Jeremy Larner

|

Read other articles:

Dusit InternationalJenisPublikKode emitenSET: DTCIndustriHospitalitasDidirikan1948PendiriThanpuying Chanut PiyaouiKantorpusatBangkok, ThailandCabang29TokohkunciSuphajee Suthumpun, CEO Grup [1]:6JasaDusit Thani CollegeLe Cordon BleuDevarana SpaPendapatanTHB.5.425 juta (2016)[1]:8Laba bersihTHB.114 juta(2016)[1]:8Karyawan3.792[1]:58DivisiDusit Thani HotelsDusit Princess Hotelsdusit D2 HotelsDusit Residence Serviced ApartmentsDusit Devarana HotelsSitus webwww.dusi...

Imogiri Hanacaraka: ꦲꦶꦩꦒꦶꦫꦶTransliterasi: ImagiriKapanewonPeta lokasi Kapanewon ImogiriNegara IndonesiaProvinsiDaerah Istimewa YogyakartaKabupatenBantulPemerintahan • PanewuDrs. Mistabakhul MunirPopulasi • Total56,357 jiwaKode Kemendagri34.02.10 Kode BPS3402090 Luas54,49 km²Desa/kelurahan8Situs webkec-imogiri.bantulkab.go.id Imogiri (Jawa: ꦲꦶꦩꦒꦶꦫꦶ, translit. Imagiri) adalah sebuah kapanewon di Kabupaten Bantul, Provinsi Daerah...

Rionardo Kapusdatin KemhanPetahanaMulai menjabat 19 April 2022 Informasi pribadiLahir4 Agustus 1971 (umur 52)Menado, IndonesiaKebangsaanIndonesiaAlma materAkademi Militer (1994)Karier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan DaratMasa dinas1994—sekarangPangkat Brigadir Jenderal TNISatuanInfanteri (Kopassus)Sunting kotak info • L • B Brigadir Jenderal TNI Rionardo (lahir 4 Agustus 1971) adalah seorang perwira tinggi TNI-AD yang sejak 19 April 2022 meng...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Januari 2023. SDN Klender 12Sekolah Dasar Negeri Klender 12InformasiJenisNegeriNomor Statistik Sekolah101016403912Nomor Pokok Sekolah Nasional20108584Jumlah siswa207 2010StatusAktifAlamatLokasiJln.Petanian Utara, Jakarta Timur, DKI Jakarta, IndonesiaSitus ...

For the fast-food chain, see Marugame Seimen. City in Shikoku, JapanMarugame 丸亀市CityView of downtown Marugame City, from Marugame Castle FlagChapterLocation of Marugame in Kagawa PrefectureMarugameLocation in JapanCoordinates: 34°17′N 133°48′E / 34.283°N 133.800°E / 34.283; 133.800CountryJapanRegionShikokuPrefectureKagawaGovernment • MayorKyoji Matsunaga (from April 2021)Area • Total111.79 km2 (43.16 sq mi)Population...

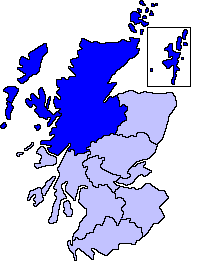

Northern part of Scotland For other uses, see Highlands and Islands. Not to be confused with The Northern Scot. Northern Scotland shown within Scotland This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Northern Scotland – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The t...

Cell-mediated killing of other cells mediated by antibodiesAntibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), also referred to as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, is a mechanism of cell-mediated immune defense whereby an effector cell of the immune system kills a target cell, whose membrane-surface antigens have been bound by specific antibodies.[1] It is one of the mechanisms through which antibodies, as part of the humoral immune ...

Gediminas Hill LiftOverviewStatusIn serviceLocaleVilniusStations2Websitehttp://www.lnm.lt/darbo-laikas/ServiceTypeInclined elevatorServices1Operator(s)Vilniaus pilių valstybinio kultūrinio rezervato direkcijaRolling stock1 ABS Transportbahnen (Doppelmayr Garaventa Group)HistoryOpened2003TechnicalLine length65 m (213 ft)Number of tracks1Character1Track gauge1,200 mm (3 ft 11+1⁄4 in)Operating speed2 m/s (4.5 mph) Gediminas Hill Lift (Lithuanian: K...

Shrimp dish Coconut shrimp with a dipping sauce Coconut shrimp is a shrimp dish prepared using shrimp and coconut as primary ingredients. It can be prepared as a crunchy dish with the shrimp coated and deep fried, pan-fried or baked, and as a sautéed dish using coconut milk and other ingredients. It can be prepared and served on skewers. Crunchy Crunchy coconut shrimp is typically prepared using shrimp that are coated with flour, placed in an egg wash, coated with a flaked coconut and bread ...

311th Wing redirects here. For the reconnaissance unit 311th Photographic Wing, see 311th Air Division. 311th Human Systems Wing An international health specialist of the 311th Human Systems Wing speaks with a woman in Uganda during exercise Natural Fire 2006.Active1961–2009Country United StatesBranch United States Air ForceRoleHuman factors research and developmentPart ofAir Force Materiel CommandMotto(s)Perscrutari, Docere. Mederi Latin (1961–1974) Investigate, Teach, Hea...

