Matilda, Abbess of Quedlinburg

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Zambian football club Football clubNchanga Rangers fcFull nameNchanga Rangers Football ClubCapacity15,000ChairmanYoram KapaiManagerPatrick NkhataLeagueMTN/FAZ Super Division201919th Home colours Away colours Nchanga Rangers is a Zambian football club based in Chingola that plays in the MTN/FAZ Super Division. They play their home games at Nchanga Stadium in Chingola. The club is sponsored by Konkola Copper Mines.[1] Achievements Zambian Premier League: 2 1980, 1998 Independence Cup: 1...

† Человек прямоходящий Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:Синапсиды�...

Team sport originating in Ireland; related to polo but played on bicycles Not to be confused with Cycle ball. Cycle poloBike polo match in BudapestHighest governing bodyInternational Bicycle Polo Federation, North American Bike Polo Association, European Hardcourt Bike Polo AssociationFirst playedOctober 1891 - County Wicklow, Ireland. (Rathclaren Rovers V Ohne Hast Cycling Club)CharacteristicsTeam membersFive or ThreeTypeTeam sportEquipmentBicycle, Mallet, BallPresenceOlympicLondon, 190...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Мотыль (значения). Для термина «Мотыли» см. также другие значения. Личинка комара (красного цвета) Мотыль в коробке Моты́ль — распространённое название червевидных красных личинок комаров семейства Chironomidae, достигающих ...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с такой фамилией, см. Чичваркин; Чичваркин, Евгений. Евгений Чичваркин В 2019 году Дата рождения 10 сентября 1974(1974-09-10) (49 лет) Место рождения Ленинград, РСФСР, СССР Гражданство Россия → Великобритания Род деятельности предпринимат...

British Labour Co-op politician Stephen TwiggOfficial portrait, 20178th Secretary-General of the Commonwealth Parliamentary AssociationIncumbentAssumed office August 2020Preceded byKarimulla Akbar KhanChair of the International Development CommitteeIn office19 May 2015 – 6 November 2019Preceded byMalcolm BruceSucceeded bySarah ChampionShadow Secretary of State for EducationIn office7 October 2011 – 7 October 2013LeaderEd MilibandPreceded byAndy BurnhamSucceeded byTri...

Figur einer Schnitterin von Jakob Wilhelm Fehrle am Dorfbrunnen im Leonberger Stadtteil Eltingen in Baden-Württemberg, 1937 Katharina Kepler gewidmet Katharina Kepler (* 8. November 1547 in Eltingen bei Leonberg; † 13. April 1622 in Roßwälden)[1] war die Mutter des kaiserlichen Astronomen Johannes Kepler. Sie wurde 1615 während einer Hexenverfolgung in einem der bekanntesten württembergischen Hexenprozesse angeklagt und nicht zuletzt durch die Bemühungen ihres bekannten Sohnes...

Feature of computer systems This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (May 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Direct memory access (DMA) is a feature of computer systems that allows certain hardware subsystems to access main system memory independently of the central processing unit (CPU).[1] Without DMA, when the CPU is using prog...

Daftar pemenang Miss Grand InternationalLogo Miss Grand InternationalTanggal pendirian2013Kantor pusatBangkokLokasi ThailandBahasa resmi InggrisPresidenNawat ItsaragrisilSitus webSitus web resmi Berikut ini adalah daftar pemenang pada kontes kecantikan Miss Grand International: Daftar Pemenang Tahun Negara asal Miss Grand International Gelar nasional Lokasi acara Jumlah peserta 2024 TBA TBA TBA Yangoon, Myanmar TBA 2023 Peru Luciana Fuster Miss Grand Peru 2023 Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam ...

Hawthorn Football Club2023 seasonPresidentJeff Kennett (until 13 December 2022)Andrew Gowers (from 13 December 2022)CoachSam MitchellCaptain(s)James SicilyHome groundMelbourne Cricket Ground University of Tasmania StadiumRecord7–16 (16th)Best and FairestWill DayLeading goalkickerLuke Breust (47) ← 2022 2024 → The 2023 Hawthorn Football Club season was the club's 99th season in the Australian Football League and 122nd overall, the 24th season playing home games at the Melbourne ...

US National Scenic Trail For the film, see Arizona Trail (film). Arizona TrailKentucky Camp, along the Arizona Trail in the Santa Rita Mountains.Length800 mi (1,300 km)LocationArizona, United StatesDesignationNational Scenic TrailTrailheadsCoronado National MemorialArizona–Utah borderUseHiking, horseback riding, mountain biking, cross-country skiingHighest pointSan Francisco Peaks (This point is on a proposed section of the trail), 9,600 ft (2,900 m)Lowest pointGila Rive...

