Hough, Cleveland

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 to 1957 For the eponymous hat, see Anthony Eden hat. The Right HonourableThe Earl of AvonKG MC PCPrime Minister of the United KingdomIn office6 April 1955 – 9 January 1957MonarchElizabeth IIPreceded byWinston ChurchillSucceeded byHarold MacmillanLeader of the Conservative PartyIn office6 April 1955 – 10 January 1957Chairman The Viscount Woolton The Lord Poole Preceded byWinston ChurchillSucceeded byHarold MacmillanDe...

Questa voce sull'argomento stagioni delle società calcistiche italiane è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Voce principale: Associazione Sportiva Dilettantistica Junior Biellese Libertas. Associazione Sportiva BielleseStagione 1951-1952Sport calcio Squadra Biellese Allenatore Giovanni Costanzo Presidente Luigi Fila Serie C16º posto nel girone A. Retrocesso in IV Serie. 1950-1951 1952...

Liga 2Musim2023–2024Tanggal10 September 2023 – 9 Maret 2024JuaraPSBS BiakPromosi PSBS Biak Semen Padang Malut United Degradasi PSCS Cilacap Kalteng Putra FC Sulut United FC Persiba Balikpapan PSDS Deli Serdang Persikab Bandung Perserang Serang Sada Sumut FC Jumlah pertandingan262Jumlah gol624 (2,38 per pertandingan)Pencetak golterbanyak Alexsandro Ferreira dos Santos (15 gol)Kemenangan kandangterbesarNusantara 7-3 PSDS(6 Januari 2024)Persiraja 5-1 PSDS(11 Desember 2023)Semen Padang 4...

Voce principale: Associazione Sportiva Pro Gorizia. Associazione Sportiva Pro GoriziaStagione 1940-1941Sport calcio Squadra Pro Gorizia Presidente Aldo Paolo Tacchini Serie C13º posto nel girone A. 1939-1940 1941-1942 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti l'Associazione Sportiva Pro Gorizia nelle competizioni ufficiali della stagione 1940-1941. Rosa N. Ruolo Calciatore D Ermenegildo Blason D Ivano Blason C Bruno Ciuffarin A B. Culot D ...

Belgian cyclist Lucien Van ImpeVan Impe at the 1975 Acht van ChaamPersonal informationFull nameLucien Van ImpeNicknamede kleine van MereBorn (1946-10-20) 20 October 1946 (age 77)Mere, BelgiumTeam informationCurrent teamRetiredDisciplineRoadRoleRiderRider typeClimbing specialistProfessional teams1969–1974Sonolor–Lejeune1975–1976Gitane–Campagnolo1977Lejeune–BP1978C&A1979Kas–Campagnolo1980Marc–Carlos–V.R.D.–Woningbouw1981Boston–Mavic1982-1984Metauro Mo...

1942 unfinished opera by Dmitri Shostakovich For the Prokofiev opera, see The Gambler (Prokofiev). The GamblersUnfinished opera by Dmitri ShostakovichDmitri Shostakovich in 1950Native titleRussian: Игроки, romanized: IgrokiLibrettistShostakovichLanguageRussianBased onThe Gamblersby Nikolai GogolPremiere18 September 1978 (1978-09-18) (concert performance)Leningrad Conservatory The Gamblers (Russian: Игроки, romanized: Igroki), Op. 63, is an unfinished opera...

Sculpture by Philip Jackson in Westminster, London Statue of Mahatma GandhiThe statue in 2015ArtistPhilip JacksonYear2015; 9 years ago (2015)TypeSculptureMediumBronzeSubjectMahatma GandhiDimensions270 cm (110 in)LocationLondon, SW1United KingdomCoordinates51°30′02″N 0°07′38″W / 51.500570°N 0.127241°W / 51.500570; -0.127241 The statue of Mahatma Gandhi in Parliament Square, Westminster, London, is a work by the sculptor Philip...

Kekurangan bensin memicu krisis bahan bakar selama blokade. Blokade Nepal 2015 yang dimulai pada tanggal 23 September 2015 adalah krisis ekonomi dan kemanusiaan yang mempengaruhi Nepal dan ekonominya. Pemerintah Nepal menuduh bahwa India telah melakukan blokade.[1] India menampik tuduhan tersebut dan menyatakan bahwa kekurangan persediaan dipicu oleh demonstrasi Madheshi di Nepal. Namun, sedikitnya jumlah truk bahan bakar yang masuk di perbatasan memperkuat tuduhan bahwa India telah m...

For other uses, see Saramandaia. Brazilian TV series or program SaramandaiaGenreTelenovelaDramaComedyRomanceThrillerCreated byRicardo LinharesBased onSaramandaiaby Dias GomesDeveloped byRicardo LinharesDirected by Denise Saraceni Fabrício Mamberti Starring Lília Cabral Jose Mayer Débora Bloch Gabriel Braga Nunes Sérgio Guizé Leandra Leal Matheus Nachtergaele Fernanda Montenegro Tarcísio Meira Marcos Palmeira Vera Holtz Aracy Balabanian Renata Sorrah Ana Beatriz Nogueira Marcos Pasquim O...

Barangay in Makati City, Metro Manila, Philippines Barangay in National Capital Region, PhilippinesForbes ParkBarangayGate along EDSA Map of Makati with Forbes Park highlightedCountryPhilippinesRegionNational Capital RegionCityMakatiDistrictPart of the 1st district of MakatiFounded1940sNamed forWilliam Cameron ForbesGovernment • TypeBarangay • Barangay CaptainEvangeline Manotok • Barangay Councilors Members Ana Maria BorromeoMaria Micaela RemullaMarcus Lesl...

