Maurice Duruflé

| |||||||||||

Read other articles:

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Fourneyron. Valérie Fourneyron Valérie Fourneyron en 2013. Fonctions Députée française 4 juillet 2014 – 20 juin 2017(2 ans, 11 mois et 16 jours) Élection 17 juin 2012 Circonscription 1re de la Seine-Maritime Législature XIVe (Cinquième République) Groupe politique SRC (2014-2016)SER (2016-2017) Prédécesseur Pierre Léautey Successeur Damien Adam 20 juin 2007 – 21 juillet 2012 (5 ans, 1 mois et 1 jour) Élection 17...

Chemical compound TybamateClinical dataATC codenoneIdentifiers IUPAC name [2-(Carbamoyloxymethyl)-2-methylpentyl] N-butylcarbamate CAS Number4268-36-4 YPubChem CID20266ChemSpider19092 NUNII3875LLL8M8KEGGD06260 YCompTox Dashboard (EPA)DTXSID7023728 ECHA InfoCard100.022.050 Chemical and physical dataFormulaC13H26N2O4Molar mass274.361 g·mol−13D model (JSmol)Interactive image SMILES CCCCNC(=O)OCC(C)(CCC)COC(=O)N InChI InChI=1S/C13H26N2O4/c1-4-6-8-15-12(17)19-10-13(3,7-5-2)9...

American actress (born 1970) Lara Flynn BoyleBoyle at the 1990 Primetime Emmy AwardsBorn (1970-03-24) March 24, 1970 (age 54)Davenport, Iowa, U.S.OccupationActressYears active1986–presentSpouses John Patrick Dee III (m. 1996; div. 1998) Donald Ray Thomas II (m. 2006)RelativesCharles A. Boyle (grandfather) Lara Flynn Boyle (born March 24, 1970) is an American actress. She is known for playing...

StrømsgodsetBerkas:Strømsgodset IF logo.svgNama lengkapStrømsgodset ToppfotballJulukanGodsetBerdiri10 February 1907; 117 tahun lalu (10 February 1907)StadionMarienlyst Stadion(Kapasitas: 8,935)KetuaIvar StrømsjordetManager(s)Jørgen IsnesLigaEliteserien2023Eliteserien, 7 dari 16Situs webSitus web resmi klub Kostum kandang Kostum tandang Musim ini Strømsgodset Toppfotball adalah klub sepak bola profesional Norwegia yang berbasis di Gulskogen, Drammen, yang berkompetisi di Elites...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Amalgam (disambiguasi). Arquerite, amalgam alami antara perak dan raksa Amalgam adalah paduan antara raksa dengan logam lain. Amalgam bisa berwujud cairan, pasta lunak atau padat, tergantung pada proporsi raksa. Paduan ini dibentuk melalui ikatan logam,[1] dengan gaya tarik elektrostatis dari elektron konduksi yang bekerja untuk mengikat semua ion logam bermuatan positif menjadi struktur kisi kristal.[2] Hampir semua logam dapat membentuk amalgam den...

Bahasa Melayu PenesakBPS: 0053 4 باسو ڤنساقbaso Penesakbaso diri Dituturkan diIndonesiaWilayah Sumatera Selatan EtnisPenesakPenutur130.000 Rumpun bahasa Austronesia Melayu-Polinesia Diperdebatkan:Melayu-Sumbawa atau Kalimantan Utara Raya (?) Melayu-Chamik Melayik Musi Palembang–Dataran Rendah Bahasa Penesak Kode bahasaISO 639-3(kode pen telah digabungkan ke mui pada tahun 2007)[1]BPS (2010)0053 4QIDQ12953030Lokasi penuturanLokasi penuturan Bahasa PenesakPeta...

Gustavo Lopez Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Gustavo Fabián LópezTanggal lahir 28 April 1983 (umur 40)Tempat lahir Isidro Casanova, ArgentinaTinggi 1,80 m (5 ft 11 in)Posisi bermain GelandangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Arema IndonesiaNomor 8Karier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2003 Lanús 8 (0)2003 CA Los Andes 2004 Estudiantes de Mérida 2005 Huracán C.R. 2006 Barracas Central 2006-2007 Persela Lamongan 18 (4)2007 Alianza FC 2007-2009 Budućnost Podgorica 32 (3)2009-201...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Heart of America 200NASCAR Seri Truk Camping WorldTempatKansas SpeedwayLokasiKansas City, Kansas, Amerika SerikatPerusahaan sponsorAdventHealthLomba pertama2001Jarak tempuh250,5 mil (403,1 km)Jumlah putaran134[1]Tahap 1/2: 30 masing-masingTahap akhir: 74Nama sebelumnyaO'Reilly Auto Parts 250 (2001–2011)SFP 250 (2012–2014)Toyota Tundra 250 (2015–2017) 37 Kind Days 250 (2018)[2]Digital Ally 250 (2019)[3]Blue-Emu Maximum Pain Relief 200 (2020, ke-1)e.p.t. 200 (...