Weekly newspaper published in Alexander City, Alabama Alexander City OutlookTypeTwice-weekly newspaperFormatBroadsheetOwner(s)Boone NewspapersFounder(s)Capt. J.D. DicksonPublisherSteve BakerEditorKaitlin FlemingFounded1892 (1892)LanguageEnglishHeadquartersAlexander City, AlabamaCirculation2,050ISSN0738-5110OCLC number9612603 Websitealexcityoutlook.com The Alexander City Outlook is a twice weekly newspaper publication in eastern Alabama. The Outlook has been in constant publication since ...

يوم جديد في صنعاء القديمةA New Day in Old Sana'a (بالإنجليزية) معلومات عامةالصنف الفني فيلم دراما تاريخ الصدور 2005مدة العرض 86 د.اللغة الأصلية العربية والإنجليزيةالبلد اليمنالطاقمالمخرج بدر بن حرسيالكاتب بدر بن حرسيالتصوير Muriel Aboulroussصناعة سينمائيةالمنتج Felix Films Entertainment Limited، Yemen Med...

تعتمد هذه المقالة بصورة رئيسة على استشهادات بمصادر أولية. قد يكون هنالك نقاشٌ ذو علاقةٍ في صفحة النقاش المتعلّقة. فضلاً ساهم في تحسينها بإضافة مصادر ثانوية وثالثية. (يوليو 2024) توثيق القالب[عرض] [عدّل] [تاريخ] [محو الاختزان] [استخدامات] هذا قالب لصيانة الم�...

Artikel ini bukan mengenai xerofit. Xerophyta adalah genus dari famili Velloziaceae (ratifikasi tahun 1789).[1][2] Genus ini berhabitat di Afrika, Madagaskar, dan Semenanjung Arab.[3] Xerophyta Xerophyta retinervisTaksonomiKerajaanPlantaeDivisiTracheophytaOrdoPandanalesFamiliVelloziaceaeGenusXerophyta Juss., 1789 Spesies Xerophyta acuminata Xerophyta andringitrensis Xerophyta arabica Xerophyta argentea Xerophyta capillaris Xerophyta concolor Xerophyta connata Xerophyta...

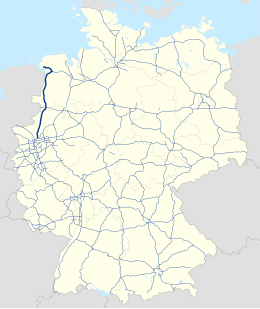

Bundesautobahn 31 EmslandautobahnLocalizzazioneStato Germania DatiClassificazioneAutostrada InizioEmden FineBottrop Lunghezza220 km PercorsoLocalità serviteMeppen Principali intersezioni Strade europee Manuale La Bundesautobahn 31, abbreviata anche in BAB 31, è una autostrada tedesca che si sviluppa tra la Renania Settentrionale-Vestfalia e la Bassa Sassonia ed è il principale asse di collegamento tra i paesi del Nord-Ovest della Germania con la regione della Ruhr. Il percorso inizia ...

Anthony Weiner, Congressional portrait, c. 2007 Anthony Weiner is a former member of the United States House of Representatives from New York City who has been involved in multiple sex scandals related to sexting. The first scandal began when Weiner was a Democratic U.S. Congressman. He used the social media website Twitter to send a link that contained a sexually suggestive picture of himself to a 21-year-old woman. After initially denying reports that he had posted the image, he admi...

Questa voce sugli argomenti circondari della Germania e Sassonia-Anhalt è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Circondario di Weißenfelscircondario(DE) Landkreis Weißenfels LocalizzazioneStato Germania Land Sassonia-Anhalt DistrettoNon presente AmministrazioneCapoluogoWeißenfels TerritorioCoordinatedel capoluogo51°12′N 11°58′E51°12′N, 11°58′E (Circondario di Weißenfels) Abitanti41 604 (31-12-2006) Altre in...

Inpumon'in no Tayū dallo Ogura Hyakunin isshu Inpumon'in no Tayū (殷富門院大輔, L'inserviente dell'Imperatrice Inpu; 1130 – 1200) è stata una poeta giapponese waka del tardo periodo Heian e il primo periodo Kamakura. È considerata una delle Trentasei poetesse immortali (女房三十六歌仙, Nyōbō Sanjūrokkasen). Suo padre era Fujiwara no Nobunari e sua madre era la figlia di Sugawara no Ariyoshi. Servì come dama di corte della principessa imperiale Ryōshi (conosciuta come I...

此條目介紹的是前中共中央總書記胡錦濤之子。关于中國男演員,请见「胡海峰 (演員)」。 胡海峰 中华人民共和国民政部副部长现任就任日期2024年1月16日与唐承沛、张春生、詹成付、李保俊同时在任部长陆治原 个人资料出生 (1972-11-06) 1972年11月6日(51歲) 中国甘肃省籍贯江苏省泰縣(今属泰州市)国籍 中华人民共和国政党 中国共产党配偶王珺父母胡�...

Questa voce sull'argomento stagioni delle società calcistiche italiane è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Voce principale: Associazione Sportiva Dilettanti Carbonia Calcio. Gruppo Sportivo CarbosardaStagione 1951-1952Sport calcio Squadra Carbosarda Allenatore Stefano Perati Presidente Fernando Fioretti Serie C9º posto nel girone C. Retrocesso in IV Serie. 1950-1951 1952-1953 Si invi...