Local anesthesia

| |||||

Read other articles:

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada April 2016. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Telecommunications & Information Working Group (APEC TEL) adalah asosiasi kerjasama ekonomi tingkat Asia Pasifik di bidang telekomunikasi dan informatika.[1] APEC TEL juga merupakan bagian dari grup kerja Asi...

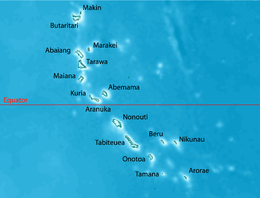

AbemamaGeografia fisicaLocalizzazioneOceano Pacifico Coordinate0°23′15.13″N 173°46′42.41″E / 0.387536°N 173.778447°E0.387536; 173.778447Coordinate: 0°23′15.13″N 173°46′42.41″E / 0.387536°N 173.778447°E0.387536; 173.778447 ArcipelagoIsole Gilbert Superficie16 km² Geografia politicaStato Kiribati Centro principaleKariatebike DemografiaAbitanti3.257 (2020) Cartografia Abemama voci di isole delle Kiribati presenti su Wikipedia Abemama ...

FaworkiFaworkiNama lainFavorki, Angel wings, BugneTempat asalPolandia, ItaliaBahan utamaAdonan, gula bubukEnergi makanan(per porsi )558 per 100 g kkalSunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Media: Faworki Faworki (juga disebut favorki) adalah sebuah kue tradisional yang renyah dan manis yang terbuat dari adonan yang telah dibentuk menjadi seperti pita-tipis yang digulung, benar-benar digoreng dan diberi taburan gula. Awalnya dikenal sebagai kuline...

Wikimedia Commons memiliki media mengenai Hedychium coronarium. Gandasuli Hedychium coronarium Bunga gandasuli Status konservasi Aman (NatureServe) Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Viridiplantae Superdivisi: Tracheophyta Divisi: Angiospermophyta Kelas: Liliopsida Superordo: Commelinids Ordo: Zingiberales Famili: Zingiberaceae Genus: Hedychium Spesies: H. coronarium Nama binomial Hedychium coronariumJ. Koenig Sinonim Amomum filiforme Hunter ex Ridl. Gandasulium coronarium (J.Koenig) Kun...

Bashung pada 2007 Alain Bashung (bahasa Prancis: [alɛ̃ baʃuŋ]; nama lahir Alain Claude Baschung, 1 Desember 1947 – 14 Maret 2009) merupakan penyanyi Prancis, penulis lagu dan pemeran. Dia berjasa dengan menghidupkan kembali chanson Prancis di saat kekacauan musik Prancis,[1] ia sering dianggap di negara asalnya sebagai musisi rock Prancis terpenting setelah Serge Gainsbourg.[2] Dia mulai tenar pada awal 1980-an dengan lagu-lagu hit seperti Gaby oh Gaby dan Vertige d...

Strada statale 113Settentrionale SiculaLocalizzazioneStato Italia Regioni Sicilia Province Messina Palermo Trapani DatiClassificazioneStrada statale InizioMessina FineTrapani Lunghezza377,00[1] km Provvedimento di istituzioneLegge 17 maggio 1928, n. 1094 GestoreANAS Manuale La strada statale 113 Settentrionale Sicula (SS 113) è una strada statale italiana che si snoda lungo la costa settentrionale della Sicilia, andando da Messina a Trapani, passando per Palermo. ...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Porcelaine (homonymie). La porcelaine est caractérisée par sa finesse et sa transparence après cuisson. La porcelaine est une céramique fine et translucide qui, si elle est produite à partir du kaolin par cuisson à plus de 1 200 °C, prend le nom plus précis de porcelaine dure. Elle est majoritairement utilisée dans les arts de la table. Les techniques de fabrication de la porcelaine atteignent leur perfection en Chine au XIIe siècle,...

Galaxy in the constellation Capricornus NGC 6907NGC 6907 by GALEXObservation data (J2000 epoch)ConstellationCapricornusRight ascension20h 25m 06.6s[1]Declination−24° 48′ 33″[1]Redshift0.010614 ± 0.000013[1]Heliocentric radial velocity3,182 ± 4 km/s[1]Distance118 Mly (36.3 Mpc)[2]Apparent magnitude (V)11.1[3]CharacteristicsTypeSB(s)bc[1]Apparent size (V)3′.3 × 2′.7[1]Notable featuresLu...

Peta lokasi Kabupaten Sekadau Berikut adalah daftar kecamatan dan kelurahan di Kabupaten Sekadau, Provinsi Kalimantan Barat, Indonesia. Kabupaten Sekadau terdiri dari 7 kecamatan dan 87 desa. Pada tahun 2017, jumlah penduduknya mencapai 208.791 jiwa dengan luas wilayah 5.444,20 km² dan sebaran penduduk 38 jiwa/km².[1][2] Daftar kecamatan dan kelurahan di Kabupaten Sekadau, adalah sebagai berikut: Kode Kemendagri Kecamatan Jumlah Desa Daftar Desa 61.09.07 Belitang 7 Belitang ...

