Monty Hall

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Basilika CanilloGereja Basilika Tempat Ziarah Bunda Maria dari MeritxellKatala: santuari de Nostra Senyora de Meritxellcode: ca is deprecated Basilika Canillo, 2013LokasiCanilloNegara AndorraDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaArsitekturStatusBasilika minorStatus fungsionalAktifAdministrasiKeuskupanKeuskupan Urgell Basilika Tempat Ziarah Maria Bunda dari Meritxell (Katala: santuari nou de Meritxellcode: ca is deprecated ) adalah sebuah gereja basilika minor Katolik sekaligus tempat ziarah yang ...

For the suburb in Mount Isa, see The Gap, Queensland (Mount Isa). Map all coordinates using OpenStreetMap Download coordinates as: KML GPX (all coordinates) GPX (primary coordinates) GPX (secondary coordinates) Suburb of Brisbane, Queensland, AustraliaThe GapBrisbane, QueenslandWalton Bridge Reserve at The GapThe GapCoordinates27°26′30″S 152°56′40″E / 27.4416°S 152.9444°E / -27.4416; 152.9444 (The Gap (centre of suburb))Population17,318 (2...

Ana Beatriz BarrosBarros pada 2011Lahir29 Mei 1982 (umur 41)Itabira, Minas Gerais, BrazilPekerjaanModelTahun aktif1996–sekarangSuami/istriKarim El Chiaty (m. 2016)Anak2Informasi modelingTinggi180 m (590 ft 6+1⁄2 in)[1]Warna rambutCoklatWarna mataHijauManajer Next Model Management (New York, Paris, London) Fashion Model Management (Milan) Uno Models (Barcelona) Elite Model Management (Copenhagen, Toronto) Model Management...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir BGP. Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) est un protocole d'échange de route externe (un EGP), utilisé notamment sur le réseau Internet. Son objectif principal est d'échanger des informations de routage et d'accessibilité de réseaux (appelés préfixes) entre Autonomous Systems (AS). Comme il circule sur TCP, il est considéré comme appartenant à la couche application du modèle OSI[1]. Contrairement aux protocoles de routage interne, BGP n'utilise pas de ...

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: Hardware failure following a January 2021 spacewalk,[1] and updates on planned 2020 changes. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (January 2021) A student speaks to crew on the International Space Station using Amateur Radio equipment, provided free by volunteers of the ARISS program.. Astronaut Doug Wheelock operating ham radio from the ISS Amateur Radio on the International Sp...

American entertainment news website Awards DailyType of siteEntertainment newsAvailable inEnglishOwnerSasha StoneFounder(s)Sasha StoneURLawardsdaily.comLaunched1999; 25 years ago (1999)Current statusOnline Awards Daily (formerly known as Oscarwatch) is a website primarily focused on the film industry and the film awards seasons that was established in 1999 by American editor Sasha Stone. History Awards Daily was started in 1999 by Sasha Stone, a writer for entertai...

MontagutoKomuneComune di MontagutoLokasi Montaguto di Provinsi AvellinoNegaraItaliaWilayah CampaniaProvinsiAvellino (AV)Luas[1] • Total18,38 km2 (7,10 sq mi)Ketinggian[2]730 m (2,400 ft)Populasi (2016)[3] • Total451 • Kepadatan25/km2 (64/sq mi)Zona waktuUTC+1 (CET) • Musim panas (DST)UTC+2 (CEST)Kode pos83030Kode area telepon0825Situs webhttp://www.comune.montaguto.av.it Montaguto adalah...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: PASIR IPIS – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR merupakan sebuah bukit yang berada di desa sedong kidul kecamatan sedong kabupaten cirebon diketinggian 800 mdpl pasir ipis terlihat seperti...

Association football championship match between Chelsea and Liverpool, held in 2012 For the women's event, see 2012 FA Women's Cup final. Football match2012 FA Cup finalThe match programme cover, featuring Chelsea’s Didier Drogba and Liverpool's Martin ŠkrtelEvent2011–12 FA Cup Chelsea Liverpool 2 1 Date5 May 2012VenueWembley Stadium, LondonMan of the MatchJuan Mata (Chelsea)[1]RefereePhil Dowd (Staffordshire)[2]Attendance89,102[3]WeatherMostly cloudy9 °C (4...

1969 film by Radley Metzger Camille 2000Original film posterDirected byRadley MetzgerScreenplay byMichael de ForrestBased onLa Dame aux Camélias1852 novelby Alexandre Dumas, filsProduced byRadley MetzgerStarring Danielle Gaubert Nino Castelnuovo Eleonora Rossi-Drago Roberto Bisacco Massimo Serato Silvana Venturelli Philippe Forquet CinematographyEnnio GuarnieriEdited by Humphrey Wood Amedeo Salfa Music byPiero PiccioniProductioncompanySpear ProductionsDistributed by Audubon Films (US) Cinera...

