Cerulean

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Heads of state of India For historical heads of state in the Indian Subcontinent, see List of Indian monarchs. This article is part of a series on the Politics of India Constitution and law Constitution of India Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles and Fundamental Duties of India Human rights Judicial review Taxation Uniform Civil Code Basic structure doctrine Amendment Law of India Indian criminal law Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam ...

4th edition of the Miss Grand Japan beauty pageant Miss Grand Japan 2018DateJuly 30, 2018VenueWOMB Club, Shibuya, TokyoEntrants15Placements5WinnerHaruka Oda (Saitama)CongenialityHonami Nishikawa (Chiba)Best in SwimsuitMariko Nakagawa (Chiba)← 20172019 → Miss Grand Japan 2018 (Japanese: 2018 ミス・グランド・ジャパン) was the 4th edition of the Miss Grand Japan pageant, held on July 30, 2018,[1][2][3] at the WOMB Club, Shibuya, Tokyo. ...

Beata PoźniakBeata Poźniak pada 2013LahirBeata Poźniak30 April 1960 (umur 63)Gdańsk, PolandiaPekerjaanPemeran, sutradara, produser, penulis, seniman, aktivisAnak1PenghargaanEarphones Award Beata Poźniak (pengucapan bahasa Polandia: [bɛˈat̪a pɔʑˈɲak]; lahir 30 April 1960) adalah seorang aktris, sutradara, penyair, pelukis dan narator pemenang Earphones Award asal Polandia. Ia juga merupakan aktivis HAM yang mendorong pengakuan resmi Hari Wanita Internasional di Amerika S...

William John BankesFRSPotret William John Bankes, karya George Sandars tahun 1812 Anggota Parlemendapil TruroMasa jabatan1810–1810 PendahuluCharles Powlett, Baron Bayning KeduaPenggantiSir George Warrender, Baronet KeempatAnggota Parlemendapil Universitas Cambridge (Parlemen)Masa jabatan1822–1826 PendahuluJohn Henry SmythPenggantiJohn Copley, Baron Lyndhurst PertamaAnggota Parlemendapil MarlboroughMasa jabatan1829–1832 PendahuluJames Brudenell, Earl Cardigan KetujuhPenggantiHenry Bingha...

Ashish NandaDirector Indian Institute of Management, AhmedabadIn officeSeptember 2013 – April 2017 Personal detailsNationalityAmericanAlma materIndian Institute of Technology DelhiIndian Institute of Management AhmedabadHarvard UniversityOccupationProfessor Ashish Nanda is a business economist and professor who is the former Director of the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIMA).[1] Nanda joined IIMA as Director on 2 Sept 2013.[2] Upon taking charge, Nanda...

تحتاج هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر إضافية لتحسين وثوقيتها. فضلاً ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة بإضافة استشهادات من مصادر موثوق بها. من الممكن التشكيك بالمعلومات غير المنسوبة إلى مصدر وإزالتها. بحاجة للاستشهاد بمعجم مطبوع بدلاً عن قاعدة بيانات معجمية على الإنترنت. جزء من س...

ESteemENT.co.LtdNama asli에스팀 엔터테인먼트IndustriFashion, Model ManagementDidirikan2003KantorpusatB-404 RodeoStar B/D, 46-gil, Apgujeong-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, KoreaTokohkunciKim So Yeon (CEO)Situs webESteem ESteem Entertainment (Korean: 에스 팀 엔터테인먼트) Pada tahun 2003, Esteem adalah agensi model terkenal di korea yang menciptakan model ESteem yang muncul sebagai perusahaan produksi mode mode dan manajemen model dengan kolaborasi model dan pakar terhormat di industr...

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento competizioni calcistiche non è ancora formattata secondo gli standard. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. Pro League 2008-2009Jupiler Pro League 2008-2009 Competizione Pro League Sport Calcio Edizione 106ª Organizzatore URBSFA/KBVB Date dal 16 agosto 2008al 16 maggio 2009 Luogo Belgio Partecipanti 18 Risultati Vincitore Standard Liegi(10º titolo) Ret...

土库曼斯坦总统土库曼斯坦国徽土库曼斯坦总统旗現任谢尔达尔·别尔德穆哈梅多夫自2022年3月19日官邸阿什哈巴德总统府(Oguzkhan Presidential Palace)機關所在地阿什哈巴德任命者直接选举任期7年,可连选连任首任萨帕尔穆拉特·尼亚佐夫设立1991年10月27日 土库曼斯坦土库曼斯坦政府与政治 国家政府 土库曼斯坦宪法 国旗 国徽 国歌 立法機關(英语:National Council of Turkmenistan) ...