Java-based GUI toolkit Example Swing widgets in Java Swing is a GUI widget toolkit for Java.[1] It is part of Oracle's Java Foundation Classes (JFC) – an API for providing a graphical user interface (GUI) for Java programs. Swing was developed to provide a more sophisticated set of GUI components than the earlier Abstract Window Toolkit (AWT). Swing provides a look and feel that emulates the look and feel of several platforms, and also supports a pluggable look and feel tha...

Questa voce sull'argomento centri abitati del Nottinghamshire è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Newark-on-Trentparrocchia civile Newark-on-Trent – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Regno Unito Inghilterra RegioneMidlands Orientali Contea Nottinghamshire DistrettoNewark and Sherwood TerritorioCoordinate53°04′N 0°48′W / 53.066667°N 0.8°W53.066667; -0.8 (Newark-on-Trent)Coordinate: 53°0...

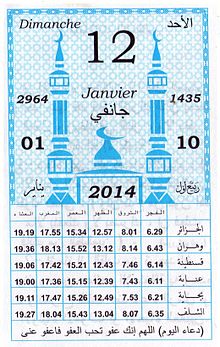

طالع أيضًا: تقويم قبطي هذه المقالة بحاجة لمراجعة خبير مختص في مجالها. يرجى من المختصين في مجالها مراجعتها وتطويرها. (أبريل 2014)Learn how and when to remove this message ورقة رزنامة جزائرية موافقة لأول أيام السنة الأمازيغية (عجمية) رزنامة لليوم الأول من السنة الأمازيغية الموافقة آنذاك ل 14 جانف�...

Частина серії проФілософіяLeft to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, AverroesПлатонКантНіцшеБуддаКонфуційАверроес Філософи Епістемологи Естетики Етики Логіки Метафізики Соціально-політичні філософи Традиції Аналітична Арістотелівська Африканська Близькосхідна іранська Буддій�...

هذه المقالة عن الجزيرة كشكل من أشكال السطح. لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع جزيرة (توضيح). جزيرةمعلومات عامةصنف فرعي من شكل الأرضيابسةمكان الشاغل islanders (en) تصنيف للتصنيفات التي تحمل هذا الاسم تعديل - تعديل مصدري - تعديل ويكي بيانات جزيرة الجزيرة (الجمع: جَزَائِر أو جُزُر) هي منطقة من ...

American historian and political philosopher (1918–2015) Harry V. JaffaBornHarry Victor Jaffa(1918-10-07)October 7, 1918New York City, New York, U.S.DiedJanuary 10, 2015(2015-01-10) (aged 96)[5]Pomona, California, U.S.Spouse Marjorie Etta Butler (m. 1942; died 2010)Academic backgroundEducationYale University (BA)The New School (PhD)ThesisThomism and Aristotelianism (1950)Doctoral advisorLeo StraussInfluencesWalter Berns&#...

Bank Bumi ArtaJenisPublikKode emitenIDX: BNBAIndustriJasa keuanganPendahuluBank Duta NusantaraDidirikan1967Kantorpusat Jakarta, IndonesiaTokohkunciRachmat Mulia Suryahusada (Presiden Komisaris)PemilikAjaib Group (24%)Situs webwww.bankbba.co.id Bank Bumi Arta (IDX: BNBA) adalah perusahaan Indonesia yang berbentuk perseroan terbatas dan bergerak di bidang jasa keuangan perbankan. Bank ini berbasis di Jakarta dan didirikan pada tahun 1967. Bank Bumi Arta melakukan merger dengan Bank Duta Nusanta...

Cet article recense les sites inscrits au patrimoine mondial au Brésil. Statistiques Le Brésil accepte la Convention pour la protection du patrimoine mondial, culturel et naturel le 1er septembre 1977[1]. Le premier site protégé est inscrit en 1980[2]. En 2021, le Brésil compte 23 sites inscrits au patrimoine mondial, 15 culturels, 7 naturels et 1 mixte. Le pays a également soumis 22 sites à la liste indicative, 10 culturels, 10 naturels et 2 mixtes. Listes Patrimoine mondial Les sites...

English football club Football clubSawbridgeworth TownFull nameSawbridgeworth Town Football ClubNickname(s)RobinsFounded1897GroundCrofters End, SawbridgeworthCapacity2,500 (175 seated)[1]ChairmanSteve DayManagerKieran Amos & Alex SalmonLeagueEssex Senior League2023–24Spartan South Midlands League Premier Division, 19th of 19 (transferred) Home colours Away colours Sawbridgeworth Town Football Club is an English football club based in Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire. The club are c...

Awake Serie de televisión Género Serie de televisión de fantasíaFicción procedimentalDrama televisivoCreado por Kyle KillenProtagonistas Jason IsaacsDylan MinnetteLaura AllenBD WongCherry JonesMichaela McManusSteve HarrisWilmer ValderramaCompositor(es) Reinhold HeilPaís de origen Estados UnidosIdioma(s) original(es) InglésN.º de temporadas 1N.º de episodios 13 (lista de episodios)ProducciónProductor(es) ejecutivo(s) David Slade (Piloto)Kyle KillenHoward GordonJeffrey ReinerProductor...