Ceolfrith

| |||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Umbu Wulang Landu ParanggiLahir(1943-08-10)10 Agustus 1943Kananggar, Paberiwai, Sumba TimurMeninggal6 April 2021(2021-04-06) (umur 77)Sanur, BaliKebangsaanIndonesiaDikenal atasSastrawanSuami/istriRambu Hana Hunggu Ndami (meninggal - 2003)AnakUmbu Domu Wulang Maramba Andang Rambu Anarara Wulang Paranggi Umbu Wulang Tanaamahu Paranggi Umbu Wulang Landu Paranggi (10 Agustus 1943 – 6 April 2021) adalah seniman Indonesia berasal dari Sumba yang sering disebut sebagai tokoh mi...

Jalur kereta api Sumari–Gresik–KandanganIkhtisarJenisJalur lintas cabangSistemJalur kereta api rel ringanStatus Beroperasi Kandangan - Indro Tidak Beroperasi Indro - Sumari LokasiJawa TimurTerminusSumariKandanganOperasiDibangun olehNederlandsch-Indische Spoorweg MaatschappijDibuka1 Juni 1902, segmen Sumari–Gresik3 Januari 1924, segmen Kandangan–GresikDitutup1943, segmen Sumari–Gresik1982, segmen Indro–GresikPemilikPT Kereta Api IndonesiaOperator Daerah Operasi VIII Surabaya KAI Co...

Artikel ini bukan mengenai Bahasa Miji. Cari artikel bahasa Cari berdasarkan kode ISO 639 (Uji coba) Kolom pencarian ini hanya didukung oleh beberapa antarmuka Halaman bahasa acak Bahasa Kaman Miju, Kùmán Geman, Kman Pengucapan[kɯ˧˩mɑn˧˥]WilayahArunachal Pradesh, IndiaEtnisMiju MishmiPenutur18 (2006)[1] Rumpun bahasakemungkinan Sino-Tibetan (Midzuish), atau bahasa yang terisolasi Kaman Kode bahasaISO 639-3mxjGlottologmiju1243[2] Status konservasi Punah...

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Harian SinggalangMembina Harga Diri untuk Kesejahteraan Nusa dan Bangsa Kantor pusat di PadangTipeSurat kabar harian independenFormatKoranPenerbitPT Genta Singgalang PressPemimpin redaksiKhairul JasmiDidirikan18 Desember 1968PusatPadangSitus webwww.hariansinggalang.co.id Harian Singgalang adalah sebuah surat kabar hari...

Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Washington Square Park (disambiguasi). Washington Square ParkJenisMunisipalKoordinat40°43′51″N 73°59′51″W / 40.73083°N 73.99750°W / 40.73083; -73.99750Koordinat: 40°43′51″N 73°59′51″W / 40.73083°N 73.99750°W / 40.73083; -73.99750Dibuka1871Dioperasikan olehDepartemen Taman dan Rekreasi New York CityStatusTerbuka Washington Square Park adalah salah satu taman paling terkenal di antara 1.900 t...

العلاقات المكسيكية الكندية كندا المكسيك تعديل مصدري - تعديل العلاقات المكسيكية الكندية هي العلاقات التي تجمع بين كندا والولايات المتحدة المكسيكية. تغيرت العلاقات بين المكسيك وكندا بشكل إيجابي في السنوات الأخيرة، وذلك على الرغم من خمول العلاقات التاريخي...

Voce principale: Carrarese Calcio 1908. Carrarese Calcio 1908Stagione 1989-1990Sport calcio Squadra Carrarese Allenatore Giuseppe Savoldi Presidente Luciano Grassi e Menotti Gaspari Serie C16º posto nel girone A. Maggiori presenzeCampionato: Pistella (34) Miglior marcatoreCampionato: Pistella (8) 1988-1989 1990-1991 Si invita a seguire il modello di voce Questa voce raccoglie le informazioni riguardanti la Carrarese Calcio 1908 nelle competizioni ufficiali della stagione 1989-1990. Ind...

The 2000–01 OHL season was the 21st season of the Ontario Hockey League. The Guelph Storm moved from the Guelph Memorial Gardens to the Guelph Sports and Entertainment Centre at the start of the season. The Owen Sound Platers were renamed to the Owen Sound Attack Twenty teams each played 68 games. The Ottawa 67's won the J. Ross Robertson Cup, defeating the Plymouth Whalers. Teams 2000-01 Ontario Hockey League Eastern Conference Division Team City Arena East Belleville Bulls Belleville, Ont...

Seite zur Hauptstraße Rückseite des Hauses Das Haus Hauptstraße 28 in Gundelfingen an der Donau, einer Stadt im schwäbischen Landkreis Dillingen an der Donau in Bayern, wurde im 17. Jahrhundert errichtet. Das Gebäude ist ein geschütztes Baudenkmal. Architektur Das zweigeschossige Giebelhaus mit einem modernen Ladenlokal im Erdgeschoss besitzt Profilgesimse als Geschosstrennung. Der seitlich mit S-Stufen begrenzte Giebel wird vertikal durch Lisenen in fünf Zonen geteilt, diese ende...

