Cittarium pica

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Fernando de la CerdaMakam Fernando de la CerdaPasanganBlanche dari PrancisAnakAlfonso de la CerdaFernando de la CerdaKeluarga bangsawanWangsa de la CerdaBapakAlfonso X dari KastiliaIbuYolanda dari AragonLahir23 Oktober 1255Meninggal1275 (usia 19 atau 20 tahun)Ciudad Real Fernando de la Cerda (1255-1275) merupakan seorang ahli waris takhta ke Mahkota Kastila sebagai putra sulung Alfonso X dan Yolanda dari Aragon. Julukannya, de la Cerda, berarti berbulu dalam bahasa spanyol, sebuah referensi b...

Arifaini Nur Dwiyanto Inspektur Komando Operasi Udara I ke-3PetahanaMulai menjabat 27 April 2023 PendahuluYudi MandegaPenggantiPetahana Informasi pribadiLahirIndonesiaAlma materAkademi Angkatan Udara (1993)Karier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan UdaraMasa dinas1993—sekarangPangkat Marsekal Pertama TNISatuanKorps PenerbangSunting kotak info • L • B Marsekal Pertama TNI Arifaini Nur Dwiyanto, M.Han. adalah seorang perwira tinggi TNI-AU yang sejak...

Bandar Udara Internasional BujumburaIATA: BJMICAO: HBBAInformasiJenisPublikLokasiBujumburaZona waktuUTC+1Koordinat{{{coordinates}}} Bandar Udara Internasional Bujumbura adalah bandar udara internasional yang terletak di kota Bujumbura, ibu kota dari Burundi dengan kode IATA BJM. Maskapai dan destinasi MaskapaiTujuan Air Burundi Entebbe, Kigali Brussels Airlines Brussels Ethiopian Airlines Addis Ababa, Entebbe Fly540 Mwanza, Nairobi Kenya Airways Nairobi-Jomo Kenyatta RwandAir Cyangugu, Kigali...

Artikel ini perlu diwikifikasi agar memenuhi standar kualitas Wikipedia. Anda dapat memberikan bantuan berupa penambahan pranala dalam, atau dengan merapikan tata letak dari artikel ini. Untuk keterangan lebih lanjut, klik [tampil] di bagian kanan. Mengganti markah HTML dengan markah wiki bila dimungkinkan. Tambahkan pranala wiki. Bila dirasa perlu, buatlah pautan ke artikel wiki lainnya dengan cara menambahkan [[ dan ]] pada kata yang bersangkutan (lihat WP:LINK untuk keterangan lebih lanjut...

Kasih di PersimpanganDitulis olehZara ZettiraSutradaraAnto ErlanggaPemeranTeuku RyanElma TheanaReynold SurbaktiDonna HarunRudy WoworJeremy ThomasPenggubah lagu temaChossy PratamaLagu pembukaApa yang Kau Rasakan? — Ulfie SyahrulNegara asalIndonesiaBahasa asliIndonesiaProduksiProduser eksekutifDhamoo PunjabiGobind PunjabiProduserRaam PunjabiRumah produksiMultivision PlusRilis asliJaringanSCTVRilis1997 (1997) Kasih di Persimpangan adalah sinetron Indonesia produksi Multivision Plus yang ...

Governmental wealth redistribution Transfer payments to (persons) as a percent of federal revenue in the United States Transfer payments to (persons + business) in the United States In macroeconomics and finance, a transfer payment (also called a government transfer or simply fiscal transfer) is a redistribution of income and wealth by means of the government making a payment, without goods or services being received in return. These payments are considered to be non-exhaustive because they d...

Swedish songwriter (1962–) This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Jörgen Elofsson – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this templat...

العلاقات الساموية الناميبية ساموا ناميبيا ساموا ناميبيا تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات الساموية الناميبية هي العلاقات الثنائية التي تجمع بين ساموا وناميبيا.[1][2][3][4][5] مقارنة بين البلدين هذه مقارنة عامة ومرجعية للدولتين: وجه المقارنة س�...

967–1916 state in the Arabian Peninsula Sharifate of Meccaشرافة مكة967–1916 Flag1695 map of the Sharifate of MeccaStatusunder Abbasid Caliphate (967–969)Fatimid Caliphate (969–1171)Zengid Sultanate (1171–1174)Ayyubid Sultanate (1174–1254)Abbasid Caliphate (Mamluk Sultanate) (1254–1517)Ottoman Caliphate (1517–1783)Emirate of Diriyah (1783–1818)Ottoman Caliphate (1818–1916)CapitalMeccaOfficial languagesArabicReligion Zaydi IslamSunni Islam (later)Sharif •...

Family of rodents This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Blesmol – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) BlesmolsTemporal range: Early Miocene–Recent PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Damaraland mole-rat Scientific classification Doma...

