Killifish

|

Read other articles:

Sulaman sutra, abad ke-17–18. Dalam koleksi Museum Tekstil (Washington, D.C.) Karpet Azerbaijan adalah karpet tradisional yang dibuat di wilayah geografis Azerbaijan. Permadani Azerbaijan adalah tekstil buatan tangan dengan berbagai ukuran, dengan tekstur padat dan permukaan bertumpuk atau tidak bertumpuk, yang polanya merupakan ciri khas banyak daerah pembuatan karpet Azerbaijan. Secara tradisional, karpet digunakan di Azerbaijan untuk menutupi lantai, menghiasi dinding interior, sofa, kur...

Architectural pattern in Ancient Egypt A typical false door to an Egyptian tomb. The deceased is shown above the central niche in front of a table of offerings, and inscriptions listing offerings for the deceased are carved along the side panels. Louvre Museum. A false door, or recessed niche,[1] is an artistic representation of a door which does not function like a real door. They can be carved in a wall or painted on it. They are a common architectural element in the tombs of ancien...

Politics of Trinidad and Tobago Government President (list) Christine Kangaloo Prime Minister Keith Rowley Parliament Senate President Nigel de Freitas House of Representatives Speaker Bridgid Annisette-George Leader of the Opposition Kamla Persad-Bissessar Judiciary Supreme Court Chief Justice: Ivor Archie Court of Appeal High Court Magistracy Family Court Privy Council committee (UK) Elections Recent elections Presidential: 201320182023 General: 20152020Next Local (Trinidad): 201320162019 ...

1965 live album by Bill CosbyWhy Is There Air?Live album by Bill CosbyReleasedAugust 1965Recorded1965Flamingo HotelLas Vegas, NevadaGenreStand-up comedyLength39:53LabelWarner Bros.ProducerAllan Sherman, Roy SilverBill Cosby chronology I Started Out as a Child(1964) Why Is There Air?(1965) Wonderfulness(1966) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllMusic[1] Why Is There Air? (1965) is Bill Cosby's third album. It was recorded at the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada. ...

Castagneto Pocomune Castagneto Po – VedutaLa piazza di Castagneto Po all'inizio del XX secolo LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regione Piemonte Città metropolitana Torino AmministrazioneSindacoDanilo Borca (lista civica) dal 27-5-2019 TerritorioCoordinate45°09′33.3″N 7°53′21.93″E / 45.159251°N 7.889425°E45.159251; 7.889425 (Castagneto Po)Coordinate: 45°09′33.3″N 7°53′21.93″E / 45.159251°N 7.889425°E45.159251; 7.8...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Чайки (значения). Чайки Доминиканская чайкаЗападная чайкаКалифорнийская чайкаМорская чайка Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:Вторич...

English football player and manager (born 1955) Richard Money Money in 2007Personal informationFull name Richard Money[1]Date of birth (1955-10-13) 13 October 1955 (age 68)[1]Place of birth Lowestoft, EnglandHeight 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m)[2]Position(s) DefenderYouth career Ipswich TownSenior career*Years Team Apps (Gls)1972-1973 Lowestoft Town 1973–1977 Scunthorpe United 173 (4)1977–1980 Fulham 106 (3)1980–1982 Liverpool 14 (0)1981 → Derby Count...

Hamlet in Chamonix, France View of Montroc, Chamonix District Montroc is a hamlet in eastern France, located in the territory of the commune of Chamonix. Several houses at Poses 150 m north-east of Montroc were destroyed on 9 February 1999 by a slab avalanche from Bec du Lachat and Mont Peclerey on the Mont Blanc massif, killing 12 people. In July, 2003, the mayor of Chamonix, Michel Charlet, received a three-month suspended prison sentence for his part in the handling of events immediat...

Canadian bank This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Bank of Hamilton – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Bank of HamiltonFounded1872Founderlocal businessmenDefunct1924FateMergedSuccessorMerged into Canadian Bank of Commerce (now mode...

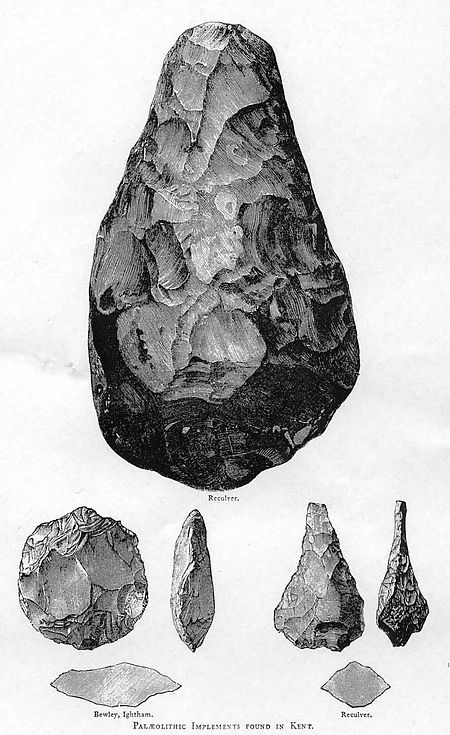

Typological classification of stone tools Not to be confused with industrial archaeology, the archaeology of (modern) industrial sites. Video of the extraction of a stone tool from a silex rock. Acheulean handaxes from Kent. The types shown are (clockwise from top) cordate, ficron, and ovate. In the archaeology of the Stone Age, an industry or technocomplex[1] is a typological classification of stone tools. An industry consists of a number of lithic assemblages, typically including a ...