ヨハネス12世 第130代 ローマ教皇 教皇就任 955年12月16日教皇離任 964年5月14日先代 アガペトゥス2世次代 レオ8世個人情報出生 937年スポレート公国(中部イタリア)スポレート死去 964年5月14日 教皇領、ローマ原国籍 スポレート公国親 父アルベリーコ2世(スポレート公)、母アルダその他のヨハネステンプレートを表示 ヨハネス12世(Ioannes XII、937年 - 964年5月14日)は、ロ...

Duke of Connaught redirects here. For ships with this name, see SS Duke of Connaught. Dukedom of Connaughtand StrathearnArms of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (version used from 1874 to 1917)Creation date24 May 1874Created byQueen VictoriaPeeragePeerage of the United KingdomFirst holderPrince ArthurLast holderAlastair WindsorRemainder tothe 1st Duke's heirs male of the body lawfully begottenSubsidiary titlesEarl of SussexStatusExtinctExtinction date26 April 1943 Duke of Conna...

Overview of and topical guide to United States history This article is part of a series on theHistory of the United States Timeline and periodsPrehistoric and Pre-Columbian Erauntil 1607Colonial Era 1607–17651776–1789 American Revolution 1765–1783 Confederation Period 1783–17881789–1815 Federalist Era 1788–1801 Jeffersonian Era1801–18171815–1849 Era of Good Feelin...

Empat kapal induk, Principe de Asturias, USS Wasp, USS Forrestal and HMS Invincible (depan ke belakang). Perbandingan beberapa kapal induk. Kapal induk (bahasa Inggris: aircraft carrier) adalah sebutan untuk kapal perang yang memuat pesawat tempur dalam jumlah banyak. Tugas utamanya adalah memindahkan kekuatan udara ke dalam armada angkatan laut sebagai pendukung operasi-operasi angkatan laut sekaligus sebagai pusat komando operasi dan kekuatan detterence atau memberikan efek gentar pada lawa...

Elezioni regionali in Abruzzo del 2024Stato Italia Regione Abruzzo Data10 marzo Affluenza52,19% ( 0,92%) Candidati Marco Marsilio Luciano D'Amico Partiti Fratelli d'Italia Indipendente Coalizioni Centro-destra Centro-sinistra - M5S Voti 327 66053,50% 284 74846,50% Seggi 18 / 31 13 / 31 Differenza % 5,47% 4,99[A 1]% Differenza seggi 0 0[A 2] Distribuzione del voto per comune Presidente uscenteMarco Marsilio (FdI) 2019 Le elezioni regionali del 2024 in ...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Podger spanner – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) For other uses, see Podger. A podger spanner A podger spanner, or podger, is a tool in the form of a short bar, usually tapered and often incorporating a wrench...

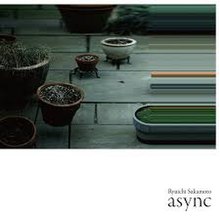

For other uses, see Asynchrony (disambiguation). 2017 studio album by Ryuichi SakamotoasyncStudio album by Ryuichi SakamotoReleasedMarch 29, 2017RecordedApril–December 2016StudioThe Studio; New York CityBastyr University Chapel; Kenmore, WashingtonGermano Studios; New York CityKyoto City University of Arts; KyotoMuseum of Arts and Design; New York CityGateway Mastering; Portland, MaineGenre Electronic[1][2] experimental[3][4][2] ambient[5&...

Voce principale: Prima Divisione 1950-1951. La Prima Divisione fu il massimo campionato regionale di calcio disputato in Piemonte nella stagione 1950-1951. Indice 1 Girone A 1.1 Squadre partecipanti 1.2 Classifica finale 2 Girone B 2.1 Squadre partecipanti 2.2 Classifica finale 3 Girone C 3.1 Squadre partecipanti 3.2 Classifica finale 4 Girone D 4.1 Squadre partecipanti 4.2 Classifica finale 5 Finali regionali 5.1 Verdetti finali 6 Bibliografia 6.1 Giornali 6.2 Libri 7 Voci correlate Girone ...

2022 protest in China You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (October 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia. Do not translate text that ap...

U.S. National Championships 1920Sport Tennis Data30 agosto - 6 settembre (uomini)20 settembre - 25 settembre (donne) Edizione40ª CategoriaGrande Slam (ITF) LocalitàFiladelfia, New York e Chestnut Hill, USA CampioniSingolare maschile Bill Tilden Singolare femminile Molla Bjurstedt Mallory Doppio maschile Bill Johnston / Clarence Griffin Doppio femminile Marion Zinderstein / Eleonora Sears Doppio misto Hazel Wightman / Wallace Johnson 1919 1921 Gli U.S. National Championships 1920 (conosciuti...