Melvin Dummar

| |||||||||

Read other articles:

Lampu era dinasti Han Barat dengan rana geser yang dapat disesuaikan, bertanggal 173 SM, ditemukan di makam Dou Wan. Dou Wan (Hanzi: 竇綰; Pinyin: Dòu Wǎn) adalah istri dari Liu Sheng, Pangeran Zhongshan dari dinasti Han Barat, Tiongkok. Makamnya ditemukan pada tahun 1968 di distrik Mancheng, Hebei. Jasadnya mengenakan jas pemakaman dari giok. Jas giok miliknya dan milik suaminya yang pertama kali ditemukan oleh para arkeolog. Pakaian penguburan ini dibuat untuk melindungi orang-o...

Une guerre souterraine est une guerre menée sous la surface du sol. Aperçu Des soldats de l'armée américaine s'entraînent à la guerre souterraine Les installations militaires souterraines jouent un rôle clé dans de nombreux pays, il existe plus de 10 000 installations militaires souterraines dans le monde, car une telle guerre souterraine est une composante presque inévitable des conflits modernes[1]. Histoire Tunnel souterrain canadien dans le secteur de Vimy, Première Gu...

بيتر نافارو (بالإنجليزية: Peter Kent Navarro) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 15 يوليو 1949 (75 سنة)[1] كامبريدج[1] الإقامة لاغونا بيتش مواطنة الولايات المتحدة الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم جامعة هارفارد (الشهادة:دكتور في الفلسفة)[2]جامعة تافتسكلية كينيدي بجامعة ها...

Nordic and Scandinavian people in the United Kingdom refers to people from the Nordic countries who settled in the United Kingdom, their descendants, history and culture. There has been exchange of populations between Scandinavia and Great Britain at different periods over the past 1,400 years. Over the last couple of centuries, there has been regular migration from Scandinavia to Great Britain, from families looking to settle, businesspeople, academics to migrant workers, particularly those...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Sommeiller. Germain SommeillerGermain SommeillerFonctionsDéputéIXe législature du royaume d'Italie18 novembre 1865 - 13 février 1867Député de la Savoie au Parlement sardeTaninges8 décembre 1853 - 15 novembre 1857François-Marie BastianÉtienne de La FléchèreBiographieNaissance 15 février 1815Saint-Jeoire-en-FaucignyDécès 11 juillet 1871 (à 56 ans)Saint-Jeoire-en-FaucignyNationalité italienneFormation Université de TurinActivités Ingénie...

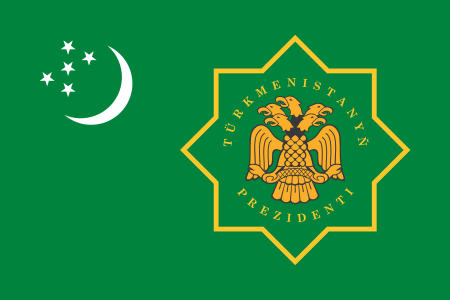

土库曼斯坦总统土库曼斯坦国徽土库曼斯坦总统旗現任谢尔达尔·别尔德穆哈梅多夫自2022年3月19日官邸阿什哈巴德总统府(Oguzkhan Presidential Palace)機關所在地阿什哈巴德任命者直接选举任期7年,可连选连任首任萨帕尔穆拉特·尼亚佐夫设立1991年10月27日 土库曼斯坦土库曼斯坦政府与政治 国家政府 土库曼斯坦宪法 国旗 国徽 国歌 立法機關(英语:National Council of Turkmenistan) ...

Antonov An-70 Vue de l'avion. Rôle Avion cargo Constructeur Antonov Équipage 3 Premier vol 16 décembre 1994 Dimensions Longueur 40,73 m Envergure 44,06 m Hauteur 16,38 m Masse et capacité d'emport Max. à vide 72,8 t Max. au décollage 133 t Passagers 170 soldats Fret 47 t Motorisation Moteurs 4 turbopropulseurs Ivtchenko-Progress D-27 Puissance unitaire 10 300 kW (14 000 ch) Performances Vitesse de croisière maximale 750 km/h Distance f...

烏克蘭總理Прем'єр-міністр України烏克蘭國徽現任杰尼斯·什米加尔自2020年3月4日任命者烏克蘭總統任期總統任命首任維托爾德·福金设立1991年11月后继职位無网站www.kmu.gov.ua/control/en/(英文) 乌克兰 乌克兰政府与政治系列条目 宪法 政府 总统 弗拉基米尔·泽连斯基 總統辦公室 国家安全与国防事务委员会 总统代表(英语:Representatives of the President of Ukraine) 总...

В статье не хватает ссылок на источники (см. рекомендации по поиску). Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть удалена. Вы можете отредактировать статью, добавив ссылки на авторитетные источники в виде сносок. (28 ноября 2018) Процент населения старше 65 лет в ст...

