته على السينما.كوم بوابة الأدب تعديل مصدري - تعديل...

American TV series or program DeVanitySeason 3 title cardCreated byMichael CarusoWritten byMichael CarusoDirected byKelley PortierStarringMichael CarusoAlexis ZibolisKatie CaprioMike DirksenErin BuckleyKatie ApicellaChris ParkeKyle LowderJason ChristopherJaclyn LyonsJohn BrodyCountry of originUnited StatesOriginal languageEnglishNo. of seasons4No. of episodes28 (list of episodes)ProductionExecutive producerMichael CarusoProducersBarbara Caruso (co-exec)Kelley PortierProduction companyCaruso/...

1980s military camouflage pattern U.S. Woodland Digitized swatch of the U.S. Woodland patternTypeMilitary camouflage patternPlace of originUnited StatesService historyIn service 1981–2012 (U.S. military) 2006-present (MARSOC) Used bySee Users (for other non-U.S. users)WarsInvasion of Grenada United States invasion of Panama Lebanese Civil War Somali Civil War Colombian conflict Yugoslav Wars Operation Uphold Democracy War in Afghanistan Iraq War 2008 Cambodian-Thai stand...

Questa voce sull'argomento atleti statunitensi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Shalonda SolomonShalonda Solomon ai campionati nazionali statunitensi 2010Nazionalità Stati Uniti Altezza169 cm Peso56 kg Atletica leggera SpecialitàVelocità SocietàAdidas Record 60 m 715 (indoor - 2011) 100 m 1090 (2010) 200 m 2215 (2011) 200 m 2257 (indoor - 2006) 400 m 5283 (2016) 400 m 5473 (indo...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с такой фамилией, см. Хохлов; Хохлов, Николай.Николай Иванович Хохлов Дата рождения 1891[1] Место рождения Москва, Российская империя Дата смерти 1953[1] Место смерти Москва, СССР Гражданство (подданство) Российская империя С...

Unincorporated community in Pennsylvania, United StatesGarnet Valley, PennsylvaniaUnincorporated communityGarnet ValleyLocation of Garnet Valley in PennsylvaniaShow map of PennsylvaniaGarnet ValleyGarnet Valley (the United States)Show map of the United StatesCoordinates: 39°51′30″N 75°28′07″W / 39.85833°N 75.46861°W / 39.85833; -75.46861CountryUnited StatesStatePennsylvaniaCountyDelawareTownshipsBethelTownship City2006Population (2010) • T...

COGAM Colectivo de Lesbianas, Gays, Transexuales, Bisexuales e Intersexuales de Madrid Acrónimo COGAMTipo Organización no gubernamentalCampo Derechos LGBTFundación 29 de septiembre de 1986Sede central Madrid, España Calle, Puebla, 9 (Metro, estaciones de Gran Vía, Callao, Tribunal.) Teléfono: 915 23 00 70Área de operación Comunidad de MadridPersonas clave Ronny de la Cruz Presidente , Carmen García de Merlo , Boti García Rodrigo expresidentas. Pedro Zerolo, Miguel Ángel Sánchez ex...

Mida è un nome proprio di persona italiano maschile[1][2][3][4]. Indice 1 Varianti in altre lingue 2 Origine e diffusione 3 Onomastico 4 Persone 5 Il nome nelle arti 6 Note 7 Bibliografia Varianti in altre lingue Greco antico: Μίδας (Midas)[5] Inglese: Midas[6] Latino: Midas[1] Origine e diffusione Re Mida, di Andrea Vaccaro Continua il nome greco antico Μίδας (Midas); sebbene alcune fonti lo ricolleghino al termine greco mìd...

Electrical circuit with active components The die from an Intel 8742, an 8-bit microcontroller that includes a CPU, 128 bytes of RAM, 2048 bytes of EPROM, and I/O data on current chip. A circuit built on a printed circuit board (PCB). An electronic circuit is composed of individual electronic components, such as resistors, transistors, capacitors, inductors and diodes, connected by conductive wires or traces through which electric current can flow. It is a type of electrical circuit. For a ci...