Ground proximity warning system

|

Read other articles:

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Desember 2023. Javi Fuego Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Javier Fuego MartínezTanggal lahir 4 Januari 1984 (umur 40)Tempat lahir Pola de Siero, SpanyolTinggi 1,81 m (5 ft 11+1⁄2 in)Posisi bermain Gelandang bertahanInformasi klubKlub saat in...

2007 concert tour by Josh Groban This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. R...

UniMás affiliate in El Paso, Texas This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: KTFN – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) KTFNEl Paso, TexasLas Cruces, New MexicoCiudad Juárez, ChihuahuaUnited States–MexicoCityEl Paso, TexasCha...

Keuskupan MalolosDiœcesis MalolosinæDiyosesis ng Malolos Diócesis de MalolosKatolik LambangLokasiNegara FilipinaWilayahBulacan dan Kota ValenzuelaProvinsi gerejawiManilaStatistikLuas2.672 km2 (1.032 sq mi)Populasi- Total- Katolik(per 2015)3.841.2103,303,441 (87.5%)Paroki108InformasiDenominasiKatolik RomaGereja sui iurisGereja LatinRitusRitus RomaPendirian11 Maret 1962KatedralKatedral Santa Maria Bunda Tak Bercela MalolosPelindungMaria Bunda Tak Berce...

Village in Nova Scotia, CanadaSt. Peter's Gaelic: Baile PheadairVillageNickname(s): Gateway to the Bras d'OrThe Village on the CanalWhere the Ocean meets the Inland SeaSt. Peter'sLocation of St Peter'sShow map of Nova ScotiaSt. Peter'sSt. Peter's (Canada)Show map of CanadaCoordinates: 45°39′52″N 60°52′33″W / 45.664555°N 60.875744°W / 45.664555; -60.875744CountryCanadaProvinceNova ScotiaMunicipalityRichmond CountyFounded1650Government • Vil...

Upcoming Namma Metro station under Green Line Manjunatha Nagara Namma Metro stationGeneral informationLocationArch No 45, Gomatha Complex Bagalgunte, next to Bagalgunte, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560073Coordinates13°03′01″N 77°29′40″E / 13.05022°N 77.49444°E / 13.05022; 77.49444Owned byBangalore Metro Rail Corporation Ltd (BMRCL)Operated byNamma MetroLine(s)Green LinePlatformsSide platform Platform-1 → MadavaraPlatform-2 → Silk InstituteTracks2ConstructionSt...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: コルク – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2017年4月) コルクを打ち抜いて作った瓶の栓 コルク(木栓、�...

Questa voce sugli argomenti allenatori di pallacanestro statunitensi e cestisti statunitensi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti dei progetti di riferimento 1, 2. Roger Brown Brown (a destra) con la maglia degli Indiana Pacers Nazionalità Stati Uniti Altezza 196 cm Peso 93 kg Pallacanestro Ruolo Ala piccolaAllenatore Termine carriera 1978 - giocatore1986 - allenatore Hall of fame Naismith Hall of Fame (2013...

Scottish physician George BlackBorn1854EdinburghDied5 May 1913TorquayOccupation(s)Physician, writer George Black (1854 – 5 May 1913) was a Scottish physician who operated a vegetarian hotel in Belstone called Dartmoor House. Black was born in Edinburgh where he obtained his M.B. He was Medical Officer of Health to the Keswick Urban Council.[1] He worked as a medical doctor at Greta Bank on Greenway Road in Chelston, Torquay.[2] He became a vegetarian in 1896 for humanitarian...

Canadian politician This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: John Bazalgette – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Colonel John Bazalgette (15 December 1784 – 28 March 1868) was an army officer actively involved in the affairs of No...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant la politique, l’Italie et la linguistique. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Benito Mussolini en 1938. Duce est un terme italien provenant du latin dux et signifiant en français « conducteur », « guide » dans le sens politique. Benito Mussolini fut qualifié de duce dès avant la fondation du fascisme, alors qu'il était socialiste,...

Artikel atau sebagian dari artikel ini mungkin diterjemahkan dari Region Somali di en.wikipedia.org. Isinya masih belum akurat, karena bagian yang diterjemahkan masih perlu diperhalus dan disempurnakan. Jika Anda menguasai bahasa aslinya, harap pertimbangkan untuk menelusuri referensinya dan menyempurnakan terjemahan ini. Anda juga dapat ikut bergotong royong pada ProyekWiki Perbaikan Terjemahan. (Pesan ini dapat dihapus jika terjemahan dirasa sudah cukup tepat. Lihat pula: panduan penerjemah...