Si ce bandeau n'est plus pertinent, retirez-le. Cliquez ici pour en savoir plus. Cet article ne cite pas suffisamment ses sources (août 2012). Si vous disposez d'ouvrages ou d'articles de référence ou si vous connaissez des sites web de qualité traitant du thème abordé ici, merci de compléter l'article en donnant les références utiles à sa vérifiabilité et en les liant à la section « Notes et références ». En pratique : Quelles sources sont attendues ? Com...

American jockey (1867–1925) Fred TaralFred Taral around 1903OccupationJockey & trainerBornAugust 2, 1867Peoria, Illinois, United StatesDiedFebruary 13, 1925 (aged 57)Jamaica, New York, USCareer wins1,437Major racing winsUnited States wins:September Stakes (1890)Dolphin Stakes (1891, 1893)Double Event Stakes (part 2)(1891, 1892, 1899)Juvenile Stakes (1891)Ladies Handicap (1891, 1897)Reapers Stakes (1891, 1896, 1898)Sapphire Stakes (1891)Spring Stakes (1891, 1896, 1897)Flight Stakes (1892...

Filtration of fluids through porous materials For the mathematical and statistical physics term, see percolation theory. In coffee percolation, soluble compounds leave the coffee grounds and join the water to form coffee. Insoluble compounds (and granulates) remain within the coffee filter. Percolation in a square lattice. In physics, chemistry, and materials science, percolation (from Latin percolare 'to filter, trickle through') refers to the movement and filtering of fluids t...

Royal dukedom in the United Kingdom This article is about the title. For its current holder, see Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex. For the pub in London, see Duke of Sussex, Acton Green. Dukedom of SussexCreation date19 May 2018 (announced)[1]16 July 2018 (Letters Patent)[2]CreationSecondCreated byElizabeth IIPeeragePeerage of the United KingdomFirst holderPrince Augustus FrederickPresent holderPrince HarryHeir apparentPrince Archie of SussexRemainder tothe 1st Duke's heirs male o...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (نوفمبر 2018) سيمون سيمون معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة (بالفرنسية: Simone Thérèse Fernande Simon) الميلاد 23 أبريل 1911 مارسيليا الوفاة 22 فبراير 2005 (93 سنة) الدائرة الثامن...

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع تصفيات كأس العالم 1998 (توضيح). تصفيات كأس العالم لكرة القدم 1998تفاصيل المسابقةالفرق174إحصائيات المسابقةالمباريات الملعوبة643الأهداف المسجلة1٬922 (2٫99 لكل مباراة)→ 1994 2002 ← منتخبات تأهلت لكاس العالم منتخبات فشلت في التأهل منتخبا�...

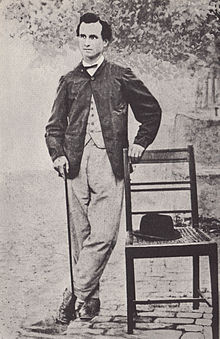

Ancient Chinese divination text The Book of Changes redirects here. For other uses, see The Book of Changes (disambiguation). For other uses of I Ching or Yijing, see I Ching (disambiguation) and Yijing (disambiguation). I Ching Title page of a Song dynasty (c. 1100) edition of the I ChingOriginal title易LanguageOld ChineseSubjectDivination, cosmologyPublishedLate 9th century BCPublication placeChinaOriginal text易 at Chinese Wikisource I ChingI (Ching) in seal script (top),[...

Afrikaans clergyman, founder of the First Afrikaans Language Movement (1847–1911) You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Afrikaans. (March 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated ...

奈良県出身の人物一覧(ならけんしゅっしんのじんぶついちらん)は、Wikipedia日本語版に記事が存在する奈良県出身の人物の一覧である。 公人 政治家 現職 石田昌宏(自由民主党の参議院議員):大和郡山市 稲村和美(兵庫県尼崎市長):奈良市 熊谷俊人(千葉県知事):天理市 小林茂樹(自由民主党の衆議院議員) : 奈良市 佐藤啓(自由民主党の参議院議員)...

Town in Tigray Region, Ethiopia Not to be confused with Humira. Town in Tigray, EthiopiaHumera ሑመራTownHumeraLocation within EthiopiaShow map of EthiopiaHumeraLocation within the Horn of AfricaShow map of Horn of AfricaHumeraLocation within AfricaShow map of AfricaCoordinates: 14°17′10″N 36°36′35″E / 14.28611°N 36.60972°E / 14.28611; 36.60972Country EthiopiaRegion TigrayZoneWesternWoredaKafta HumeraElevation585 m (1,919 ft)Populatio...

France Données clés Couleurs bleu et blanc Uniformes modifier L'équipe de France de baseball féminin représente la Fédération française de baseball et softball lors des compétitions internationales comme la Coupe du monde et le Championnat d'Europe. Histoire La Fédération française de baseball et softball organise des détections en janvier[1] et en mai 2019[2] dans l'optique de créer une équipe féminine de baseball pouvant participer au Championnat d'Europe de baseball fémin...