Hampshire (UK Parliament constituency)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Aslim TadjuddinLahir30 Desember 1949 (umur 74)Payakumbuh, Sumatera Barat, IndonesiaKebangsaanIndonesiaPekerjaanEkonom Aslim Tadjuddin (lahir 30 Desember 1949) adalah seorang ekonom dan mantan deputi gubernur Bank Indonesia. Saat ini ia menjabat sebagai komisaris utama PT Emco Asset Management.[1] Kehidupan Aslim merupakan putra Minangkabau dari nagari VII Koto Talago, Lima Puluh Kota, Sumatera Barat.[2] Ia memperoleh gelar sarjana dari Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Andala...

Danau Macquarie Kota Lake Macquarie adalah wilayah pemerintahan lokal di Wilayah Hunter, New South Wales, Australia dan dinyatakan sebagai kota pada 7 September 1984. Area ini terletak bersebelahan dengan kota Newcastle dan merupakan bagian dari Greater Newcastle Area.[1] Kota ini terletak 150 km (93 mi) di utara Sydney. Salah satu atraksi wisata utamanya adalah danaunya, yang juga dinamai Danau Macquarie. Kota dan desa utama Belmont Cardiff Charlestown Cooranbong Glendale M...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (نوفمبر 2019) الدوري النمساوي 2002–03 تفاصيل الموسم الدوري النمساوي النسخة 92 البلد النمسا المنظم اتحاد النمسا ...

Perbandingan pangkat militer Script error: The function "infoboxTemplate" does not exist. lbs Pangkat Letnan Dua dalam TNI-AD Letnan Dua (disingkat Letda) adalah pangkat terendah dalam jenjang perwira pertama di kemiliteran di Indonesia. Diberikan kepada: Taruna Akademi Militer (Akmil), Akademi Angkatan Laut (AAL) dan Akademi Angkatan Udara (AAU) yang telah menyelesaikan pendidikan selama empat tahun. Bintara yang mendapat promosi ke jenjang perwira melalui Pendidikan Pembentukan P...

Ramón Sánchez-Pizjuán Informasi stadionPemilikSevilla FCOperatorSevilla FCLokasiLokasi Sevilla, Andalusia, SpanyolKonstruksiDibuat1957Dibuka7 September 1958ArsitekManuel Muñoz MonasterioData teknisPermukaanRumputKapasitas45.500Ukuran lapangan105 x 68 mPemakaiSevilla FCFinal Liga Champions UEFA 1986Sunting kotak info • L • BBantuan penggunaan templat ini Stadion Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán adalah sebuah stadion sepak bola yang terletak di Sevilla, Spanyol. Stadion ini merupakan ...

Moated half-timbered manor house in Cheshire, England Little Moreton HallLittle Moreton Hall's south range, constructed in the mid-16th century. The weight of the third-storey glazed gallery, possibly added at a late stage of construction, has caused the lower floors to bow and warp. Location map and quick summary TypeManor houseLocationNear Congleton, Cheshire, EnglandCoordinates53°07′38″N 2°15′07″W / 53.1270927°N 2.2518127°W / 53.1270927; -2.2518127Builtc...

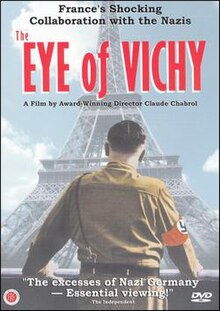

1993 French filmThe Eye of VichyDVD coverDirected byClaude ChabrolWritten byJean-Pierre AzémaRobert PaxtonProduced byJean-Pierre Ramsay-LeviNarrated byMichel BouquetBrian CoxEdited byFrédéric LossignolStéphanie LouisProductioncompaniesCanal+Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC)Délégation à la Mémoire et à l'Information HistoriqueFIT ProductionsInstitut National de l'Audiovisuel (INA)La Sofica BymagesMinistre de la Culture et de l'Éducation NationaleSecrétariat d'État aux An...

League of Ireland Cup 2017EA Sports Cup 2017 Competizione League of Ireland Cup Sport Calcio Edizione 44ª Organizzatore FAI Date dal 27 marzo 2017al 16 settembre 2017 Luogo Irlanda Partecipanti 24 Risultati Vincitore Dundalk(6º titolo) Secondo Shamrock Rovers Statistiche Incontri disputati 23 Gol segnati 56 (2,43 per incontro) Cronologia della competizione 2016 2018 Manuale La League of Ireland Cup 2017, nota anche come EA Sports Cup 2017 per ragioni di spons...

Cargo ship of the United States Navy For other ships with the same name, see USS Sappho. History United States NameUSS Sappho NamesakeThe asteroid Sappho BuilderWalsh-Kaiser Company, Providence, Rhode Island Laid down12 December 1944 Launched3 March 1945 Commissioned24 April 1945 Decommissioned23 May 1946 Stricken15 October 1946 FateSold for scrap in 1965 General characteristics Class and typeArtemis-class attack cargo ship TypeS4–SE2–BE1 Displacement 4,087 long tons (4,153 t) light ...

