Leah Song

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Academic journalThe American Journal of GastroenterologyDisciplineGastroenterologyLanguageEnglishEdited byJasmohan Bajaj, MD, MS, FACG & Millie Long, MD, MPH, FACGPublication detailsFormer name(s)Review of GastroenterologyHistory1934–presentPublisherLippincott Williams & Wilkins (United States)FrequencyMonthlyImpact factor12.045 (2021)Standard abbreviationsISO 4 (alt) · Bluebook (alt1 · alt2)NLM (alt) · MathSciNet (alt )ISO 4Am. J....

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Schmidt. Mads Würtz SchmidtMads Würtz Schmidt en 2017InformationsNaissance 31 mars 1994 (30 ans)RandersNationalité danoiseÉquipe actuelle Israel-Premier TechDistinction Cycliste danois de l'année (2015)Équipe non-UCI 2002-2010Randers CykleklubÉquipes UCI 2011Team Herning CK Junior2012Blue Water Junior2013Cult Energy2014Cult Energy Vital Water2015ColoQuick2016-7.2016Trefor7.2016-2016Virtu Pro-Veloconcept2017-2019Katusha-Alpecin2020-2021Israel Star...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Лиссабонский договор (значения). Не следует путать с Лиссабонским протоколом. Лиссабонский договорTreaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community Тип договора Поправки к предыдущим договорам Дата подготовки 7-8 �...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

この項目には、一部のコンピュータや閲覧ソフトで表示できない文字が含まれています(詳細)。 数字の大字(だいじ)は、漢数字の一種。通常用いる単純な字形の漢数字(小字)の代わりに同じ音の別の漢字を用いるものである。 概要 壱万円日本銀行券(「壱」が大字) 弐千円日本銀行券(「弐」が大字) 漢数字には「一」「二」「三」と続く小字と、「壱」「�...

内華達州 美國联邦州State of Nevada 州旗州徽綽號:產銀之州、起戰之州地图中高亮部分为内華達州坐标:35°N-42°N, 114°W-120°W国家 美國建州前內華達领地加入聯邦1864年10月31日(第36个加入联邦)首府卡森城最大城市拉斯维加斯政府 • 州长(英语:List of Governors of {{{Name}}}]]) • 副州长(英语:List of lieutenant governors of {{{Name}}}]])喬·隆巴爾多(R斯塔...

Ini adalah nama Papua, (Marind), marganya adalah Cawor Ricky Cawor Ricky Cawor di PON 2021 Papua.Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Ricky Ricardo Cristian CaworTanggal lahir 26 Januari 1998 (umur 26)Tempat lahir Merauke, IndonesiaTinggi 168 cm (5 ft 6 in)Posisi bermain PenyerangInformasi klubKlub saat ini PSS SlemanNomor 11Karier junior2013 Gelora Putra FC2021 PON PapuaKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2017–2018 Persimer Merauke 4 (0)2018 Persemi Mimika 10 (8)2021–2022 Pe...

Municipality in Neuchâtel, SwitzerlandCressierMunicipalityCressier village Coat of armsLocation of Cressier CressierShow map of SwitzerlandCressierShow map of Canton of NeuchâtelCoordinates: 47°3′N 7°2′E / 47.050°N 7.033°E / 47.050; 7.033CountrySwitzerlandCantonNeuchâtelArea[1] • Total8.55 km2 (3.30 sq mi)Elevation436 m (1,430 ft)Population (31 December 2018)[2] • Total1,886 • ...

نوكيا 8850معلومات عامةالنوع هاتف محمول الصانع نوكيا تعديل - تعديل مصدري - تعديل ويكي بيانات نوكيا 8850 هو أحد أجهزة نوكيا، شركة الهواتف والتقنية النقالة.[1] يأتي هذا الجهاز مع شاشة نوعها 84 * 48 ذو لون واحد (مونوكروم). تم إصدار هذا الجهاز في 1999. أما بالنسبة لوضعية إنتاجه الحالية �...

Irish software development company Demonware, Inc.Company typeSubsidiaryIndustryVideo gamesFounded2003; 21 years ago (2003)FounderDylan Collins and Sean BlanchfieldHeadquartersDublin, IrelandNumber of locations4 (2024)ProductsMiddlewareNumber of employees177ParentActivision (2007–present)Websitewww.demonware.net Demonware, Inc. is an Irish software development company and a subsidiary of Activision, a video game division of Activision Blizzard. Demonware's products en...