Body shape similar to a human Ameca generation 1 pictured in the lab at Engineered Arts Ltd. A humanoid robot is a robot resembling the human body in shape. The design may be for functional purposes, such as interacting with human tools and environments, for experimental purposes, such as the study of bipedal locomotion, or for other purposes. In general, humanoid robots have a torso, a head, two arms, and two legs, though some humanoid robots may replicate only part of the body, for example,...

Suster ElGenre Drama Roman Skenario Endik Koeswoyo Novy Pritania Sutradara Sony Gaokasak Angling Sagaran Pemeran Adinda Azani Fauzan Nasrul Lavicky Nicholas Chand Kelvin Fendy Chow Penggubah lagu temaStevan PasaribuLagu pembukaBelum Siap Kehilangan oleh Stevan PasaribuLagu penutupBelum Siap Kehilangan oleh Stevan PasaribuPenata musikAndhika TriyadiNegara asalIndonesiaBahasa asliBahasa IndonesiaJmlh. musim1Jmlh. episode49ProduksiProduser eksekutif Fiaz Servia Riza ProduserChand Parwez S...

City in Massachusetts, United StatesNorth AdamsCityMain Street SealMotto: We Hold the Western GatewayLocation in Berkshire County and the state of Massachusetts.North AdamsLocation in the United StatesCoordinates: 42°42′N 73°7′W / 42.700°N 73.117°W / 42.700; -73.117CountryUnited StatesCommonwealthMassachusettsCountyBerkshireSettled1745Incorporated1878 (Town)Incorporated1895 (City)Government • TypeMayor-council city • MayorJennifer ...

Tedjo Sukmono Wakapuspen TNIMasa jabatan1 Oktober 2020 – 7 November 2021PendahuluTunggul SuropatiPenggantiKisdiyanto Informasi pribadiLahir(1969-05-19)19 Mei 1969Malang, Jawa TimurMeninggal7 November 2021(2021-11-07) (umur 52)Serpong, Tangerang Selatan, BantenAlma materAkademi Angkatan Laut (1991)Karier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan LautMasa dinas1991—2021Pangkat Laksamana Pertama TNINRP10073/PSatuanKorps PelautSunting kotak info • L �...

This article is about the Cyrillic letter. For its Latin-script equivalent, see Nj (digraph). For the jazz band, see The NJE. Cyrillic letter Cyrillic letter NjePhonetic usage:/ɲ/The Cyrillic scriptSlavic lettersАА̀А̂А̄ӒБВГҐДЂЃЕЀЕ̄Е̂ЁЄЖЗЗ́ЅИІЇꙆЍИ̂ӢЙЈКЛЉМНЊОО̀О̂ŌӦПРСС́ТЋЌУУ̀У̂ӮЎӰФХЦЧЏШЩꙎЪЪ̀ЫЬѢЭЮЮ̀ЯЯ̀Non-Slavic lettersӐА̊А̃Ӓ̄ӔӘӘ́Ә̃ӚВ̌ԜГ̑Г̇Г̣Г̌Г̂Г̆Г̈г̊ҔҒӺҒ̌ғ̊ӶД́Д...

中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会副主席中国人民政治协商会议会徽現任石泰峰、胡春华、沈跃跃、王勇、周强、帕巴拉·格列朗杰、何厚铧、梁振英、巴特尔、苏辉、邵鸿、高云龙、陈武、穆虹、咸辉、王东峰、姜信治、蒋作君、何报翔、王光谦、秦博勇、朱永新、杨震自2023年3月10日在任提名者全国政协(全体)会议主席团根据中共中央的建议任命者全国政协(全体)会�...

78-dimensional exceptional simple Lie group This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Algebraic structure → Group theoryGroup theory Basic notions Subgroup Normal subgroup Quotient group (Semi-)direct product Group homomorphisms kernel image direct sum wreath product simple finite infinite continuous multiplic...

1988 video game This article is about the international sequel to Super Mario Bros. For the Japanese sequel, see Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels. For other uses, see Super Mario Bros. 2 (disambiguation). Mario 2 redirects here. For other uses, see Mario II. 1988 video gameSuper Mario Bros. 2North American box artDeveloper(s)Nintendo R&D4Nintendo R&D2 (GBA)Publisher(s)NintendoDirector(s)Kensuke TanabeProducer(s)Shigeru MiyamotoDesigner(s)Kensuke TanabeYasuhisa YamamuraHideki KonnoPr...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant une localité italienne et l’Émilie-Romagne. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Salsomaggiore Terme Armoiries Drapeau Administration Pays Italie Région Émilie-Romagne Province Parme Code postal 43039 Code ISTAT 034032 Code cadastral H720 Préfixe tel. 0524 Démographie Gentilé salsési Population 20 051 hab. (31-12-2010[1]) Densité...

ليتو الأب كاز[1] الأم فويب (مثيولوجيا)[1] ذرية أبولو[1][2]، وأرتميس[3][1][2] تعديل مصدري - تعديل لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع ليتو (توضيح). ليتو هي أم الإلهان التوأم أبولو وآرتميس من زيوس، وابنة كلاً من جبابرة كايوس وفيبي.[4][5][6...