Luteoma

| |||||||

Read other articles:

Ersilio ToniniKardinal, Uskup Agung Emeritus Ravenna-CerviaKeuskupan agungRavenna-CerviaTakhtaRavenna-CerviaPenunjukan22 November 1975Masa jabatan berakhir27 Oktober 1990PendahuluSalvatore BaldassarriPenerusLuigi AmaducciJabatan lainKardinal-Imam Santissimo Redentore a ValmelainaImamatTahbisan imam18 April 1937Tahbisan uskup2 Juni 1969oleh Umberto MalchiodiPelantikan kardinal26 November 1994PeringkatCardinal-PriestInformasi pribadiLahir(1914-07-20)20 Juli 1914Centovera di San Giorgio Pia...

Village and area in Hong Kong Hong Kong National Geopark sign in Lai Chi Chong. Lai Chi ChongTraditional Chinese荔枝莊Simplified Chinese荔枝庄TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinLìzhī ZhuāngYue: CantoneseJyutpinglai6 zi1 zong1 Residential houses and Hui (許) Ancestral Hall in Lai Chi Chong. Mangroves at Lai Chi Chong. Lai Chi Chong ferry pier. Lai Chi Chong (Chinese: 荔枝莊) is a village and an area of Hong Kong, located on the southeastern shore of Tolo Channel, ...

Motion problem in classical mechanics This article is about the two-body problem in classical mechanics. For the relativistic version, see Two-body problem in general relativity. For the career management problem of working couples, see Two-body problem (career). Left: Two bodies with similar mass orbiting a common barycenter external to both bodies, with elliptic orbits—typical of binary stars . Right: Two bodies with a slight difference in mass orbiting a common barycenter. The sizes, and...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Izumi, Kagoshima – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) City in Kyushu, JapanIzumi 出水市City FlagEmblemLocation of Izumi in Kagoshima PrefectureIzumiLocation in JapanCoordinates: 3...

Pembangunan Bahtera Nuh karya Jacopo Bassano menggambarkan seluruh delapan orang yang dikatakan berada di bahtera, termasuk empat istri. Istri-istri di Bahtera Nuh adalah bagian dari keluarga yang selamat dari air bah. Mereka adalah istri Nuh, dan istri dari masing-masing tiga putranya. Meskipun Alkitab hanya menyebut keberadaan wanita tersebut, sumber di luar Alkitab menyebut penjelasan lain tentang mereka dan nama-nama mereka. Taurat Dalam Kejadian 6:18, Allah berkata kepada Nuh, Tetapi den...

Statue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lincoln MonumentThe monument in 202339°58′10.56″N 75°11′4.02″W / 39.9696000°N 75.1844500°W / 39.9696000; -75.1844500LocationKelly Drive & Sedgley Drive,Fairmount Park, PhiladelphiaDesignerRandolph RogersTypeStatueMaterialSculpture: bronzeBase: granite & bronzeLength17 ft (5.2 m)[1]Width15 ft (4.6 m)[1]HeightOverall: 32 ft (9.8 m)[1]Sculpture: 8.67 ft (2.6...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Пт�...

American basketball coach and player (born 1951) George KarlKarl coaching the Denver Nuggets in 2011Personal informationBorn (1951-05-12) May 12, 1951 (age 72)Penn Hills, Pennsylvania, U.S.Listed height6 ft 2 in (1.88 m)Listed weight185 lb (84 kg)Career informationHigh schoolPenn Hills(Penn Hills, Pennsylvania)CollegeNorth Carolina (1970–1973)NBA draft1973: 4th round, 66th overall pickSelected by the New York KnicksPlaying career1973–1978PositionPoint guardNu...

Sceaux 行政国 フランス地域圏 (Région) イル=ド=フランス地域圏県 (département) オー=ド=セーヌ県郡 (arrondissement) アントニー郡小郡 (canton) 小郡庁所在地INSEEコード 92071郵便番号 92330市長(任期) フィリップ・ローラン(2008年-2014年)自治体間連合 (fr) メトロポール・デュ・グラン・パリ人口動態人口 19,679人(2007年)人口密度 5466人/km2住民の呼称 Scéens地理座標 北緯48度4...

German politician Markus BuchheitMEPMember of the European Parliamentfor GermanyIncumbentAssumed office 2 July 2019[1][2] Personal detailsNationalityGermanPolitical partyAlternative for Germany (2016-) Christian Social Union in Bavaria (before 2016) Markus Buchheit (born August 11, 1983 in Zweibrücken) is a German politician who is serving as an Alternative for Germany Member of the European Parliament.[3] Buchheit grew up in Pollenfeld and attended school in...

