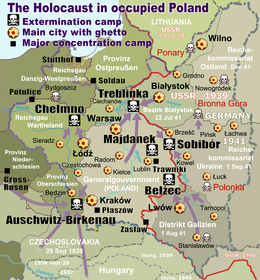

Kielce Ghetto

| |||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Kapal selam Tipe 212A U-34 berlayar Tentang kelas Pembangun:Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft GmbHFincantieri SpAOperator: Angkatan Laut Jerman Angkatan Laut ItaliaDidahului oleh:Tipe 206 (Jerman), Kelas Sauro (Italia), Kelas Ula (Norwegia)Digantikan oleh:Tipe 216Biaya:€280–560 jutaDibangun:1998–sekarangBertugas:2005–sekarangRencana:20Selesai:10Aktif:10 Ciri-ciri umum Jenis Kapal selam diesel elektrikBerat benaman 1.524 ton (mengapung)1.830 ton (menyelam)Panjang 56 m (184 ft)57,...

Demi Lovato: Stay StrongPoster promosiGenreDokumenterSutradaraDavi Russo[1]PemeranDemi LovatoNegara asalAmerika SerikatBahasa asliInggrisProduksiProduser Samantha Storr Dave Sirulnick Justin Wilkes Jonathan Mussman[2] Durasi42 menitRilis asliJaringanMTVRilis 6 Maret 2012 (2012-03-06) Demi Lovato: Stay Strong adalah sebuah film dokumenter tahun 2012 tentang penyanyi Amerika Serikat Demi Lovato yang mengisahkan pemulihannya setelah meninggalkan rehabilitasi dan kembalinya ...

GibbsitGibbsit dari BrazilUmumKategoriMineral hidroksidaRumus(unit berulang)Al(OH)3Klasifikasi Strunz04.FE.10Gibbsit atau yang dikenal juga dengan Hidrargillit, dengan rumus Al(OH)3, adalah salahsatu wujud mineral dari alumunium hidroksida. Rumusnya umumnya disebut γ-Al(OH)3 (terkadang juga α-Al(OH)3).[1] Mineral ini adalah bijih penting dalam pertambangan aluminium, seta merupakan salahsatu komposisi dari batuan bauksit. Referensi ^ N.N. Greenwood and A. Earnshaw, Chemistry of Elem...

Radio station in Devils Lake, North Dakota KZZYDevils Lake, North DakotaBroadcast areaDevils Lake-New RockfordFrequency103.5 MHzBrandingDouble Z CountryProgrammingFormatCountryAffiliationsABC News RadioUnited Stations Radio NetworksWestwood OneOwnershipOwnerDouble Z Broadcasting, Inc.Sister stationsKDLR, KDVL, KQZZHistoryFirst air date1984Call sign meaningDouble Z CountrYTechnical informationFacility ID17358ClassC1ERP100,000 wattsHAAT138 meters (453 feet)Transmitter coordinates47°58′49″N...

Untuk kapal lain dengan nama serupa, lihat Kapal Jepang Arashio. Arashio pada 21 Desember 1937 Sejarah Kekaisaran Jepang Nama ArashioDipesan 1934 (tahun fiskal)Pembangun Galangan Kapal KawasakiPasang lunas 1 Oktober 1935Diluncurkan 26 Mei 1937Mulai berlayar 30 Desember 1937Dicoret 1 April 1943Nasib Tenggelam pada 4 Maret 1943 Ciri-ciri umum Kelas dan jenis Kapal perusak kelas-AsashioBerat benaman 2.370 ton panjang (2.408 t)Panjang 111 m (364 ft) (perpendikuler) 115 m (377&...

1922 film Saturday NightFilm posterDirected byCecil B. DeMilleWritten byJeanie MacPhersonScreenplay byJeanie MacPhersonStory byJeanie MacPhersonProduced byCecil B. DeMilleStarringLeatrice JoyConrad NagelEdith RobertsCinematographyKarl StrussAlvin WyckoffEdited byAnne BauchensProductioncompanyFamous Players–Lasky CorporationDistributed byParamount PicturesRelease date January 29, 1922 (1922-01-29) Running time9 reelsCountryUnited StatesLanguageSilent (English intertitles)Budge...

Chilean painter Ximena ArmasSecrets by Ximena Armas.BornXimena Armas Fernández (1946-07-29) 29 July 1946 (age 77)Santiago, ChileNationalityChileanEducation Escuela de Bellas Artes at the Universidad de Chile Escuela de Artes at the Universidad Católica de Chile École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris SpouseHenri RicheletPatron(s)Mario Carreño and Mario Toral Websitehttp://ximena.armas.2.free.fr Ximena Armas (born ...

American politician and judge This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Edward G. Biester Jr. – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2021) (Learn how and when...

