Paul GuignardPaul GuignardChampion de France des 100 kilomètres sur piste Parc des Princes, 9 juin 1912InformationsNom de naissance Jean-Baptiste Pierre Charles Paul GuignardNaissance 10 mai 1876Ainay-le-ChâteauDécès 15 février 1965 (à 88 ans)18e arrondissement de ParisNationalité françaiseÉquipes professionnelles Clément-DunlopPrincipales victoires Champion du monde de demi-fond 1913 Champion d'Europe de demi-fond 1905, 1906, 1909 et 1912 Champion de France de demi-fond 1905, ...

Tasks in machine learning Part of a series onMachine learningand data mining Paradigms Supervised learning Unsupervised learning Semi-supervised learning Self-supervised learning Reinforcement learning Meta-learning Online learning Batch learning Curriculum learning Rule-based learning Neuro-symbolic AI Neuromorphic engineering Quantum machine learning Problems Classification Generative modeling Regression Clustering Dimensionality reduction Density estimation Anomaly detection Data cleaning...

A Jitney ElopementPoster teatrikal untuk A Jitney ElopementSutradaraCharlie ChaplinProduserJess RobbinsDitulis olehCharlie ChaplinPemeranCharles Chaplin Lloyd Bacon Ernest Van Pelt Edna Purviance Leo WhitePenata musikRobert Israel (perilisan video Kino)SinematograferHarry EnsignPenyuntingCharlie ChaplinDistributorEssanay Studios General Film CompanyTanggal rilis 1 April 1915 (1915-04-01) Durasi33 menitNegaraAmerika SerikatBahasaAntarjudul Inggris Film lengakp A Jitney Elopement ada...

Picco Gugliermina(FR) Pic GuglierminaIl Picco Gugliermina da sud-ovestStato Italia Regione Valle d'Aosta Altezza3 893 m s.l.m. CatenaAlpi Coordinate45°49′14.93″N 6°53′12.44″E45°49′14.93″N, 6°53′12.44″E Data prima ascensione24 agosto 1914 Autore/i prima ascensioneGiovanni Battista Gugliermina e Francesco Ravelli Mappa di localizzazionePicco Gugliermina(FR) Pic Gugliermina Dati SOIUSAGrande ParteAlpi Occidentali Grande SettoreAlpi Nord-occidentali Sezione...

بيرازوليدين Ball-and-stick model of the pyrazolidine molecule Structural formula of pyrazolidine التسمية المفضلة للاتحاد الدولي للكيمياء البحتة والتطبيقية Pyrazolidine أسماء أخرى 1,2-Diazolidine المعرفات رقم CAS 504-70-1 بوب كيم (PubChem) 79033 مواصفات الإدخال النصي المبسط للجزيئات C1CNNC1[1] المعرف الكيميائي الدولي InChI=1S/C3H8N2/c1-2-4...

Philippe SaiveInformasi pribadiKewarganegaraan BelgiaLahir02 Juli 1971 (umur 53)Liège Rekam medali Mewakili Belgia Kejuaraan Dunia Tenis Meja 2001 Men's Team Philippe Saive (lahir 2 Juli 1971) adalah mantan pemain tenis meja internasional pria dari Belgia.[1] Karier tenis meja Dia memenangkan medali perak di Kejuaraan Tenis Meja Dunia 2001 di Piala Swaythling (acara tim putra) dengan Martin Bratanov, Marc Closset, Andras Podpinka, dan Jean-Michel Saive (saudara lelaki...

Artikel ini perlu diwikifikasi agar memenuhi standar kualitas Wikipedia. Anda dapat memberikan bantuan berupa penambahan pranala dalam, atau dengan merapikan tata letak dari artikel ini. Untuk keterangan lebih lanjut, klik [tampil] di bagian kanan. Mengganti markah HTML dengan markah wiki bila dimungkinkan. Tambahkan pranala wiki. Bila dirasa perlu, buatlah pautan ke artikel wiki lainnya dengan cara menambahkan [[ dan ]] pada kata yang bersangkutan (lihat WP:LINK untuk keterangan lebih lanjut...

Wake UpSingel oleh The Vampsdari album Wake UpDirilis2 Oktober 2015Direkam2015GenrePop rock[1]Durasi3:12 (versi album) 5:21 (extended version)LabelMercuryVirgin EMIPenciptaAmmar MalikSteve MacRoss GolanKevin SnevelyProduserSteve MacKronologi singel The Vamps Oh Cecilia (Breaking My Heart) (2014) Wake Up (2015) Rest Your Love (2015) Wake Up adalah lagu dari band pop asal Inggris, The Vamps. Lagu ini dirilis pada 2 Oktober 2015 sebagai single utama dari album studio kedua mereka, W...

КоммунаПеригёфр. Périgueux Герб 45°11′06″ с. ш. 0°43′08″ в. д.HGЯO Страна Франция Регион Аквитания Департамент Дордонь Глава Мишель Мойран[вд] История и география Основан 1240 год Площадь 9,82 км² Высота центра 75—189 м Часовой пояс UTC+1:00, летом UTC+2:00 Население Население 29...

Foram assinalados vários problemas nesta página ou se(c)ção: As fontes não cobrem todo o texto. Precisa ser formatada para o padrão wiki. Sexto Doutor Personagem de Doctor Who Colin Baker como o Sexto Doutor. Informações gerais Primeira aparição The Twin Dilemma (1984) Última aparição The Ultimate Foe (1986) Criado por John Nathan-Turner Interpretado por Colin Baker Período 22 de março de 1984 – 6 de dezembro de 1986 Acompanhantes Peri Brown Melanie Mel Bush Aparições Tempo...

