Palace of Whitehall

| |||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

SevillaNama lengkapSevilla Fútbol Club S.A.D.JulukanLos Nervionenses/Los PalanganasNama singkatSFCBerdiri25 Januari 1890; 134 tahun lalu (1890-01-25) yang diakui oleh LFP, UEFA, dan FIFA[1][2][3][4]sebagai Sevilla Foot-ball ClubStadionRamón Sánchez Pizjuán(Kapasitas: 42.714[5])PemilikSevillistas de NervionRafael Carrión MorenoPresiden José María del Nido CarrascoPelatih kepala Quique Sánchez Flores LigaLa Liga2022–2023La Liga, ke-12 dari ...

Cornelia Cinna minorCornelia from Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, dengan tulisan cornelia sinnae [filia] c[ai] caes[aris] vx[or], atau Cornelia, [putri] Cinna, istri G[aius] Caes[ar].LahirKira-kira 97 SMRomaMeninggalKira-kira 69 SM (usia 28)RomaDikenal atasIstri pertama atau kedua dari Yulius KaisarSuami/istriYulius Kaisar (84–69 SM; Cornelia meninggal)AnakJulia (76–54 SM)Orang tuaLucius Cornelius Cinna (bapak)Annia (ibu) Cornelia (c. 97 – c. 69 SM) adalah istri pertama atau kedua Yuli...

American historian (born 1960) Douglas BrinkleyBrinkley in 2023Born (1960-12-14) December 14, 1960 (age 63)Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.OccupationHistorianAlma materOhio State University (BA)Georgetown University (MA, PhD)GenreNonfiction Douglas Brinkley (born December 14, 1960) is an American author, Katherine Tsanoff Brown Chair in Humanities,[1] and professor of history at Rice University. Brinkley is a history commentator for CNN, Presidential Historian for the New York Histori...

Charity Shield FA 1929TurnamenCharity Shield FA English Professionals XI English Amateurs XI 3 0 Tanggal7 Oktober 1929StadionThe Den, London← 1928 1930 → Charity Shield FA 1929 adalah pertandingan sepak bola antara English Professionals XI dan English Amateurs XI yang diselenggarakan pada 7 Oktober 1929 di The Den, London. Pertandingan ini merupakan pertandingan ke-16 dari penyelenggaraan Charity Shield FA. Pertandingan ini dimenangkan oleh English Professionals XI dengan skor 3�...

Artikel ini membutuhkan rujukan tambahan agar kualitasnya dapat dipastikan. Mohon bantu kami mengembangkan artikel ini dengan cara menambahkan rujukan ke sumber tepercaya. Pernyataan tak bersumber bisa saja dipertentangkan dan dihapus.Cari sumber: Limfosit – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR LimfositGambar Transmisi mikroskop electron Limfosit manusia.RincianSistemSistem imunFungsiSel darah putihPengidentifikasiBahasa Latinlymphocytes b...

For the equivalent men's tournament, see 2024 FIBA 3x3 Asia Cup – Men's tournament. 2024 FIBA 3x3 Asia Cup – Women's tournamentTournament detailsHost countrySingaporeCitySingaporeDates27–31 MarchTeams20Venue(s)Singapore Sports Hub OCBC SquareFinal positionsChampions Australia (4th title)Runners-up New ZealandThird place MongoliaFourth place Chinese Taipei← 2023 2025 → The 2024 FIBA 3x3 Asia Cup – Women's tournament was the seventh edition of this conti...

Land features of Western Sahara This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Geography of Western Sahara – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Geography of Western SaharaContinentAfricaRegionNorth AfricaCoordinates24°30′N 13°00�...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Drusus. Julius Caesar DrususJulius Caesar Drusus.FonctionsSénateur romainQuesteurConsulBiographieNaissance 7 octobre 13 av. J.-C.RomeDécès 14 septembre 23 (à 34 ans)RomeSépulture Mausolée d'AugusteNom dans la langue maternelle Nero Claudius Drusus ou Drusus Julius CaesarNom de naissance Nero Claudius DrususSurnom CastorÉpoque Haut Empire romainActivités Homme politique, militaireFamille Julio-Claudiens, Claudii Nerones, Julii CaesarPère Tibère...

Prasasti pada Basilika Agung Santo Yohanes Lateran, tertulis: Indulgentia-plenaria perpetua quotidiana toties quoties pro vivis et defunctis (Indulgensi-penuh tiada berkesudahan setiap hari pada setiap kesempatan bagi orang yang hidup dan mati) Dalam ajaran Gereja Katolik, indulgensi (Inggris: indulgence, bahasa Latin: indulgentia) adalah penghapusan hukuman atau siksa dosa sementara (temporal) karena dosa-dosa yang telah mendapat ampunan. Pada praktiknya indulgensi berhubungan erat d...