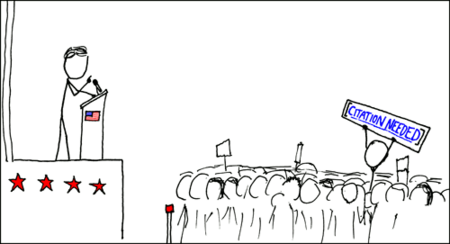

Praktik Wikipedia dalam menandai informasi yang tidak berdasar dengan peringatan butuh rujukan telah menjadi identik dengan kebutuhan akan pemeriksaan fakta secara lebih umum Komunitas editor sukarelawan Wikipedia bertanggung jawab untuk memeriksa fakta konten Wikipedia.[1] Wikipedia telah dianggap sebagai salah satu halaman web sumber terbuka (open source) gratis yang terkemuka, di mana jutaan orang dapat membaca, menyunting, dan mengirim pandangan mereka secara gratis. Hal ini dapat...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (novembre 2012). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? ...

Questa voce sull'argomento canoisti ungheresi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Danuta Kozák Nazionalità Ungheria Altezza 167 cm Peso 60 kg Canoa/kayak Specialità K1, K2, K4 Palmarès Competizione Ori Argenti Bronzi Giochi olimpici 6 1 1 Mondiali 14 2 2 Europei 16 7 0 Giochi europei 3 3 1 Per maggiori dettagli vedi qui Statistiche aggiornate al 25 agosto 2019 Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manuale Danuta Kozák (Budapest,...

Helmuth Brückner(1934)Gauleiter of Gau SilesiaIn office15 March 1925 – 4 December 1934Succeeded byJosef WagnerOberpräsident of Lower SilesiaIn office25 March 1933 – 12 December 1934Succeeded byJosef WagnerOberpräsident of Upper SilesiaIn office29 May 1933 – 12 December 1934Succeeded byJosef Wagner Personal detailsBorn(1896-05-07)7 May 1896Peilau, PrussiaDied12 January 1951(1951-01-12) (aged 54)Tayshet, USSREducationHistory, geography, philosophy and ec...

القوات المسلحة للبوسنة والهرسك شعار القوات المسلحة للبوسنة والهرسكشعار القوات المسلحة للبوسنة والهرسك الدولة البوسنة والهرسك التأسيس 1 ديسمبر 2005 الاسم الأصلي Oružane snage Bosne i Hercegovine الفروع القوات البريةالقوات الجوية المقر سراييفو القيادة الوزير مارينا بينديس[1] �...

这是马来族人名,“尤索夫”是父名,不是姓氏,提及此人时应以其自身的名“法迪拉”为主。 尊敬的拿督斯里哈芝法迪拉·尤索夫Fadillah bin Haji YusofSSAP DGSM PGBK 国会议员 副首相 第14任马来西亚副首相现任就任日期2022年12月3日与阿末扎希同时在任君主最高元首苏丹阿都拉陛下最高元首苏丹依布拉欣·依斯迈陛下首相安华·依布拉欣前任依斯迈沙比里 马来西亚能源转型与�...

Katedral PondicherryKatedral Perawan Maria Tak BernodaTamil: தூய அமலோற்பவ அன்னை பேராலயம்Katedral PondicherryKatedral PondicherryImmaculate Conception Cathedral, PondicherryKoordinat: 11°55′59″N 79°49′50″E / 11.93299°N 79.83055°E / 11.93299; 79.83055LokasiPondicherry, PuducherryNegaraIndiaDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaSejarahNama sebelumnyaGereja Santo PaulusOtorisasi bulla kepausan1692PendiriYesuitDedikasiM...

Ganja trolleybus systemOperationLocaleGanja, AzerbaijanOpen1 May 1955 (1955-05-01)Close2004 (2004)StatusClosedLines8 (max)StatisticsRoute length112.9 km (70.2 mi) (max) The Ganja trolleybus system was a system of trolleybuses forming part of the public transport arrangements in Ganja, the second most populous city in Azerbaijan, for most of the second half of the 20th century.[1] History The system was opened on 1 May 1955. At its height, it consisted of ...

Jay LethalLethal pada November 2016Nama lahirJamar ShipmanLahir29 April 1985 (umur 39)Elizabeth, New Jersey, A.S.Karier gulat profesionalNama ringBlack MachismoHydro[1]Jamar Cunningham[1]Jay Lethal[1]J.R. Lethal[2]RPM[3]El Lethál[4]Tinggi5 ft 10 in (1,78 m)[5][6]Berat223 pon (101 kg)[7]Asal dariElizabeth, New Jersey[5][6][7]Dilatih olehDan Maff[1]Jersey All Pr...

American author and politician (1903–1987) For the Broadway and movie actress, see Claire Luce. Clare Boothe LuceUnited States Ambassador to Italy In officeMay 4, 1953 – December 27, 1956PresidentDwight D. EisenhowerPreceded byEllsworth BunkerSucceeded byJames David ZellerbachMember of the U.S. House of Representativesfrom Connecticut's 4th districtIn officeJanuary 3, 1943 – January 3, 1947Preceded byLe Roy D. DownsSucceeded byJohn Lodge Personal detailsBor...