Un cerotto contraccettivo del marchio OrthoEvra Il cerotto contraccettivo o cerotto transdermico è un metodo contraccettivo rivolto alle donne, consistente in un cerotto adesivo che contiene un insieme di farmaci, da applicare sulla cute del corpo. Indice 1 Funzionamento 2 Farmacocinetica 3 Applicazione 4 Efficacia 5 Note 6 Voci correlate 7 Altri progetti 8 Collegamenti esterni Funzionamento Questo metodo contraccettivo non risente delle condizioni che alterano l'assorbimento gastrointestina...

French-born English painter Philip James de LoutherbourgPhilip James de Loutherbourg, self-portraitBornPhilippe Jacques de Loutherbourg(1740-10-31)31 October 1740Strasbourg, Alsace, FranceDied11 March 1812(1812-03-11) (aged 71)Chiswick, Middlesex, BritainNationalityBritishEducationCharles-André van Loo Francesco Giuseppe CasanovaKnown forPaintingNotable workLord Howe's action, or the Glorious First of June Coalbrookdale by NightMovementHistory painting Military art Philip James de ...

拉吉夫·甘地राजीव गांधीRajiv Gandhi1987年10月21日,拉吉夫·甘地在阿姆斯特丹斯希普霍尔机场 第6任印度总理任期1984年10月31日—1989年12月2日总统吉亞尼·宰爾·辛格拉马斯瓦米·文卡塔拉曼前任英迪拉·甘地继任維什瓦納特·普拉塔普·辛格印度對外事務部部長任期1987年7月25日—1988年6月25日前任Narayan Dutt Tiwari(英语:Narayan Dutt Tiwari)继任納拉辛哈·拉奥任期1984年10�...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会波兰代表團波兰国旗IOC編碼POLNOC波蘭奧林匹克委員會網站olimpijski.pl(英文)(波兰文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員206參賽項目24个大项旗手开幕式:帕维尔·科热尼奥夫斯基(游泳)和马娅·沃什乔夫斯卡(自行车)[1]闭幕式:卡罗利娜·纳亚(皮划艇)&#...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会波兰代表團波兰国旗IOC編碼POLNOC波蘭奧林匹克委員會網站olimpijski.pl(英文)(波兰文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員206參賽項目24个大项旗手开幕式:帕维尔·科热尼奥夫斯基(游泳)和马娅·沃什乔夫斯卡(自行车)[1]闭幕式:卡罗利娜·纳亚(皮划艇)&#...

Military overthrow of President Bah N'daw 2021 Malian coup d'étatPart of the Mali War and the Coup BeltDate24 May 2021 (2021-05-24)LocationMaliResult Coup d'état successful Resignation of interim president Bah Ndaw and prime minister Moctar Ouane Vice President Assimi Goïta named interim President by Constitutional Court of Mali Mali suspended from ECOWAS, La Francophonie and the African Union[1] Choguel Kokalla Maïga named interim prime minister[2] France s...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (مارس 2016) ميناء عبد الله الإحداثيات 29°01′01″N 48°09′37″E / 29.0169°N 48.1603°E / 29.0169; 48.1603 تقسيم إداري البلد ا...

Priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Dardania Montfoort's rendering of the Hellespontine Sibyl Statue in Scalzi, Venice The Hellespontine Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Dardania. The Sibyl is sometimes referred to as the Trojan Sibyl. The word Sibyl comes (via Latin) from the Ancient Greek word sibylla, meaning prophetess or oracle. The Hellespontine Sibyl was known, particularly in the late Roman Imperial period and the early Middle Ages, for a c...

Election for Lieutenant Governor of Minnesota Minnesota lieutenant gubernatorial election, 1918 ← 1916 November 5, 1918 1920 → Nominee Thomas Frankson Charles H. Helweg George D. Haggard Party Republican Democratic National Popular vote 198,878 97,350 44,336 Percentage 58.4% 28.58% 13.02% Lieutenant Governor before election Thomas Frankson Republican Elected Lieutenant Governor Thomas Frankson Republican Elections in Minnesota General elections 2006 2008 2010...

EyjafjallajökullGuðnasteinn HámundurGígjökull, gletser luar Ejjafjallajökull terbesar yang tertutup abu vulkanisTitik tertinggiKetinggianMountain: 1.651 m (5.417 ft) Glacier: 1.666 m (5.466 ft)[1]Koordinat63°37′12″N 19°36′48″W / 63.62000°N 19.61333°W / 63.62000; -19.61333 [2]GeografiEyjafjallajökullIslandiaLetakSuðurland, IslandiaPegununganN/AGeologiJenis gunungGunung berapi kerucutBusur/sabuk vulkanikEast V...

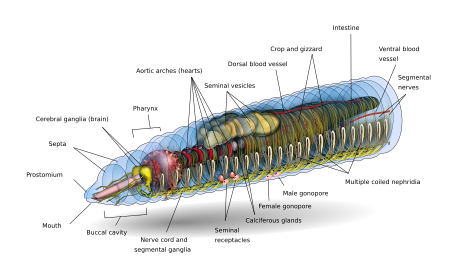

Terrestrial invertebrate, order Opisthopora EarthwormTemporal range: 209–0 Ma[1] PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N An unidentified earthworm species with a well-developed clitellum Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Annelida Clade: Pleistoannelida Clade: Sedentaria Class: Clitellata Order: Opisthopora Suborder: Lumbricina An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for...