Sporting event delegationChina at the2012 Summer ParalympicsIPC codeCHNNPCChina Administration of Sports for Persons with DisabilitiesWebsitewww.caspd.org.cnin LondonCompetitors282 in 15 sportsFlag bearer Zhang LixinMedalsRanked 1st Gold 95 Silver 71 Bronze 65 Total 231 Summer Paralympics appearances (overview)19841988199219962000200420082012201620202024 China competed at the 2012 Summer Paralympics in London, United Kingdom, from 29 August to 9 September 2012.[1] Medalists Gold ...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Januari 2023. Robertus Tony SuwandiTony Suwandi sedang memimpin latihan konser Wacana Bhakti Symphony OrchestraLahir18 April 1943 (umur 81) Jakarta, Masa Pendudukan JepangMeninggal7 Juli 2013(2013-07-07) (umur 70) Jakarta, IndonesiaKebangsaanIndonesiaPeker...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目需要編修,以確保文法、用詞、语气、格式、標點等使用恰当。 (2013年8月6日)請按照校對指引,幫助编辑這個條目。(幫助、討論) 此條目剧情、虛構用語或人物介紹过长过细,需清理无关故事主轴的细节、用語和角色介紹。 (2020年10月6日)劇情、用語和人物介紹都只是用於了解故事主軸,輔助�...

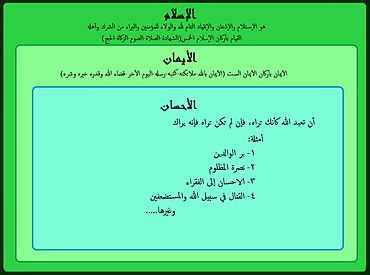

هذه المقالة بحاجة لصندوق معلومات. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة صندوق معلومات مخصص إليها. يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (يناير 2022) هذه الم...

Ritratto di Francis Bacon Francis Bacon, latinizzato in Franciscus Baco(nus) e italianizzato in Francesco Bacone (Londra, 22 gennaio 1561 – Londra, 9 aprile 1626), è stato un filosofo, politico, giurista e saggista inglese vissuto alla corte inglese. Fu Procuratore generale e Lord cancelliere sotto il regno di Giacomo I Stuart. Formatosi con studi in legge e giurisprudenza, divenne uno strenuo difensore della rivoluzione scientifica, su cui le sue opere ebbero una importante e duratura inf...

French colonial buildings in Kampot, Cambodia Place in Kampot, CambodiaBokor Hill Station ស្ថានីយភ្នំបូកគោStation d'altitude de BokorThe abandoned Bokor Palace Hotel (2007)Bokor Hill StationLocation of the Town of Phnom BokorCoordinates: 10°37′49.47″N 104°1′2.16″E / 10.6304083°N 104.0172667°E / 10.6304083; 104.0172667Country CambodiaProvinceKampotMunicipalityKampotBuilt1921Elevation1,048 m (3,438 ft)Population&...

一中同表,是台灣处理海峡两岸关系问题的一种主張,認為中华人民共和国與中華民國皆是“整個中國”的一部份,二者因為兩岸現狀,在各自领域有完整的管辖权,互不隶属,同时主張,二者合作便可以搁置对“整个中國”的主权的争议,共同承認雙方皆是中國的一部份,在此基礎上走向終極統一。最早是在2004年由台灣大學政治学教授張亞中所提出,希望兩岸由一中各表�...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع إيمان (توضيح). الإيمان في الإسلاممعلومات عامةصنف فرعي من إيمان جزء من عقيدة إسلامية الاستعمال العمل الصالح في الإسلام العمل في الإسلام جانب من جوانب الغيب في الإسلامسبيل اللهالصراط المستقيم الدِّين الإسلامصوفية سُمِّي باسم أمن اللغة الرسمية العر�...

2015 single by The Game and SkrillexEl ChapoSingle by The Game and Skrillexfrom the album The Documentary 2.5 ReleasedOctober 9, 2015 (2015-10-09)GenreHip hoptrapLength3:40LabelBlood MoneyeOneSongwriter(s)Jayceon TaylorSonny MooreShondrae CrawfordProducer(s)Mr. BangladeshSkrillexNastradomasThe Game singles chronology 100 (2015) El Chapo (2015) All Eyez (2016) Skrillex singles chronology Where Are Ü Now(2015) El Chapo(2015) To Ü(2015) El Chapo is the second single by A...