Jatidjan Menteri Maritim Indonesia ke-2Masa jabatan25 Juli 1966 – 17 Oktober 1967PresidenSoekarnoSoehartoPendahuluAli SadikinPenggantiIndroyono Soesilo (2014)Menteri Perhubungan Indonesia ke-19Masa jabatan28 Maret 1966 – 25 Juli 1966PresidenSoekarnoPendahuluAli SadikinPenggantiSutopo Informasi pribadiLahir(1926-11-27)27 November 1926Gombong, Kebumen, Jawa Tengah, Hindia BelandaMeninggal12 Januari 2008(2008-01-12) (umur 81)[1]Jakarta, IndonesiaKebangs...

هذه المقالة تحتاج للمزيد من الوصلات للمقالات الأخرى للمساعدة في ترابط مقالات الموسوعة. فضلًا ساعد في تحسين هذه المقالة بإضافة وصلات إلى المقالات المتعلقة بها الموجودة في النص الحالي. (ديسمبر 2018) وحدات التخزين الضوئية: تعتبر وحدات التخزين الضوئية من أحدث وسائط التخزين المس...

British historian (born 1939) For those of a similar name, see Norman Davis (disambiguation). Norman DaviesCMG, FBA, FRHistSDavies in 2018BornIvor Norman Richard Davies (1939-06-08) 8 June 1939 (age 84)Bolton, Lancashire, EnglandCitizenshipBritishPolishSpouses Maria Zielińska (m. 1966)[1] Maria Korzeniewicz (m. 1984)Children2RelativesDonny Davies (uncle)Academic backgroundEducationMagdalen College, Oxford (BA)Universi...

Planned but never-built Roman Catholic cathedral in Queensland, Australia Holy Name CathedralHoly Name Cathedral, original design of 1925General informationTypeCathedral (never completed)Architectural styleEnglish BaroqueAddressGotha and Gipps, Ann and Wickham Streets, Fortitude Valley, QueenslandCountryAustraliaCoordinates27°27′35″S 153°01′58″E / 27.4596°S 153.0327°E / -27.4596; 153.0327 (Holy Name Cathedral (never completed))Construction started14...

Fuerza Marítima de Autodefensa de Japón 海上自衛隊(Kaijō Jieitai) Enseña naval japonesa.Activa 1 de julio de 1954 (69 años)País Japón JapónRama/s ArmadaTipo rama militararmadaTamaño 50 800 personas 254 barcos 346 aeronavesParte de Fuerzas de Autodefensa de JapónAcuartelamiento Ichigaya, TokioAlto mandoComandante en jefe (Primer ministro) Fumio KishidaMinistro de Defensa Minoru KiharaJefe del Estado Mayor Conjunto General Yoshihide YoshidaJefe del Estado Mayor de ...

习近平 习近平自2012年出任中共中央总书记成为最高领导人期间,因其废除国家主席任期限制、开启总书记第三任期、集权统治、公共政策与理念、知识水平和自述经历等争议,被中国大陸及其他地区的民众以其争议事件、个人特征及姓名谐音创作负面称呼,用以恶搞、讽刺或批评习近平。对习近平的相关负面称呼在互联网上已经形成了一种活跃、独特的辱包亚文化。 权力�...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Matariyyah – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Al-Matariyyah or Matariye, Mataria (Arabic: المطرية), is a village in South Lebanon near the Litani river. vte Sidon District, South GovernorateCapitalSidonTow...

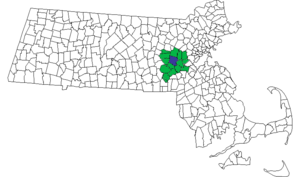

Bus and paratransit service in Massachusetts MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA)Map of the MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA) service area in green with the central hub town of Framingham in blue.Founded2006HeadquartersFramingham, Massachusetts, USLocaleMetroWest, MassachusettsService area Ashland Dover Framingham Holliston Hopedale Hopkinton Hudson Marlborough Milford Natick Sherborn Southborough Sudbury Wayland Wellesley Weston Service type Bus paratransit Alliance495/Met...

1971 studio album by Joni MitchellBlueStudio album by Joni MitchellReleasedJune 22, 1971 (1971-06-22)Recorded1971StudioA&M, Hollywood, CaliforniaGenre Folk folk rock Length36:15LabelRepriseProducerJoni MitchellJoni Mitchell chronology Ladies of the Canyon(1970) Blue(1971) For the Roses(1972) Singles from Blue CareyReleased: August 1971 CaliforniaReleased: October 1971 Blue is the fourth studio album by Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, released on June 22, ...

此條目介紹的是中国铁路的呼和浩特站。关于属于呼和浩特地铁系统的车站,请见「呼和浩特站 (地铁)」。 此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2017年7月20日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的标题(来源搜索:呼和浩特站 — 网页、新闻、书籍、学术、图像),以检查网络上是否存在...

2007 single by DJ Khaled featuring T-Pain, Trick Daddy, Rick Ross and Plies This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.Find sources: I'm So Hood – news · newspapers ·...