1999 European Parliament election in Spain ← 1994 13 June 1999 2004 → ← outgoing memberselected members →All 64 Spanish seats in the European ParliamentOpinion pollsRegistered33,840,432 7.2%Turnout21,334,948 (63.0%)3.9 pp First party Second party Third party Leader Loyola de Palacio Rosa Díez Alonso Puerta Party PP PSOE–p IU–EUiA Alliance EPP (EPP–ED) PES GUE/NGL Leader since 22 April 1999 22 March 1999 2 March 1994 L...

هذه المقالة بحاجة لصندوق معلومات. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة صندوق معلومات مخصص إليها. دَيْوِيِ देवी تعني بالسنسكريتية الإلهة نفس معنى شاكتي الجانب الأنثوي للألوهية في الهندوسية التي تؤمن أنه بدون الجانب الأنثوي تبقى الآلهة المذكرة عاجزة.[1][2][3] ...

هذه المقالة بحاجة لصندوق معلومات. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة صندوق معلومات مخصص إليها. فريق برشلونة عام 1903. نادي برشلونة (بالكتالونية: Futbol Club Barcelona)، هو نادي رياضي إسباني. تأسس في نوفمبر من 1899 على يد مجموعة من اللاعبين من أربع جنسيات سويسرية وإنجليزية وألمانية وإ�...

أبو طالب المشكاني معلومات شخصية تاريخ الوفاة سنة 858 مواطنة الدولة العباسية الحياة العملية تعلم لدى أحمد بن حنبل المهنة فقيه اللغات العربية تعديل مصدري - تعديل أبو طالب أحمد بن حُمَيْد المُشْكانِيُّ (ت. 244 هـ)، صاحب أحمد بن حنبل والمتخصص في ذلك،[1] روى...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (نوفمبر 2019) الدوري الجورجي الممتاز 1991–92 تفاصيل الموسم الدوري الجورجي الممتاز النسخة 3 البلد جورجيا التاري...

1943 film by A. Edward Sutherland DixieTheatrical release posterDirected byA. Edward SutherlandWritten by Karl Tunberg Darrell Ware Claude Binyon (adaptation) Story byWilliam RankinProduced byPaul JonesStarring Bing Crosby Dorothy Lamour CinematographyWilliam C. MellorEdited byWilliam SheaMusic by Jimmy Van Heusen Johnny Burke ProductioncompanyParamount PicturesDistributed byParamount PicturesRelease date June 23, 1943 (1943-06-23) (New York City) Running time89 minutesCoun...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (septembre 2021). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ...

Dalam nama Korean ini, nama keluarganya adalah Lee. Lee Tae-gonLahir27 November 1977 (umur 46)Daejeon, Korea SelatanPekerjaanAktorTahun aktif2005–sekarangNama KoreaHangul이태곤 Hanja李太坤 Alih AksaraI Tae-gonMcCune–ReischauerYi Taekon Lee Tae-gon (Korea: 이태곤; lahir 27 November 1977) adalah aktor asal Korea Selatan. Kehidupan pribadi Lee menempuh pendidikan di Universitas Kyonggi, dimana ia mempelajari Pendidikan Fisik, jurusan renang, dia adalah instruktur renang ya...

American comic book artist (1931–1987) For the creator of Clifford, the Big Red Dog, see Norman Bridwell. E. Nelson BridwellBridwell in 1974BornEdward Nelson Bridwell(1931-09-22)September 22, 1931Sapulpa, Oklahoma, U.S.DiedJanuary 23, 1987(1987-01-23) (aged 55)Kings County, New York, U.S.Area(s)Writer, editorNotable worksThe Inferior FiveAwardsBill Finger Award Edward Nelson Bridwell (September 22, 1931 – January 23, 1987) was an American writer for Mad magazine (writing the now-famo...

«Местничество. Строптивый боярин, не желая занять дальнего от царя места за столом, опускается со скамьи на пол». Кадр из фильма «Трёхсотлетие царствования дома Романовых». Ме́стничество — система распределения должностей в зависимости от знатности рода, существова�...

西暦120年の属州ガリア・アクィタニア ガリア・アクィタニア(ラテン語: Gallia Aquitania ガッリア・アクィタニア)は、ローマ帝国の属州のひとつ。かつてのアクィタニア地方であり、現在のフランス南西部アキテーヌ地方に該当する。東方にガリア・ルグドゥネンシス、南方にガリア・ナルボネンシス、西方にヒスパニア・タッラコネンシスの各属州と接していた。 �...