American philosopher (1817–1862) Thoreau redirects here. For other uses, see Thoreau (disambiguation). Henry David ThoreauThoreau in 1856BornDavid Henry Thoreau(1817-07-12)July 12, 1817Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.DiedMay 6, 1862(1862-05-06) (aged 44)Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.Alma materHarvard CollegeEra19th-century philosophyRegionWestern philosophySchoolTranscendentalism[1]Main interestsEthicspoetryreligionpoliticsbiologyphilosophyhistoryNotable ideasAbolitionismtax res...

Philosophical question of whether properties exist and, if so, what they are Boethius teaching his students The problem of universals is an ancient question from metaphysics that has inspired a range of philosophical topics and disputes: Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist beyond those objects? And if a property exists separately from objects, what is the nature of that existence?[1] The problem of universal...

أحمد بن عبد العزيز الزيّات معلومات شخصية الميلاد 1327 هـ - 1907 مالقاهرة مصر الوفاة 2004القاهرة مصر الجنسية مصر الديانة الإسلام أهل السنة والجماعة مشكلة صحية عمى الحياة العملية المهنة قارئ القرآن، وعالم مسلم تعديل مصدري - تعديل فضيلة العلاّمة الشيخ المقرئ أحمد ...

حكومة عصام شرفمعلومات عامةالبلد مصر الاختصاص مصر التكوين 3 مارس 2011 النهاية 7 ديسمبر 2011 المدة 9 أشهرٍ و4 أيامٍوزارة أحمد شفيق وزارة كمال الجنزوري تعديل - تعديل مصدري - تعديل ويكي بيانات وزارة عصام الدين شرف هي الوزارة السابعة عشر بعد المائة في تاريخ مصر. كُلف عصام شرف بتشكيل ال...

For the Congress of Deputies constituency, see Albacete (Congress of Deputies constituency). For the Senate constituency, see Albacete (Senate constituency). AlbaceteCortes of Castilla–La ManchaElectoral constituencyLocation of Albacete within Castilla–La ManchaProvinceAlbaceteAutonomous communityCastilla–La ManchaPopulation386,464 (2021)[1]Electorate308,216 (2023)Major settlementsAlbaceteCurrent constituencyCreated1983Seats9 (1983–1986)10 (1986–2014)6 (2014–2019)7 (2019�...

Artikel ini bukan mengenai Menoreh. Lihat pula: Menorah (Hanukkah) Menorah adalah kata bahasa Ibrani untuk Kandil atau Kaki Dian (disebut juga Kaki Pelita atau Pelita saja; bahasa Ibrani: מנורה - menôrâh. Dalam rangka pembangunan Kemah Suci Allah memerintahkan untuk membuat sebuah Menorah, yaitu Kandil atau Kaki Pelita, berhias terbuat dari emas (Keluaran 25:31). Dari batang tiang utama yang menyangga pegangan pelita, muncul 3 pasang cabang dengan arah berlawanan, yang pada ujung-ujung...

Ethiopian athlete Berihu AregawiAregawi at the 2023 World Athletics ChampionshipsPersonal informationNationalityEthiopianBorn (2001-02-28) 28 February 2001 (age 23)Tigray Region, EthiopiaSportCountryEthiopiaSportAthleticsEventLong-distance runningAchievements and titlesPersonal bests3000 m: 7:26.81 (Monaco 2022)5000 m: 12:40.45 (Lausanne 2023)10,000 m: 26:46.13 (Hengelo 2022)Road5 km: 12:49 WR (Barcelona 2021)10 km: 26:33 NR (Laredo 2023) Medal record Men's athle...

Central business district of Oakland, California This article uses bare URLs, which are uninformative and vulnerable to link rot. Please consider converting them to full citations to ensure the article remains verifiable and maintains a consistent citation style. Several templates and tools are available to assist in formatting, such as reFill (documentation) and Citation bot (documentation). (September 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Downtown Oakland from Lake Merritt Aeria...

Frances StarrTheatre Magazine, 1907LahirFrances Grant Starr(1886-06-06)6 Juni 1886Oneonta, New York, A.S.Meninggal11 Juni 1973(1973-06-11) (umur 87)New York City, A.S.MakamAlbany Rural Cemetery[1]PekerjaanAktrisTahun aktif1901–1955Suami/istriHaskell CoffinRobert G. DonaldsonEmil C. Wetten[2] Frances Grant Starr (6 Juni 1886 – 12 Juni 1973) adalah seorang aktris panggung, film dan televisi Amerika. Referensi ^ Van Tuyl lot, sec. 122, lot 11, Albany ...

Contaminación del agua debido a la producción lechera en el área de Wairarapa, en Nueva Zelanda (fotografía de 2003). La contaminación agrícola se refiere a los subproductos bióticos y abióticos de las prácticas agrícolas que resultan en la contaminación o degradación del medio ambiente y los ecosistemas circundantes, y que causan daños a los humanos y sus intereses económicos. La contaminación puede provenir de una variedad de fuentes, que van desde la contaminación del agua ...