Major League Baseball season Major League Baseball team season 1967 Boston Red SoxAmerican League ChampionsLeagueAmerican LeagueBallparkFenway ParkCityBoston, MassachusettsRecord92–70 (.568)League place1stOwnersTom YawkeyPresidentTom YawkeyGeneral managersDick O'ConnellManagersDick WilliamsTelevisionWHDH-TV Channel 5RadioWHDH-AM 850(Ken Coleman, Ned Martin, Mel Parnell)StatsESPN.comBB-reference ← 1966 Seasons 1968 → The 1967 Boston Red Sox season was the 67th seas...

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (March 2017) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Uns...

Love or MoneyPoster rilis resmiSutradaraMae Cruz-AlviarProduser John Leo Garcia Carmi Raymundo SkenarioCrystal Hazel San MiguelPemeran Coco Martin Angelica Panganiban Penata musikFrancis ConcioSinematograferNoel TeehankeePenyuntingMarya IgnacioPerusahaanproduksiStar CinemaCCM Film ProductionsDistributorCineExpressTanggal rilis 12 Maret 2021 (2021-03-12) Durasi116 menitNegaraFilipinaBahasaFilipino Love or Money adalah sebuah film komedi romantis Filipina tahun 2020 yang ditayangkan ...

此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充。 (2021年5月6日)若您熟悉来源语言和主题,请协助参考外语维基百科扩充条目。请勿直接提交机械翻译,也不要翻译不可靠、低品质内容。依版权协议,译文需在编辑摘要注明来源,或于讨论页顶部标记{{Translated page}}标签。 约翰斯顿环礁Kalama Atoll 美國本土外小島嶼 Johnston Atoll 旗幟颂歌:《星條旗》The Star-Spangled Banner約翰斯頓環礁�...

اللغة الجيلاكية الاسم الذاتي گیلکی اسم اللغة الگيلكية بخط النستعليق الناطقون 2.4 مليون (2016) الدول إيران بلاد جیلان وبلاد مازندران المنطقة آسيا الكتابة أبجدية عربية + گ چ پ ژ النسب هندية أوروبية لغات هندية أوروبيةلغات هندية إيرانيةلغات إيرانيةلغات إيرانية غربيةلغات شمال غر...

American five-string banjo player (born 1949) This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Tony Trischka – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2016) (Learn how and when to r...

Benedikt Höwedes Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Benedikt HöwedesTanggal lahir 29 Februari 1988 (umur 36)Tempat lahir Haltern, Jerman BaratTinggi 1,87 m (6 ft 1+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain Pemain bertahanKarier junior1994–2000 TuS Haltern2000–2001 SG Herten-Langenbochum2001–2007 Schalke 04Karier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2007–2008 Schalke 04 II 15 (0)2007–2018 Schalke 04 240 (12)2017–2018 → Juventus (pinjaman) 3 (1)2018–2020 Lokomotiv Moscow 35 (3)Tim n...

Gutian Dynasty of Sumer Gutian Dynasty of Sumerc. 2141 BC–c. 2050 BCCapitalAdabCommon languagesGutian language and Sumerian languageGovernmentMonarchy• fl. c. 2141—2138 BC Erridu-pizir (first)• fl. c. 2055—2050 BC Tirigan (last) Historical eraBronze Age• Established c. 2141 BC• Disestablished c. 2050 BC Preceded by Succeeded by Akkadian Empire Third Dynasty of Ur Today part ofIraq The Gutian dynasty (Sumerian: 𒄖𒋾𒌝𒆠, gu-ti-umKI) was a line of ...

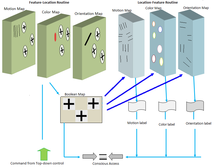

Hal Pashler is Distinguished Professor of Psychology at University of California, San Diego. An experimental psychologist and cognitive scientist, Pashler is best known for his studies of human attentional limitations (his analysis of the Psychological refractory period effect concluded that the brain has discrete processing bottlenecks associated with specific types of cognitive operations).[1][2][3] and for his work on visual attention[4][5] He has al...

Pantestudines Periode Trias Tengah - Holosen, 240–0 jtyl PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N Kemungkinan jejak Permian Tengah[1] Pantestudines dan Pan-Testudines Odontochelys semitestacea TaksonomiKerajaanAnimaliaFilumChordataKelasReptiliaTanpa nilaiPantestudines dan Pan-Testudines Klein, 1760 Subkelompok †Sauropterygia? †Saurosphargidae? †Eunotosaurus? †Acerosodontosaurus? †Claudiosaurus? †Eorhynchochelys †Pappochelys †Odontochelys Testudinata lbs Pantestudines adala...

Chlorophorus figuratus Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Arthropoda Kelas: Insecta Ordo: Coleoptera Famili: Cerambycidae Subfamili: Cerambycinae Tribus: Clytini Genus: Chlorophorus Spesies: Chlorophorus figuratus Chlorophorus figuratus adalah spesies kumbang tanduk panjang yang tergolong familia Cerambycidae. Spesies ini juga merupakan bagian dari genus Chlorophorus, ordo Coleoptera, kelas Insecta, filum Arthropoda, dan kingdom Animalia. Larva kumbang ini biasanya mengebor ke dala...