U.S. Senate election in West Virginia 1982 United States Senate election in West Virginia ← 1976 November 7, 1982 1988 → Nominee Robert Byrd Cleve Benedict Party Democratic Republican Popular vote 387,170 173,910 Percentage 68.49% 30.76% County resultsByrd: 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 80–90%Benedict: &...

Hair in the nostrils of adult humans Nasal hair Nasal hair or nose hair is the hair in the human nose. Adult humans have hair in the nostrils. Nasal hair functions include filtering foreign particles from entering the nasal cavity, and collecting moisture.[1] In support of the first function, the results of a 2011 study indicated that increased nasal hair density decreases the development of asthma in those who have seasonal rhinitis, possibly due to an increased capacity of the hair ...

Belgian cyclist Paul HerygersPersonal informationFull namePaul HerygersBorn (1962-11-22) 22 November 1962 (age 61)Herentals, BelgiumTeam informationCurrent teamRetiredDisciplineCyclo-crossMountain bike racingRoleRiderProfessional teams1992Saxon-Gatorade1993Saxon-Breitex1994Saxon-Selle Italia1995–1996Tönissteiner-Saxon1997Tönissteiner-Colnago1998Tönissteiner-Colnago-Saxon1999Spar-RDM Major wins Cyclo-cross World Championship (1994) Cyclo-cross Belgian Championship (1993, 19...

American politician John Piscopo is a Republican member of the Connecticut House of Representatives and is the Senior Republican Whip, the third-highest ranking leadership position within the House Republican caucus. He represents Burlington, Harwinton, Litchfield, and Thomaston.[1] He was first elected in 1988.[2] Piscopo is a board member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).[3] In October 2012, he was one of nine U.S. state legislators who went on an ...

Komando Distrik Militer 1615/Lombok TimurLambang Korem 162/Wira BhaktiNegara IndonesiaAliansiTNI Angkatan DaratTipe unitKodimPeranSatuan TeritorialBagian dariKodam IX/UdayanaMakodimSelong, Kabupaten Lombok TimurBaret H I J A U TokohKomandanLetkol Inf. Bayu Sigit Dwi UntoroKepala StafMayor Inf. Sarbini, S.E.Komando Distrik Militer 1615/Lombok Timur merupakan satuan kewilayahan yang berada dibawah komando Korem 162/Wirabakti. Kodim 1615/Lombok Timur memiliki wilayah teritorial ya...

Министерство природных ресурсов и экологии Российской Федерациисокращённо: Минприроды России Общая информация Страна Россия Юрисдикция Россия Дата создания 12 мая 2008 Предшественники Министерство природных ресурсов Российской Федерации (1996—1998)Министерство охраны...

Indigenous people of Brazil You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (December 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia. Consider adding a t...

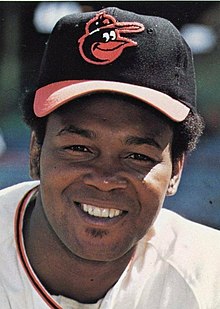

American baseball player (1942–2021) Baseball player Grant JacksonJackson in 1972PitcherBorn: (1942-09-28)September 28, 1942Fostoria, Ohio, U.S.Died: February 2, 2021(2021-02-02) (aged 78)North Strabane Township, Pennsylvania, U.S.Batted: SwitchThrew: LeftMLB debutSeptember 3, 1965, for the Philadelphia PhilliesLast MLB appearanceSeptember 8, 1982, for the Pittsburgh PiratesMLB statisticsWin–loss record86–75Earned run average3.46Strikeouts889Saves79 Te...

المعهد العالي للتجارة وإدارة المقاولات معلومات المؤسس الحسن الثاني بن محمد التأسيس 1971 النوع مدرسة عليا للتجارة الموقع الجغرافي إحداثيات 33°31′38″N 7°38′18″W / 33.5271°N 7.6382°W / 33.5271; -7.6382 المكان الدار البيضاء، المغرب البلد المغرب[1] الإدارة المدير مح...

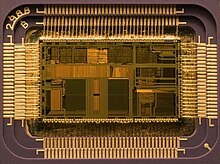

Clock-doubled i486 This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Intel DX2 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this me...

Historical city in Uttar Pradesh, India This article is about the Indian city. For H. P. Lovecraft's fictitious city, see The Doom That Came to Sarnath. Historical City in Uttar Pradesh, IndiaSarnathHistorical CityView of Sarnath, looking from the ruins of the ancient Mulagandha Kuty Vihara towards the Dhamek StupaNickname: IsipatanaSarnathShow map of IndiaSarnathShow map of Uttar PradeshCoordinates: 25°22′41″N 83°01′30″E / 25.3780°N 83.0251°E / 25.378...