John Forbes (British Army officer)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

2022 studio album by KasabianThe Alchemist's EuphoriaStudio album by KasabianReleased12 August 2022 (2022-08-12)StudioThe Sergery, Leicester, EnglandGenre Rock techno[1] Length38:05LabelSonyProducer Serge Pizzorno Fraser T. Smith Kasabian chronology For Crying Out Loud(2017) The Alchemist's Euphoria(2022) Happenings(2024) Singles from The Alchemist's Euphoria AlygatyrReleased: 26 October 2021 ScriptvreReleased: 6 May 2022 ChemicalsReleased: 3 June 2022 The Wall...

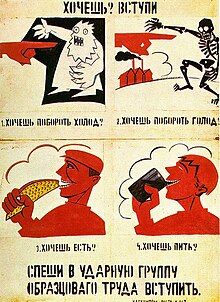

Contoh Agitprop Agitprop (Rusia: агитпроп) adalah akronim dari agitasi dan propaganda.[1] Istilah ini berasal dari Bolshevist Rusia (kemudian bernama Uni Soviet), di mana istilah adalah bentuk singkat dari отдел агитации и пропаганды (otdel agitatsii i propagandy), yakni, Departemen Agitasi dan Propaganda yang merupakan bagian dari pusat atau daerah komite dari Partai Komunis Uni Soviet. Departemen ini dikemudian hari berubah nama menjadi Departemen Ide...

Keiller's marmaladeTypeMarmaladePlace of originScotlandRegion or stateDundeeCreated byJanet KeillerMain ingredientsOranges Keiller's marmalade is a Scottish marmalade, believed to have been the first commercial brand made in Great Britain. It was first manufactured by James Keiller in Dundee, Scotland, later creating James Keiller & Son, a brand name which became iconic in the 18th and 19th centuries, and has been sold several times. History According to a legend, in the 18th century, Ja...

Перуанский анчоус Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеГруппа:Костные рыбыКласс:Лучепёрые рыбыПодкласс:Новопёрые �...

Concept of non-human beings disguised as human For the first time Psyche sees the true form of her lover Eros; darkness had hidden his wings A human disguise (also human guise and sometimes human form)[1] is a concept in fantasy, folklore, mythology, religion, literature, iconography, and science fiction whereby non-human beings such as gods, angels, monsters, extraterrestrials, or robots are disguised to seem human.[2][3] Stories have depicted the deception as a means...

内華達州 美國联邦州State of Nevada 州旗州徽綽號:產銀之州、起戰之州地图中高亮部分为内華達州坐标:35°N-42°N, 114°W-120°W国家 美國建州前內華達领地加入聯邦1864年10月31日(第36个加入联邦)首府卡森城最大城市拉斯维加斯政府 • 州长(英语:List of Governors of {{{Name}}}]]) • 副州长(英语:List of lieutenant governors of {{{Name}}}]])喬·隆巴爾多(R斯塔...

1946 film by Edgar George Ulmer The Wife of Monte CristoDirected byEdgar G. UlmerScreenplay byDorcas Cochran Edgar G. UlmerBased onThe Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre DumasProduced byLeon FromkessStarringJohn LoderLenore Aubert Fritz KortnerCinematographyEdward A. KullEdited byDouglas W. BagierMusic byPaul DessauProductioncompanyProducers Releasing CorporationDistributed byProducers Releasing CorporationRelease date April 23, 1946 (1946-04-23) Running time83 minutesCountryUn...

Historic site in Split, CroatiaHistorical Complex of Split with the Palace of DiocletianNative name Croatian: Povijesna jezgra grada Splita s Dioklecijanovom palačomView of the Peristyle (the central square within the Palace) towards the entrance of Diocletian's quartersLocationSplit, CroatiaCoordinates43°30′30″N 16°26′24″E / 43.50833°N 16.44000°E / 43.50833; 16.44000Built4th century AD UNESCO World Heritage SiteTypeCulturalCriteriaii, iii, ivDesignated19...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع لواء (توضيح). لواء الرتبة الأعلى فريق الرتبة الأدنى عميد، وعقيد تعديل مصدري - تعديل رتبة لواء هي رتبة عسكرية في الكثير من البلدان معظم جيوش بلدان الكومنولث وعدد من الدول العربية[1][2][3][4] واليابان وألمانيا والولايات المت�...

Альберт Ейнштейн, один з найвизначніших фізиків, який створив теорію відносності Фі́зик — людина, котра досліджує фізику. Це слово можна вживати стосовно науковця або вчителя(-ки), студента(-ки) тощо. Науковців-фізиків поділяють на теоретиків та експериментаторів. Фіз�...