Process for selectively separating of hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic Diagram of a cylindrical flotation cell with camera and light used in image analysis of the froth surface. Froth flotation is a process for selectively separating hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic. This is used in mineral processing, paper recycling and waste-water treatment industries. Historically this was first used in the mining industry, where it was one of the great enabling technologies of the 20th centur...

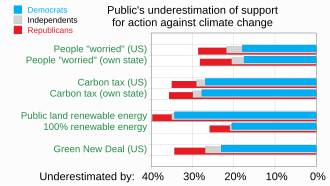

Incorrect perception of others' beliefs This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Research found that 80–90% of Americans underestimate the prevalence of support for major climate change mitigation policies and climate concern among fellow Americans. While 66–80% Americans support these policies, Americans estimate the prevalence to be 37–43%—barely ha...

Public park in Queens, New York This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: many statements look like they may have been lifted straight from cited articles (see Tweed 'magnate' typo). Please help improve this article if you can. (November 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Crocheron Park is a public park situated at 214th Street and 35th Avenue in Bayside, Queens, New York City.[1] A view from the eastern end of Croc...

Idrossido di calcio Nome IUPACdiidrossido di calcio Nomi alternativicalce spentacalce idratata Caratteristiche generaliFormula bruta o molecolareCa(OH)2 Massa molecolare (u)74,10 Aspettocristallo incolore o polvere bianca Numero CAS1305-62-0 Numero EINECS215-137-3 PubChem14777 e 6093208 SMILES[OH-].[OH-].[Ca+2] Proprietà chimico-fisicheDensità (g/cm3, in c.s.)2.24 Costante di dissociazione basica a 298 K2,3442×10−2 Solubilità in acqua1,7 g/l a 293 K[1] Costante di solubilità a ...

FC Schalke 04 IINama lengkapFußballclub Gelsenkirchen-Schalke 04 e. V.JulukanDie KönigsblauenDie KnappenBerdiri1904StadionParkstadion(Kapasitas: 5,000)Dewan EksekutifJochen SchneiderAlexander JobstPeter PetersGerald AsamoahManajerTorsten FröhlingLigaRegionalliga West2021–22ke-9, Regionalliga WestSitus webSitus web resmi klub Kostum kandang Kostum tandang FC Schalke 04 II adalah tim cadangan klub sepak bola Jerman FC Schalke 04 yang berbasis di kota Gelsenkirchen. Sejarah FC Schalke ...

Ray BrownNazionalità Stati Uniti Football americano RuoloOffensive guard Termine carriera2005 CarrieraGiovanili Arkansas State Red Wolves Squadre di club 1986-1988 St. Louis Cardinals1989-1995 Washington Redskins1996-2001 San Francisco 49ers2002-2003 Detroit Lions2004-2005 Washington Redskins Statistiche aggiornate al 1º febbraio 2014 Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Leonard Ray Brown Jr. (Marion, 4 marzo 1968) è un ex giocatore di football americ...

British psychologist (born 1934) Alan BaddeleyCBE FRSBornAlan David Baddeley (1934-03-23) 23 March 1934 (age 90)Leeds, Yorkshire, EnglandNationalityBritishEducationUniversity College LondonPrinceton UniversityUniversity of Cambridge (PhD)Known forNeuropsychological tests, Baddeley's model of working memoryAwardsCBE FRS (1993)Scientific careerInstitutionsUniversity of YorkThesisThe Influence of Acoustic and Semantic Similarity on Long-term Memory for Word Sequences (1962) Al...

Municipality in Rhineland-Palatinate, GermanyMerzalben Municipality Coat of armsLocation of Merzalben within Südwestpfalz district Merzalben Show map of GermanyMerzalben Show map of Rhineland-PalatinateCoordinates: 49°14′40″N 7°43′51″E / 49.24446°N 7.73077°E / 49.24446; 7.73077CountryGermanyStateRhineland-PalatinateDistrictSüdwestpfalz Municipal assoc.RodalbenGovernment • Mayor (2019–24) Michael Köhler[1] (CDU)Area • ...