Sculpture by Tony Lopez in Houston, Texas, U.S. Bust of José MartíBust of José Martí in May 2023ArtistTony LopezYear1981TypeSculptureMediumBronze (sculpture)Granite (pedestal)SubjectJosé MartíLocationHouston, Texas, United StatesCoordinates29°43′05″N 95°23′02″W / 29.71802°N 95.38386°W / 29.71802; -95.38386OwnerCity of HoustonWebsiteJose Martí (with photo)l An outdoor bust of José Martí by Cuban artist Tony Lopez is installed at Hermann Park's[1...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Certaines informations figurant dans cet article ou cette section devraient être mieux reliées aux sources mentionnées dans les sections « Bibliographie », « Sources » ou « Liens externes » (juillet 2016). Vous pouvez améliorer la vérifiabilité en associant ces informations à des références à l'aide d'appels de notes. Pour les articles homonymes, voir Cronin. A. J. Cr...

هذه المقالة تحتاج للمزيد من الوصلات للمقالات الأخرى للمساعدة في ترابط مقالات الموسوعة. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة وصلات إلى المقالات المتعلقة بها الموجودة في النص الحالي. (يونيو 2016) صمويل فوكس معلومات شخصية الميلاد 17 يونيو 1815(1815-06-17) تاريخ الوفاة 25 فبراير 1887 (71 س�...

Este artículo o sección tiene referencias, pero necesita más para complementar su verificabilidad. Busca fuentes: «Vertedero (basura)» – noticias · libros · académico · imágenesEste aviso fue puesto el 28 de abril de 2022. Se ha sugerido que este artículo o sección sea fusionado con Nombre de hasta otros veinte artículos para fusionar separados por y . Para más información, véase la discusión.Una vez que hayas realizado la fusión de contenidos, pide la ...

2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会波兰代表團波兰国旗IOC編碼POLNOC波蘭奧林匹克委員會網站olimpijski.pl(英文)(波兰文)2020年夏季奥林匹克运动会(東京)2021年7月23日至8月8日(受2019冠状病毒病疫情影响推迟,但仍保留原定名称)運動員206參賽項目24个大项旗手开幕式:帕维尔·科热尼奥夫斯基(游泳)和马娅·沃什乔夫斯卡(自行车)[1]闭幕式:卡罗利娜·纳亚(皮划艇)&#...

United States destroyer tender For other ships with the same name, see USS Bridgeport. USS Bridgeport (Id. No. 3009) at New York on 1 October 1917. She was originally the German liner SS Breslau. History Germany NameSS Breslau NamesakeBreslau, Germany (today Wrocław, Poland) OwnerNorth German Lloyd Builder Bremer Vulkan Vegesack, Germany Laid down1901 Launched14 August 1901[1] Maiden voyage23 November 1901 to New York[1] Route Bremen–Baltimore, April 1902 Bremen–Baltimore...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

PSG's team in 2014–15. Paris Saint-Germain Football Club are a French professional football club based in Paris. Founded in 1971, following the green light given by the French Football Federation (FFF) to women's football, they compete in the Division 1 Féminine, the top division of French football. Since their inception, PSG have played 52 seasons, all of them within the top three levels of the French football league system: Division 1, Division 2 and Ligue de Paris. PSG signed 33 women ...

Literary genre, work of literature featuring supernatural elements For other uses, see Ghost Story (disambiguation). Illustration by James McBryde for M. R. James's story Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad (1904). Fantasy Media Anime Art Artists Authors Comics Films Podcasts Literature Magazines Manga Publishers Light novels Television Webcomics Genre studies Creatures History Early history Magic Magic item Magic system Magician Mythopoeia Tropes Fantasy worlds Campaign settings Sub...

Mucuna Mucuna poggei Klasifikasi ilmiah Domain: Eukaryota Kerajaan: Plantae (tanpa takson): Tracheophyta (tanpa takson): Angiospermae (tanpa takson): Eudikotil (tanpa takson): Rosid Ordo: Fabales Famili: Fabaceae Subfamili: Faboideae Tribus: Phaseoleae Genus: MucunaAdans.[1] Spesies Lihat teks Sinonim[1][2] Homotipik: Hornera Neck. ex A.Juss. (1821), nom. superfl. Heterotipik: Cacuvallum Medik. (1787) Carpopogon Roxb. (1827) Citta Lour. (1790) Labradia Swediaur (1801)...

U.S. founding document inkstand Syng inkstandArtistPhilip SyngYear1752; 272 years ago (1752)Typesilver inkstandLocationIndependence National Historical Park, Philadelphia John Hancock used the inkstand to write his well-known signature on the Declaration of Independence Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, by Howard Chandler Christy (1940), shows the inkstand. John Henry Hintermeister's 1925 painting Foundation of American Government portrays the in...

Iranian-Kurdish tribe Šwānkāraشوانکارە1030–1424Map of Iran during Anarchy Era 1328-1384 AD. Shabankara in purple.CapitalIj (Ig)Common languagesKurdish PersianReligion Sunni IslamGovernmentMonarchy (princely confederation)Amir/Malik • 1030-1078 Fadluya• c.1310 (?)-1355 Ardashir History • Established 1030• Shabankara overthrown by Timurids 1424 Preceded by Succeeded by Buyid dynasty Timurid Empire Muzaffarid dynasty Shabankara or Shwankara...