For the TV station that previously held the WTWS callsign, see WHPX-TV. This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: WTWS – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Radio station in Houghton Lake, MichiganWTWSHoughton Lake, MichiganBroadcast area[1]Frequency92.1 MH...

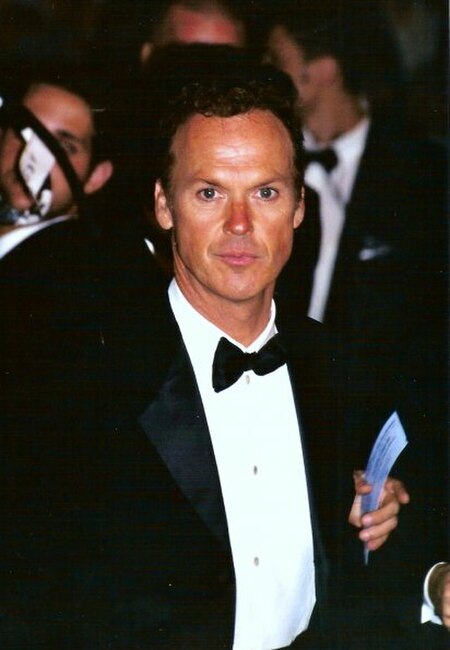

マイケル・キートンMichael Keaton 2024年本名 マイケル・ジョン・ダグラスMichael John Douglas生年月日 (1951-09-05) 1951年9月5日(73歳)出生地 アメリカ合衆国 ペンシルベニア州コラオポリス国籍 アメリカ(スコット・アイリッシュ)職業 俳優・コメディアン・映画監督・プロデューサー活動期間 1977年 -配偶者 キャロライン・マクウィリアムス(英語版)(1982年 - 1990年)主な作�...

Jane Byrne Walikota Chicago ke-50Masa jabatan16 April 1979 – 29 April 1983WakilRichard MellPendahuluMichael BilandicPenggantiHarold Washington Informasi pribadiLahirJane Margaret Burke(1933-05-24)24 Mei 1933Chicago, Illinois, Amerika SerikatMeninggal14 November 2014(2014-11-14) (umur 81)Chicago, Illinois, Amerika SerikatPartai politikPartai DemokratSuami/istriWilliam Byrne (m. 1956; wafat 1959) Jay McMullen ...

American live sports television series This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages) This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. Please help by spinning off or relocating any relevant information, and removing excessive detail that may be against Wikipedia's inclusion policy. (July 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this messag...

1918 German political group of artists The November Group (German: Novembergruppe) was a group of German expressionist artists and architects. Formed on 3 December 1918, they took their name from the month of the German Revolution.[1] The group was led by Max Pechstein and César Klein. Linked less by their styles of art than by shared socialist values, the group campaigned for radical artists to have a greater say in such issues as the organisation of art schools, and new laws around...

مستشفى جينينتان إحداثيات 30°40′09″N 114°16′53″E / 30.66929159°N 114.2814184°E / 30.66929159; 114.2814184 معلومات عامة الدولة الصين سنة التأسيس 2008 معلومات أخرى الموقع الإلكتروني الموقع الرسمي رقم الهاتف +86-27-8636-5341[1] تعديل مصدري - تعديل مستشفى جينينتان (بالصينية: ...

Savignano IrpinoKomuneComune di Savignano IrpinoLokasi Savignano Irpino di Provinsi AvellinoNegaraItaliaWilayah CampaniaProvinsiAvellino (AV)Luas[1] • Total38,47 km2 (14,85 sq mi)Ketinggian[2]718 m (2,356 ft)Populasi (2016)[3] • Total1.163 • Kepadatan30/km2 (78/sq mi)Zona waktuUTC+1 (CET) • Musim panas (DST)UTC+2 (CEST)Kode pos83030Kode area telepon0825Situs webhttp://www.comune.savignan...

1977年(昭和52年)の白鳥貯木場 国土交通省 国土地理院 地図・空中写真閲覧サービスの空中写真を基に作成 白鳥公園内に遺されている太夫堀の一部。左奥は名古屋国際会議場と名古屋学院大学名古屋キャンパス。 白鳥貯木場(しろとり ちょぼくじょう)は、日本の中部地方の、愛知県名古屋市熱田区の堀川沿い(明治中期における愛知郡熱田町内〈熱田白鳥町[* 1 ...

浒墅关站Xushuguan Railway Station浒墅关站站房位置 中华人民共和国江苏省苏州市虎丘区浒墅关镇地理坐标31°23′02″N 120°30′31″E / 31.384021°N 120.508639°E / 31.384021; 120.508639拥有者上海局集团苏州直属站途经线路京沪铁路其他信息车站代码30524[1]电报码XIH[2]拼音码XSG车站等级三等站位置 浒(xǔ)墅关站,是位于中国江苏省苏州市虎丘区的一个铁路�...

Radio station in Glenwood Springs, ColoradoKKCHGlenwood Springs, ColoradoBroadcast areaAspen, ColoradoFrequency92.7 MHzBrandingThe Lift FMProgrammingFormatHot ACOwnershipOwnerPatricia MacDonald Garber and Peter Benedetti(AlwaysMountainTime, LLC)Sister stationsKIFTHistoryFirst air date1997Technical information[1]Licensing authorityFCCFacility ID4360ClassCERP55,200 wattsHAAT763 meters (2,503 ft)Translator(s)94.1 K231AP (Eagle)LinksPublic license information Public fileLMSWebcastLis...