Phil Karlson

| |||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Orang Vietnam di Jepang在日ベトナム人Người Việt ở NhậtJumlah populasi371.755 (Juni 2019)[1]Daerah dengan populasi signifikanTokyo, Osaka (Ikuno-ku), Yokohama, Kobe(Nagata-ku, Hyogo-ku)BahasaJepang, VietnamAgamaBuddha,[2][3] Katolik[4]Kelompok etnik terkaitOrang Vietnam Orang Vietnam di Jepang (在日ベトナム人code: ja is deprecated , Zainichi Betonamujin, Người Việt ở Nhật) menjadi komunitas penduduk asing ketiga terbesar di Jepang...

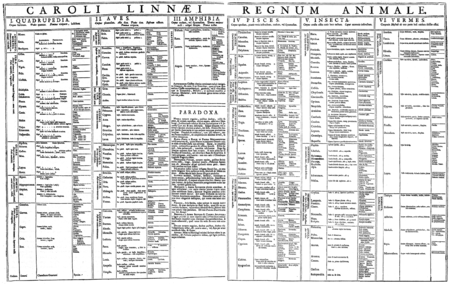

Major work by Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus Systema Naturæ Title page of the 1758 edition of Linnaeus's Systema Naturæ.[1]AuthorCarl Linnaeus(Carl von Linné)CountrySwedenSubjectTaxonomyGenreBiological classificationPublication date1735 (1735)LC ClassQH43 .S21 Systema Naturae (originally in Latin written Systema Naturæ with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaea...

Mexican wireless operator ClaroCompany typeSubsidiaryIndustryWireless servicesFounded19 September 2003;20 years ago (2003-09-19) São Paulo, BrasilHeadquartersMexico City, MexicoNumber of locations List Argentina Brazil Chile Colombia Costa Rica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Puerto Rico Uruguay Key peopleManola Ayala-CEOCarlos J. García Moreno-CFOCarlos Cárdenas-Exec LatAm OperationsServicesUMTS/HSDPA, CDMA, GSM, AMPS,...

British educational certification For the film, see A Level (film). Advanced Level (A-level)GCE Advanced Level logo by University of Cambridge International ExaminationsAcronymA-levelTypeGeneral Certificate of EducationYear started1951Duration2 yearsLanguagesEnglish language, Welsh languagePrerequisites / eligibility criteriaTypically General Certificate of Secondary Education The A-level (Advanced Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Educati...

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Longton, Staffordshire kota kecil Longton, StaffordshireTempat Negara berdaulatBritania RayaNegara konstituen di Britania RayaInggrisRegion di InggrisWest MidlandsProvinsi di InggrisStaffordshireUnitary authority area in England (en)City of Stoke-on-Trent (en) NegaraBritania Raya Informasi tambahanKode posST3 Zona wakt...

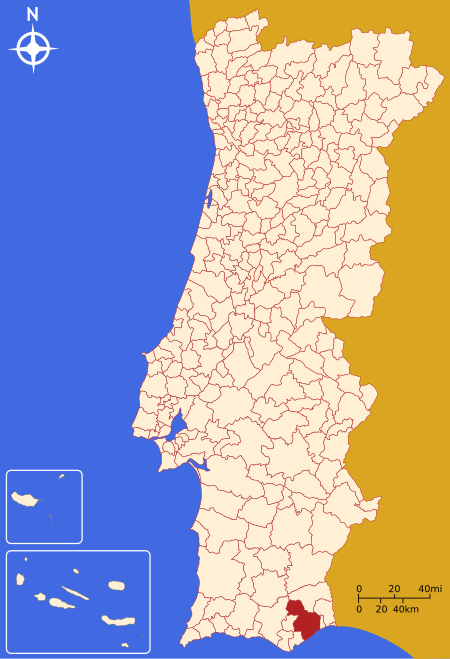

Tavira atau Tabira adalah nama lain Durango, Spain. TaviraView of Tavira BenderaLambangregionAlgarvesubregionAlgarvedistrictFaroLuas • Total607,17 km2 (23,443 sq mi)Populasi (2001) • Total24.995 • Kepadatan0,41/km2 (1,1/sq mi)Situs webwww.cm-tavira.pt/ Letak Tavira di Portugal Tavira (pengucapan bahasa Portugis: [tɐˈviɾɐ]) merupakan nama kota di Portugal. Letaknya di bagian selatan. Tepatnya di Distrik Faro, region Algarve,...

Any neurological disease in which the myelin sheath of neurons is damaged Medical conditionDemyelinating diseasePhotomicrograph of a demyelinating MS-lesion: Immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlights numerous macrophages (brown). Original magnification 10×.SpecialtyNeurology A demyelinating disease refers to any disease affecting the nervous system where the myelin sheath surrounding neurons is damaged.[1] This damage disrupts the transmission of signals through the affe...

Ini adalah nama Melayu; nama Mohd Yusoff merupakan patronimik, bukan nama keluarga, dan tokoh ini dipanggil menggunakan nama depannya, Siti Zailah. Yang BerhormatSiti Zailah Mohd Yusof Anggota Parlemen Malaysiadapil Rantau Panjang, KelantanPetahanaMulai menjabat 2008 Informasi pribadiPartai politikPAS–Pakatan RakyatPekerjaanPolitikusSitus webhttp://sitizailah.blogspot.com/Sunting kotak info • L • B Siti Zailah Mohd Yusoff adalah seorang politikus Malaysia dan Anggota Parle...