Victor Horta (بالهولندية: Victor Petrus Horta) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 6 يناير 1861(1861-01-06)غنت، بلجيكا الوفاة 8 سبتمبر 1947 (عن عمر ناهز 86 عاماً)إقليم بروكسل العاصمة، بلجيكا الجنسية بلجيكا الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم الأكاديمية الملكية للفنون الجميلة [لغات أخرى] المهنة مهند�...

American politician Chip LaMarcaMember of the Florida House of Representativesfrom the 100th districtIncumbentAssumed office November 6, 2018Preceded byGeorge MoraitisMember of the Broward County Commissionfrom the 4th districtIn officeNovember 2010 – November 6, 2018Preceded byKen KeechlSucceeded byLamar Fisher Personal detailsBorn (1968-03-16) March 16, 1968 (age 56)Winchester, Massachusetts, U.S.Political partyRepublicanSpouseEileen LaMarcaEducationBroward C...

我的如意狼君Bottled Passion类型民初倫理、愛情编剧石凱婷、楊雪兒、黎家明、霍婉君、張靜雯编导方駿釗、陳湘娟、梁耀堅、施俊傑助理编导黃升愷、張永輝、尹之維、胡家斌、李鳳明、郭家禧、陳祉茵、杜瑞榕主演周麗淇、黃浩然、姚子羚、龔嘉欣、曹永廉、姚嘉妮、陳秀珠、郭 峰、陳山聰、胡諾言、程可為、蔡淇俊、李天翔、趙永洪、葉翠翠、李成昌、方伊琪国家/�...

City in Tennessee, United StatesMcMinnville, TennesseeCityCourthouse SquareLocation of McMinnville in Warren County, Tennessee.Coordinates: 35°41′12″N 85°46′46″W / 35.68667°N 85.77944°W / 35.68667; -85.77944CountryUnited StatesStateTennesseeCountyWarrenFoundedAugust 4, 1810Incorporated1868[1]Named forJoseph McMinnGovernment • TypeMayor and Board of Aldermen • MayorRyle ChastainArea[2] • Total11.06 sq...

1905 China filmDingjun MountainChinese nameTraditional Chinese定軍山Simplified Chinese定军山TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinDìngjūn Shān Directed byRen QingtaiStarringTan XinpeiCinematographyLiu ZhonglunProductioncompanyFengtai PhotographyRelease date 1905 (1905) CountryChinaLanguageMandarin Dingjun Mountain was a 1905 Chinese silent film directed by Ren Qingtai (任慶泰) a.k.a. Ren Jingfeng (任景豐), who was assisted by his cinematographer Liu Zhonglun...

1939 film directed by William C. McGann Lincoln in the White HouseFrank McGlynn Sr. (right) asLincoln in the 1939 shortDirected byWilliam McGann[1]Written byCharles TedfordStarringFrank McGlynn, Sr.Dickie MooreCinematographyWilfred M. Cline[2]Natalie Kalmus[1] (color)Edited byEverett DoddMusic byHoward Jackson(uncredited)ProductioncompanyWarner Bros.Distributed byWarner Bros.Release date February 11, 1939 (1939-02-11) Running time21 minutesCountryUnited ...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant un homme politique et un militaire vietnamien. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Dương Văn Minh Fonctions Président du Conseil militaire révolutionnaire de la république du Viêt Nam(chef de l'État) 2 novembre 1963 – 30 janvier 1964 (2 mois et 28 jours) Prédécesseur Ngô Đình Diệm (président de la République) Successeur Nguyên Khan...

Pulau PanggungKecamatanNegara IndonesiaProvinsiLampungKabupatenTanggamusPemerintahan • Camat-Populasi • Total- jiwaKode Kemendagri18.06.04 Kode BPS1802030 Luas- km²Desa/kelurahan21 pekon Patung megalitik di Pulau Panggung (foto diambil tahun 1931) Untuk tempat lain yang bernama sama, lihat Pulau Panggung. Pulau Panggung adalah sebuah kecamatan di Kabupaten Tanggamus, Lampung, Indonesia. Arkeologi Di Pulau Panggung terdapat beberapa situs megalitik, di antaranya s...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。 出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: 国王 – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL (2017年3月) 欧州の貴族階級 皇帝 / 女皇 / 王・皇帝 / 女王・女皇 / ...

Part of a series onCannabis ArtsCulture 420 (chan) Books Magu (deity) Names Religion Judaism Latter-day Saints Sikhism Smoke-in Spiritual use Sports Stoner film Stoner rock Terms Chemistry Phytocannabinoids Main THC Dronabinol (INN) CBD Minor delta-8-THC delta-10-THC THCH THCP CBDH CBDP Semi-synthetic cannabinoids THC-O-acetate Synthetic cannabinoids AM AM-2201 CP CP-55940 Nabilone Dimethylheptylpyran HU HU-210 HU-331 JWH JWH-018 JWH-073 JWH-133 Levonantradol MDMB-CHMICA SR144528 WIN 55,212-...