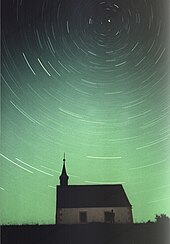

Foto Polaris long exposure (45 menit) dan bintang-bintang yang bertetangga, diambil di Ehrenbürg (Franconia), 2001. Bintang kutub adalah sebuah bintang, yang terang, sejajar dengan sumbu rotasi objek astronomi. Saat ini, bintang kutub utara Bumi adalah Polaris (Alpha Ursae Minoris), bintang magnitudo 2 yang kira-kira sejajar dengan sumbu utara, dan bintang yang paling terang yang ada di navigasi selestial dan Polaris Australis (Sigma Octantis), bintang yang jauh lebih redup. Beberapa ribu ta...

American tenor saxophonist Ron HollowayTenor saxophonist Ron Holloway during a tour of RussiaBackground informationBirth nameRonald Edward HollowayBorn (1953-08-24) August 24, 1953 (age 70)Washington, D.C., U.S.GenresJazz, R&B, blues, funk, rockOccupation(s)MusicianInstrument(s)Tenor saxophoneYears active1966–presentLabelsFantasy/MilestoneWebsitetheronhollowayband.comMusical artist Ronald Edward Holloway (born August 24, 1953) is an American tenor saxophonist. He is listed in the B...

Railway station in Surrey, England AshteadAshtead railway stationGeneral informationLocationAshtead, District of Mole ValleyEnglandGrid referenceTQ180589Managed bySouthernPlatforms2Other informationStation codeAHDClassificationDfT category EHistoryOpened1 February 1859Passengers2018/19 1.308 million2019/20 1.273 million2020/21 0.261 million2021/22 0.697 million2022/23 0.847 million NotesPassenger statistics from the Office of Rail and Road Ashtead railway station is in Ashtead, Surrey, Englan...

Railway station in Israel Ra'anana South railway stationתחנת הרכבת רעננה דרוםIsrael RailwaysThe underground platformsGeneral informationLocationRa'anana,IsraelCoordinates32°10′22″N 34°53′15″E / 32.17278°N 34.88750°E / 32.17278; 34.88750Line(s)Sharon RailwayPlatforms2Tracks2ConstructionParkingNoHistoryOpened3 July 2018; 5 years ago (2018-07-03)Electrified25 December 2021; 2 years ago (2021-12-25)Passenger...

Disambiguazione – Se stai cercando l'omonima valle, vedi Valsavarenche (valle). Valsavarenchecomune(IT) Comune di Valsavarenche(FR) Commune de Valsavarenche Valsavarenche – VedutaVista del comune nell'omonima valle LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regione Valle d'Aosta ProvinciaNon presente AmministrazioneCapoluogoDégioz SindacoTamara Lanaro (commissario prefettizio) dal 15-5-2022 Lingue ufficialiFrancese, italiano TerritorioCoordinatedel capoluogo45°35′31.92″N 7°12...

Questa voce sugli argomenti artisti marziali francesi e berberi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Larbi BenboudaoudNazionalità Francia Altezza170 cm Judo Categoria66 kg Palmarès Giochi olimpici ArgentoSydney 2000 Mondiali OroBirmingham 1999 ArgentoOsaka 2003 Europei OroOviedo 1998 OroBratislava 1999 ArgentoBreslavia 2000 Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Larbi Benboudaoud (Dugny, 5 marzo 1974) è u...

Priest initiation hut in Mandaeism A tarmida initiate in the andiruna The young man in the middle, who is undergoing the tarmida initiation ceremony, is reading the Sidra ḏ-Nišmata, the first section of the Qulasta, as he sits in front of the andiruna. Part of a series onMandaeism Prophets Adam Seth Noah Shem John the Baptist Names for adherents Mandaeans Sabians Nasoraeans Gnostics Scriptures Ginza Rabba Right Ginza Left Ginza Mandaean Book of John Qulasta Haran Gawaita The Wedding of the...

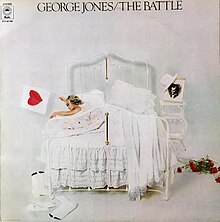

1976 studio album by George JonesThe BattleStudio album by George JonesReleasedFebruary 1976 (1976-02)RecordedOctober 1975StudioColumbia, NashvilleGenreCountryLength27:59LabelEpicProducerBilly SherrillGeorge Jones chronology Memories of Us(1975) The Battle(1976) Alone Again(1976) Singles from The Battle The BattleReleased: January 1976 You Always Look Your Best (Here in My Arms)Released: May 1976 Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllmusic linkChristgau's Record Gu...

←→Май Пн Вт Ср Чт Пт Сб Вс 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 2024 год Содержание 1 Праздники и памятные дни 1.1 Международные 1.2 Национальные 1.3 Религиозные 1.4 Именины 2 События 2.1 До XVIII века 2.2 XVIII век 2.3 XIX век 2.4 XX век 2.5 XXI век 3 Родились 3.1 До XVIII века ...

Capital of the state of Salzburg, Austria This article is about the city in Austria. For the federal state, see Salzburg (federal state). For other uses, see Salzburg (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Salzburg – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2023) (Learn ho...