This article is about the town in England. For the town in Canada, see Godmanchester, Quebec. Human settlement in EnglandGodmanchesterPost Street in Godmanchester, with the tower of St Mary's ChurchGodmanchesterLocation within CambridgeshireArea1.983 km2 (0.766 sq mi) civil parishPopulation7,893 (2021)• Density3,980/km2 (10,300/sq mi)OS grid referenceTL245704• London56 miles (90 km)Civil parishGodmanchester [1]DistrictHuntingd...

Artikel ini bukan mengenai Nonana atau Nonuna. Nonena adalah sebuah alkena dengan rumus molekul C9H18. Banyak isomer struktural nonena yang mungkin terjadi, bergantung pada lokasi ikatan rangkap C=C dan percabangan bagian lain dari molekulnya. Secara industri, nonena yang paling penting adalah trimer dari propena: Tripropilena. Campuran nonena bercabang ini digunakan dalam alkilasi fenol untuk menghasilkan nonilfenol, sebuah prekursor detergen, yang juga merupakan polutan kontroversial.[1...

Cyclingat the XVI Paralympic GamesPictograms for road (left) and track (right) cyclingVenueIzu Velodrome (track cycling) Fuji Speedway (road cycling)Dates25 August – 3 September 2021Competitors230 in 51 events from 44 nations←20162024→ Cycling at the2020 Summer ParalympicsRoad cyclingRoad racemenwomenTime trialmenwomenTeam relaymixedTrack cyclingTime trialmenwomenIndividual pursuitmenwomenTeam sprintmixedvte Cycling at the2020 Summer ParalympicsRoad time trialMenWomenBBH1H1�...

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府...

الجماعة الإسلامية في جنوب شرق آسيا التأسيس التنظيم الحلفاء القاعدة تعديل مصدري - تعديل الجماعة الإسلامية في جنوب شرق آسيا[1] هي منظمة إسلامية مسلحة في جنوب شرق آسيا تهدف إلى إنشاء دولة إسلامية في جنوب شرق آسيا، تضم هذه الدولة إندونيسيا وماليزيا وجنوب الفلبين وس�...

U.S. Space Force unit 3rd Combat Training SquadronSquadron emblemActive3 March 2022 – presentCountry United StatesBranch United States Space ForceTypeSquadronRoleCombat TrainingSizeSquadronPart ofSpace Delta 3HeadquartersPeterson Space Force Base, Colorado, U.S.Nickname(s)WarriorsMotto(s)Warriors First!CommandersCommanderLt Col Christopher M. HigginsInsigniaFormer 721st Operations Support Squadron patchMilitary unit The 3rd Combat Training Squadron (3 CTS) is a United States ...

Large-scale conflict in South America (1864–1870) Paraguayan WarFrom top, left to right: the Battle of Riachuelo (1865), the Battle of Tuyutí (1866), the Battle of Curupayty (1866), the Battle of Avay (1868), the Battle of Lomas Valentinas (1868), the Battle of Acosta Ñu (1869), the Palacio de los López during the occupation of Asunción (1869), and Paraguayan war prisoners (c. 1870)Date13 November 1864[1] – 1 March 1870(5 years, 3 months, 2 weeks and 2 days...

Family of mammals CanidsTemporal range: Late Eocene-Holocene[1]: 7 ~37.8–0 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N 10 of the 13 extant canid genera Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Infraorder: Cynoidea Family: CanidaeFischer de Waldheim, 1817[2] Type genus CanisLinnaeus, 1758 Subfamilies and extant genera †Prohesperocyon †Hesperocyoninae †Borophaginae Caninae Canidae (/ˈkæ...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Saco. Cet article est une ébauche concernant une localité du Maine. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. SacoNom officiel (en) SacoNom local (en) SacoGéographiePays États-UnisÉtat MaineComté comté de YorkSuperficie 136,64 km2 (2010)Surface en eau 27,1 %Altitude 20 mCoordonnées 43° 30′ 38″ N, 70° 26′ 42�...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Бруно.Бруноангл. Bruneau River Характеристика Длина 246 км Бассейн 8560 км² Расход воды 11 м³/с Водоток Исток (Т) • Координаты 41°34′42″ с. ш. 115°24′50″ з. д.HGЯO Устье (Т) Снейк • Высота[?] 749[1...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع لا غرانغ (توضيح). لا غرانغ الإحداثيات 29°54′30″N 96°52′30″W / 29.9083°N 96.875°W / 29.9083; -96.875 [1] تاريخ التأسيس 1837 تقسيم إداري البلد الولايات المتحدة[2][3] التقسيم الأعلى مقاطعة فاييت عاصمة لـ مقاطعة فاييت خصائص ج�...

Swiss peace activist Pierre CérésoleBorn(1879-08-17)17 August 1879Lausanne, SwitzerlandDied23 October 1945(1945-10-23) (aged 66)Lutry, SwitzerlandNationalitySwissOccupation(s)Engineer, teacher, peace activistKnown forFounder of Service Civil InternationalSignature Pierre Cérésole or Ceresole[a] (17 August 1879 – 23 October 1945) was a Swiss pacifist, remembered for founding the peace organisation Service Civil International (SCI) and the international workcamp mov...