1948–1960 conflict in British Malaya Malayan EmergencyDarurat Malaya馬來亞緊急狀態மலாயா அவசரகாலம்Part of the decolonization of Asia and Cold War in Asia Clockwise from top left: Australian Avro Lincoln bomber dropping 500lb bombs Communist leader Lee Meng in 1952 RAF staff loads bombs to be used against communist rebels King's African Rifles search abandoned hut Civilians forcibly evicted from their land by the British as part of the Briggs' Plan Date16 Ju...

Subdivision of Indian state of Karnataka This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Ballari district – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (Ja...

Thames Barrier Park (Mar 2007) Lister Gardens (December 2021) The London Borough of Newham, in spite of being one of the more crowded areas of London, has over 20 parks within its boundaries, as well as smaller recreation grounds. The larger parks in the Borough include: Beckton District Park North Beckton District Park South Central Park, East Ham East Ham Nature Reserve King George V Park, Custom House Memorial Recreation Ground, one-time home of West Ham United and its predecessor Thames ...

American businessman (born 1946) For the Pennsylvania politician, see James C. Roberts (politician). James Cleveland Roberts (born August 9, 1946) is the President of the American Studies Center, a non-profit foundation founded in 1978 and currently headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. James C. Roberts In 1985, Roberts founded Radio America, a news/talk network that now has more than 700 affiliates nationwide and more than 7 million listeners. In 1995, Roberts founded the American Veterans C...

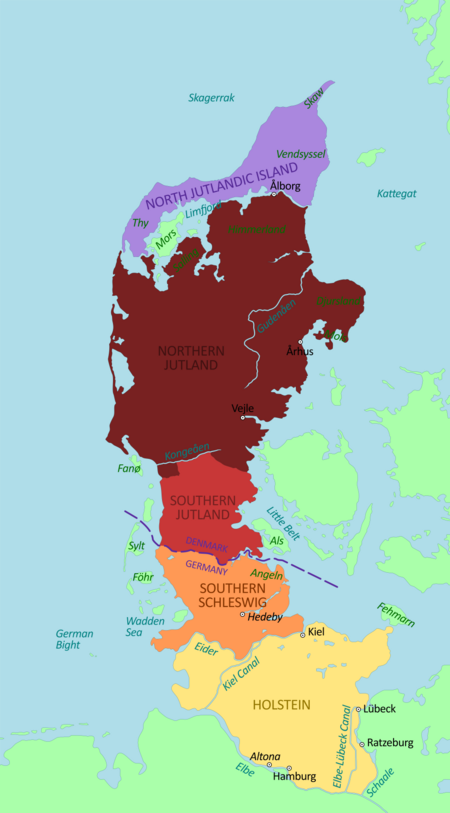

Semenanjung Jutland, tanah air Jute. Jute adalah sebuah suku bangsa Jermanik. Menurut Bede,[1] Jute adalah salah satu dari tiga suku Jermanik paling berpengaruh di masa mereka pada Zaman Besi Nordik,[2][3] dua lainnya adalah Saxon dan Angle.[4][5] Jute diyakini berasal dari Semenanjung Jutland dan bagian dari pantai Frisia Utara. Pada masa sekarang, Semenanjung Jutland terdiri dari daratan utama Denmark dan Schleswig Selatan di Jerman. Frisia Utara juga...

Chronologies Données clés 1234 1235 1236 1237 1238 1239 1240Décennies :1200 1210 1220 1230 1240 1250 1260Siècles :XIe XIIe XIIIe XIVe XVeMillénaires :-Ier Ier IIe IIIe Chronologies thématiques Religion (,) et * Croisades Science () et Santé et médecine Terrorisme Calendriers Romain Chinois Grégorien Julien Hébraïque Hindou Hégirien Persan Républicain modifier Années de la santé et de la médecine ...

Marcello Sparzo (Urbino, XVI secolo – Urbino, 1616[1][2]) è stato uno scultore italiano, noto in particolare come maestro stuccatore. Considerato dai coevi uno dei massimi plasticatori del periodo,[3][4][5][6][7] fu tra i primi utilizzatori dello stucco nelle opere monumentali colossali,[5][8][9] mostrando un originale linguaggio stilistico e una raffinata capacità esecutiva.[10] Operò in particolare ...

Department of the University of São Paulo Reopening of the entrance on the Matão Street to the Institute of Physics. The Institute of Physics of the University of São Paulo (Portuguese: Instituto de Física da Universidade de São Paulo), also known as IFUSP, is the largest and oldest physics research and teaching institution in Brazil. It is a public higher education unit located on the Armando de Salles Oliveira University City, in São Paulo. Created in 1970, it is the result of the com...

Solving Rubik's Cubes or other twisty puzzles with speed This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Speedcubing – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (...